Healthcare in Peru

Peru has a decentralized healthcare system that consists of a combination of governmental and non-governmental coverage. Five sectors administer healthcare in Peru today: the Ministry of Health (60% of population), EsSalud (30% of population), and the Armed Forces (FFAA), National Police (PNP), and the private sector (10% of population).[1]

.jpg)

History

In 2009, the Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA) passed a Universal Health Insurance Law in an effort to achieve universal health coverage. The law introduces a mandatory health insurance system as well, automatically registering everyone, regardless of age, who living in extreme poverty under Integral Health Insurance (Seguro Integral de Salud, SIS).[2] As a result, coverage has increased to over 80% of the Peruvian population having some form of health insurance.[2] Health workers and access to healthcare continue to be concentrated in cities and coastal regions, with many areas of the country having few to no medical resources. However, the country has seen success in distributing and keeping health workers in more rural and remote regions through a decentralized human resources for health (HRH) retention plan.[3] This plan, also known as SERUMS, involves having every Peruvian medical graduate spend a year as a primary care physician in a region or pueblo lacking medical providers, after which they go on to specialize in their own profession.[4]

Healthcare policy struggles

In the years since the collapse of the Peruvian health sector in the 1980s and 1990s that was the result of hyperinflation and terrorism, healthcare in Peru has made great strides. Victories include an increase in spending; more health services and primary care clinics; a sharp spike in the utilization of health services, especially in rural areas; an improvement in treatment outcomes, and a decrease in infant mortality and child malnutrition. However, serious issues still exist.

Reducing the gap between the health status of the poor and non-poor

Despite measures that have been taken to reduce disparities between middle-income and poor citizens, vast differences still exist. The infant mortality rates in Peru remain high considering its level of income. These rates go up significantly when discussing the poor. In general, Peru’s poorest citizens are subject to unhealthy environmental conditions, decreased access to health services, and typically have lower levels of education. Because of environmental issues such as poor sanitation and vector infestation, higher occurrences of communicable diseases are usually seen among such citizens.[5] Additionally, there is a highly apparent contrast between maternal health in rural (poor) versus urban environments. In rural areas, it was found that less than half of women had skilled attendants with them during delivery, compared to nearly 90% of urban women. According to a 2007 report, 36.1% of women in the poorest sector gave birth within a healthcare facility, compared to 98.4% of those in the richest sector. Peru's relatively high maternal mortality can be attributed to disparities such as these.[6] In addition to allocating less of its GDP to health care than its Latin American counterparts, Peru also demonstrates inequalities in the amount of resources that are set aside for poor and non-poor citizens. The richest 20% of the population consume approximately 4.5 times the amount of health good and services per capita than the poorest 20%.[5]

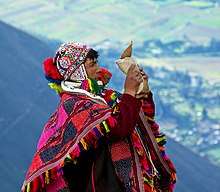

Traditional and indigenous medicine

As of 2006, approximately 47% of the Peruvian population is considered indigenous.[7] Many indigenous people continue to carry out medical practices utilized by their ancestors, which makes the Peruvian medical system very interesting and unique. In many parts of the country, shamans (also known as curanderos) help to maintain the balance between body and soul. It is a commonly held belief that when this relationship is disturbed, illness will result. Common illnesses experienced by the indigenous population of Peru include susto (fright sickness), hap’iqasqa (being grabbed by the earth), machu wayra (an evil wind or ancestor sickness), uraña (illness caused by the wind or walking soul), colds, bronchitis, and tuberculosis. To treat many of these maladies, indigenous communities rely on a mix of traditional and modern medicine.[6]

Intersection of traditional and modern medicine

Shamanism is still an important part of medical care in Peru, with curanderos, traditional healers, serving local communities, often free of charge.[8] One important aspect of Peruvian Amazon's curanderos is their use of ayahuasca, a brew with a long ceremonial history, traditionally used by the shaman to help in his/her healing work. With the introduction of Western medicine to many areas in Peru, however, interest in undergoing the training to become a curandero is diminishing, and shamans are innovating new avenues to use ayahuasca. Young individuals have increasingly been using the popular interest of tourists in the brew and its psychotherapeutic properties as a reason to undergo the training to become a curandero and continue the traditions.[9]

