Helepolis

Helepolis (Greek: ἑλέπολις, English: "Taker of Cities") is the Greek name for a movable siege tower.

| Helepolis (Taker of Cities) | |

|---|---|

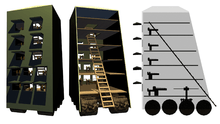

A Helepolis-like Siege Engine showing catapults, stairs and movement capstan. | |

| Type | Siege engine |

| Place of origin | Ancient Greece |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Polyidus of Thessaly |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 160 tons |

| Width | 65 ft (20 m) |

| Height | 130 ft (40 m) |

| Crew | 3400 |

| Armor | Iron plates |

Main armament | 2× 180 lb (82 kg) catapults 4× 60 lb (27 kg) catapults 10× 30 lb (14 kg) catapults |

Secondary armament | 4× dart throwers |

The most famous was that invented by Polyidus of Thessaly, and improved by Demetrius I of Macedon and Epimachus of Athens, for the Siege of Rhodes (305 BC). Descriptions of it were written by Diodorus Siculus,[1] Vitruvius, Plutarch, and in the Athenaeus Mechanicus.

Description

.jpg)

The Helepolis was essentially a large tapered tower, with each side about 130 feet (41.1 m) high, and 65 feet (20.6 m) wide that was manually pushed into battle. It rested on eight wheels, each 15 feet (4.6 m) high and also had casters, to allow lateral movement as well as direct. The three exposed sides were rendered fireproof with iron plates, and stories divided the interior, connected by two broad flights of stairs, one for ascent and one for descent. The machine weighed 160 tons, and required 3,400 men working in relays to move it, 200 turning a large capstan driving the wheels via a belt, and the rest pushing from behind. The casters permitted lateral movement, so the entire apparatus could be steered towards the desired attack point, while always keeping the siege engines inside aimed at the walls, and the protective body of the machine directly between the city walls and the men pushing behind it.

The Helepolis bore a fearsome complement of heavy armaments, with two 180-pound (82 kg) catapults, and one 60-pounder (27 kg) (classified by the weight of the projectiles they threw) on the first floor, three 60-pounders (27 kg) on the second, and two 30-pounders (14 kg) on each of the next five floors. Apertures, shielded by mechanically adjustable shutters, lined with skins stuffed with wool and seaweed to render them fireproof, perforated the forward wall of the tower for firing the missile weapons. On each of the top two floors, soldiers could use two light dart throwers to easily clear the walls of defenders.

Siege of Rhodes

As the Helepolis was pushed towards the city, the Rhodians managed to dislodge some of the metal plates, and Demetrius ordered it withdrawn from battle to protect it from being burned. Following the failure of the siege, the Helepolis along with the other siege engines were abandoned, and the people of Rhodes melted down their metal plating and sold abandoned weapons, using the materials and money to build a statue of their patron god, Helios, the Colossus of Rhodes, known as one of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World.

Vitruvius offers an alternative version, in which the Rhodians begged Diognetus, once the town architect of Rhodes, to find a way to capture the Helepolis. By cover of night he had the Rhodians knock a hole through the wall and channel large amounts of water, mud and sewage onto the area where the Helepolis was expected to attack the following day. Diognetus was successful; the tower was brought forth to the anticipated attack position and became irretrievably stuck in the mire. Once the siege was lifted, the Rhodians sold Demetrius' abandoned engines and used the money to erect the enormous Colossus of Rhodes.

Later usage

Demetrius used a similar machine again in 292 BC against the Thebans in the siege of Thebes and captured the city the next year.

(In subsequent ages, siege engineers continued to use the name helepolis for moving towers which carried battering rams, as well as machines for throwing spears and heavy stones. The Byzantines much later used the term helepolis to describe a very different siege engine; the traction trebuchet. The first recorded use of this usage, was by Theophylact Simocatta in describing the siege of Tiflis in the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628.[2]

References

- Diodorus Siculus, Book 20. 48 online.

- Dennis 1998, pp. 103–104

- Connolly, Peter. Greece and Rome at War. London: Greenhill Books, 1998.

- Warry, John. Warfare in the Classical World. Salamanda Books.

- Campbell, Duncan B. Greek and Roman Siege Machinery 399 BC-AD 363. Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-605-4

External links

- Dennis, George T. (1998). "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: The Helepolis". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies v.39. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- Helepolis at LacusCurtius

- Ancient Greek war machines: The Helepolis, a fortified wheeled tower