Curanderos, medicinal plants, and traditional medicine still have a place in the Peruvian healthcare system, even as biomedicine (Western Medicine) is made available and affordable for all, including rural communities. In fact, it's been seen that the continued use of traditional medical treatments is independent of access or affordability of biomedical care, in Peru and in many other indigenous regions in Latin America.[10][11][12] There is a strong reliance on medicinal plant use within households, especially as a first response to a health emergency.[10][11] Many households maintain a strong base of knowledge of medicinal plants, valuing independence in being able to address health emergencies, though the emphasis on maintaining this store of knowledge is decreasing.[13][11] Studies show that Peruvian households, like ones in the Andean region near Pitumarca, and ones in the shantytown of El Porvenir near Trujillo, still prefer herbal treatments to the use of pharmaceuticals, particularly for specific cultural, or psychosocial illnesses.[10][11] Though some preferred pharmaceuticals to household herbal solutions, because they are more effective, prescribed by doctors, and backed scientific research,[11] others had many reasons for preferring traditional solutions. Reasons included a view that medicinal plants are more natural and healthy, are less expensive, and are able to treat cultural and regional illnesses outside the scope of biomedicine.[10][11] One study also pointed to continued reliance on medicinal plants as a form of "cultural resistance"; despite biomedicine's domination over indigenous health systems, local communities use both in conjunction and perceive local remedies as both effective and a representation of cultural identity.[10] With the emergence of biomedicine in these communities, they saw a valorization of traditional and local remedies as a response.[10] In other instances, for example with childbirth, the government has played a larger role in pushing biomedical and technological services. This is in part due to development efforts and population politics, but these measures have been resisted, accepted, and modified by indigenous women.[14][15]

However, many Peruvians exercise "medical pluralism" in their health-seeking behavior, employing a combination of different health systems.[10] For example, some women encouraged and coerced into going to the medical clinic for childbirth took the pharmaceutical pills prescribed with medicinal herbal tea.[11] Western medicine and traditional medicine are not viewed as mutually exclusive, and instead are used complementarily, with households' often passing judgement on treatment they think will be most effective with each medical emergency.[10]

Quality of health in indigenous communities

Indigenous populations in Peru generally face worse health risks than other populations in the country. One source of this issue is access to health facilities. Health facilities are often a large distance away from indigenous communities and are difficult to access. Many indigenous communities within Peru are located in areas that have little land transportation. This hinders the indigenous population's ability to access care facilities. Distance along with financial constraints act as deterrents from seeking medical help. Furthermore, the Peruvian government has yet to devote significant amounts of resources to improving the quality and access to care in rural areas.[16]

There is some debated as to whether traditional medicine is a factor in the quality of health in indigenous populations. The indigenous groups of the Peruvian Amazon practice traditional medicine and healing at an especially high rate; Traditional medicine is more affordable and accessible than other alternatives[17] and has cultural significance. It has been argued that the use of traditional medicine may keep indigenous populations from seeking help for diseases such as tuberculosis[18], however this has been disproven. While some indigenous individuals choose to practice traditional medicine before seeking help from a medical professional, this number is negligible and the use of traditional medicine does not seem to prevent indigenous groups seeking medical attention.[19]

Government role and spending

Peru’s health system is divided into several key sectors: The Ministry of Health of Peru (Ministerio de Salud, or MINSA), EsSALUD (Seguro Social de Salud), smaller public programs, a large public sector, and several NGOs.[5]

Infrastructure

In 2014, the National Registry of Health Establishments and Medical Services (Registro Nacional de Establecimientos de Salud y Servicios Medicos de Apoyo - RENAES) indicated there were 1,078 hospitals in the country. Hospitals pertain to one of 13 dependencies, the most important of which are Regional Governments (450 hospitals, 42% of the total), EsSalud (97 hospitals, 9% of the total), MINSA (54 hospitals, 5% of the total) and the Private Sector (413 hospitals, 38% of the total).

Lima, the capital city, accounts for 23% of the country's hospitals (250 hospitals).[20][21]

MINSA

According to its website, the mission of the Ministry of Health of Peru (MINSA) is to “protect the personal dignity, promote health, prevent disease and ensure comprehensive health care for all inhabitants of the country, and propose and lead health care policy guidelines in consultation with all public and social actors.”[22] To carry out its goals, MINSA is funded by tax revenues, external loans, and user fees. MINSA provides the bulk of Peru’s primary health care services, especially for the poor. In 2004, MINSA recorded 57 million visits, or about 80% of public sector health care.[23] MINSA offers a type of health insurance called Seguro Integral de Salud which is free to Peruvian citizens. [24]

EsSALUD

EsSalud is Peru’s equivalent of a social security program, and it is funded by payroll taxes paid by the employers of sector workers.[5] It arose after there was pressure during the 1920s for some kind of system that would protect the increasing number of union workers. In 1935, the Peruvian government took measures to study the social security systems of Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Following the study, EsSalud was formed in Peru.[25] Because private insurance covers just a tiny percentage of the citizens, programs such as MINSA and EsSALUD are crucial for Peruvians. EsSalud, however, is not completely free to Peruvian citizens, unlike Seguro Integral de Salud, which offers free basic healthcare. The cost of EsSalud is much cheaper than private healthcare options.[26]

Role of non-governmental organizations

NGOs began appearing in Peru in the 1960s, and have steadily increased since then. The end of the violence associated with the Shining Path movement accelerated the growth of NGOs in Peru.[27] Prevalent NGOs in Peru today include USAID, Doctors without Borders, Partners in Health, UNICEF, CARE, and AIDESEP. Such programs work with MINSA to improve infrastructure and make changes to health practices and insurance programs. Many organizations also work on the frontlines of healthcare, providing medication (including contraceptives and vitamins), education, and support to Peruvians, especially in poor or less accessible areas where the need is greatest. Such programs have helped the Peruvian government combat diseases such as AIDS and tuberculosis, and have generally reduced mortality and improved standards of living.[6]

Spending

Relative to the rest of Latin America, Peru does not spend very much on health care for its citizens. 2004 reports showed that spending in Peru was 3.5 percent of its GDP, compared to 7 percent for the rest of Latin America. Additionally, Peru spent $100 USD per capita on health in 2004, compared to an average of $262 USD per capita that was spent by the rest of the countries in Latin America.[23] However, Peru does spend more on healthcare than it does on its military, which differentiates it from many other Latin American countries.[6]

See also

References

- "WHO Global Health Workforce Alliance: Peru". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- (http://www.hydrant.co.uk), Site designed and built by Hydrant (2016-02-14). "Rising coverage improves outlook for Peru health care". Oxford Business Group. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- "WHO | Peru". www.who.int. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- "Mandatory Rural Service: A Primary Care Lesson From Peru - Primary Care Progress". Primary Care Progress. 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- Peru: Improving health care for the poor (1999).

- Borja, A. (2010). Medical pluralism in Peru—Traditional medicine in peruvian society.

- Montenegro, Raul A.; Stephens, Carolyn (2006-06-03). "Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1859–1869. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68808-9. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 16753489.

- Guibovich del Carpio, Lorgio A. (1989). Medicina folklórica en el antiguo Perú y su proyección en el mundo moderno. Enciclopedia boliviana. Lima, Peru: Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales : Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. ISBN 9788483701690.

- "Tourism Opens New Doors, Creates New Challenges, for Traditional Healers in Peru". Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Mathez-Stiefel, Sarah-Lan; Vandebroek, Ina; Rist, Stephan (2012-07-24). "Can Andean medicine coexist with biomedical healthcare? A comparison of two rural communities in Peru and Bolivia". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 8: 26. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-26. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 3485100. PMID 22827917.

- Bussmann, R. W.; Sharon, D.; Lopez, A. (2007-12-31). "Blending Traditional and Western Medicine: Medicinal plant use among patients at Clinica Anticona in El Porvenir, Peru". Ethnobotany Research and Applications. 5: 185–199. doi:10.17348/era.5.0.185-199. ISSN 1547-3465.

- Giovannini, Peter; Heinrich, Michael (2009-01-30). "Xki yoma' (our medicine) and xki tienda (patent medicine)--interface between traditional and modern medicine among the Mazatecs of Oaxaca, Mexico". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 121 (3): 383–399. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.003. ISSN 1872-7573. PMID 19041707.

- Mathez-Stiefel, Sarah-Lan; Vandebroek, Ina (2012). "Distribution and Transmission of Medicinal Plant Knowledge in the Andean Highlands: A Case Study from Peru and Bolivia". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 959285. doi:10.1155/2012/959285. ISSN 1741-427X. PMC 3235884. PMID 22203885.

- McKinley, Michelle (24 September 2010). "Planning Other Families: Negotiating Population and Identity Politics in the Peruvian Amazon". Identities. 10: 31–58. doi:10.1080/10702890304340.

- Bristol, Nellie (July–August 2009). "Dying To Give Birth: Fighting Maternal Mortality In Peru". Health Affairs. 28 (4): 997–1002. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.997. PMID 19597198.

- Brierley, Charlotte (2014). "Healthcare Access and Health Beliefs of the Indigenous Peoples in Remote Amazonian Peru" (PDF). The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 90: 180–103. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0547. PMID 24277789 – via PubMed.

- Bussmann, Rainer (28 December 2013). "The Globalization of Traditional Medicine in Northern Peru: From Shamanism to Molecules". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 291903. doi:10.1155/2013/291903. PMC 3888705. PMID 24454490.

- Brierley, Charlotte (2014). "Healthcare Access and Health Beliefs of the Indigenous Peoples in Remote Amazonian Peru" (PDF). The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 90: 180–103. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0547. PMID 24277789 – via PubMed.

- Oeser, Clarissa (September 2005). "Does traditional medicine use hamper efforts at tuberculosis control in urban Peru?". The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (3): 571–575. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.571. PMID 16172483.

- RENAES: Registro Nacional de Establecimientos de Salud y Servicios Medicos de Apoyo, "RENAES". Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Global Health Intelligence, "Global Health Intelligence" Archived 2017-01-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "Ministerio de Salud del Perú". MINSA. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- Cotlear, D. (Ed.). (2006)

- www.justlanded.com https://www.justlanded.com/english/Peru/Peru-Guide/Health/Public-vs-private-health-care-in-Peru. Retrieved 2018-12-13. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - EsSalud: Seguridad Social para todos. (2012)

- www.justlanded.com https://www.justlanded.com/english/Peru/Peru-Guide/Health/Public-vs-private-health-care-in-Peru. Retrieved 2018-12-13. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Young, F., & Merschrod, K. (2009)

Bibliography

- Borja, A. (2010). Medical pluralism in Peru—Traditional medicine in peruvian society . (Master in Arts in Global Studies, Brandeis University).

- Cotlear, D. (Ed.). (2006). A new social contract for peru: An agenda for improving education, health care, and the social safety net. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- EsSalud: Seguridad Social para todos. (2012). Plan estrategico institucional 2012-2016. Lima, Peru.

- Ministerio de salud del peru. (2012). Retrieved Dec/10, 2012, (Minsa.gob.pe)

- Peru: Improving health care for the poor (1999). . Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Raul A Montenegro, Carolyn Stephens. (2006). Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet, 367, October 28, 2012 – 1859-69.

- Young, F., & Merschrod, K. (2009). Child health and NGOs in peruvian provinces., Dec 12, 2012.