Hawley Harvey Crippen

Hawley Harvey Crippen (September 11, 1862 – November 23, 1910), usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopath, ear and eye specialist and medicine dispenser. He was hanged in Pentonville Prison in London for the murder of his wife Cora Henrietta Crippen, and was the first suspect to be captured with the aid of wireless telegraphy.

Hawley Harvey Crippen | |

|---|---|

Crippen, c. 1910 | |

| Born | September 11, 1862 Coldwater, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | November 23, 1910 (aged 48) Barnsbury, London, England |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | HM Prison Pentonville |

| Occupation | Homeopath |

| Known for | First suspect to be captured with the aid of wireless telegraphy |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse(s) | Corrine Henrietta Turner

( m. 1894; died 1910) |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | Corrine Henrietta Crippen |

| Date | c. January 31, 1910 |

Date apprehended | July 31, 1910 |

Early life and career

Crippen was born in Coldwater, Michigan,[1] to Andresse Skinner[2] (died 1909) and Myron Augustus Crippen[3] (1827–1910), a merchant.[4] Crippen studied first at the University of Michigan Homeopathic Medical School and graduated from the Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College in 1884.[5] Crippen's first wife, Charlotte, died of a stroke in 1892, and Crippen entrusted his parents, living in California, with the care of his two-year-old son, Hawley Otto.[5]

Having qualified as a homeopath, Crippen started to practice in New York, where in 1894 he married his second wife,[4] Corrine "Cora" Turner[6] (stage name: Belle Elmore), born Kunigunde Mackamotski to a German mother and a Polish-Russian father. She was a would-be music hall singer who openly had affairs. In 1894 Crippen started working for Dr Munyon's, a homeopathic pharmaceutical company.

In 1897, Crippen moved to England with his wife,[4] although his US medical qualifications were not sufficient to allow him to practise as a doctor in the UK.[7] As Crippen continued working as a distributor of patent medicines,[8] Cora socialised with a number of variety players of the time, including Lil Hawthorne of The Hawthorne Sisters and Lil's husband/manager John Nash.[9]

Crippen was sacked by Munyon's in 1899 for spending too much time managing his wife's stage career. He became manager of Drouet's Institution for the Deaf, where he hired Ethel Le Neve, a young typist, in 1900. By 1905, the two were having an affair.[4] After living at various addresses in London, the Crippens finally moved in 1905 to 39 Hilldrop Crescent, Camden Road, Holloway, London, where they took in lodgers to augment Crippen's meagre income. Cora cuckolded Crippen with one of these lodgers, and in turn Crippen took Le Neve as his mistress in 1908.[4]

Murder and disappearance

After a party at their home on 31 January 1910, Cora disappeared. Hawley Crippen claimed that she had returned to the United States and later added that she had died and had been cremated in California. Meanwhile, his lover, Ethel "Le Neve" Neave, moved into Hilldrop Crescent and began openly wearing Cora's clothes and jewellery.

Police first heard of Cora's disappearance from her friend, the strongwoman Kate Williams, better known as Vulcana,[10] but began to take the matter more seriously when asked to investigate by a personal friend of Scotland Yard Superintendent Frank Froest, John Nash and his entertainer wife, Lil Hawthorne.[11] The house was searched but nothing was found and Crippen was interviewed by Chief Inspector Walter Dew. Crippen admitted that he had fabricated the story about his wife having died and explained that he had made it up in order to avoid any personal embarrassment because she had in fact left him and fled to America with one of her lovers, a music hall actor named Bruce Miller. After the interview (and a quick search of the house), Dew was satisfied with Crippen's story. However, Crippen and Le Neve did not know this and fled in panic to Brussels, where they spent the night at a hotel. The following day, they went to Antwerp and boarded the Canadian Pacific liner SS Montrose for Canada.

Their disappearance led the police at Scotland Yard to perform another three searches of the house. During the fourth and final search, they found the torso of a human body buried under the brick floor of the basement. William Willcox (later Sir William Willcox, senior scientific analyst to the Home Office) found traces of the calming drug scopolamine in the torso parts.[12] The corpse was identified by a piece of skin from its abdomen; the head, limbs, and skeleton were never recovered. Cora's remains were later interred at the St Pancras and Islington Cemetery, East Finchley.[13]

Transatlantic arrest

Meanwhile, Crippen and Le Neve were crossing the Atlantic on Montrose, with Le Neve disguised as a boy. Captain Henry George Kendall recognised the fugitives and, just before steaming beyond the range of his ship-board transmitter, had telegraphist Lawrence Ernest Hughes send a wireless telegram to the British authorities: "Have strong suspicions that Crippen London cellar murderer and accomplice are among saloon passengers. Mustache taken off growing beard. Accomplice dressed as boy. Manner and build undoubtedly a girl." Had Crippen travelled third class, he probably would have escaped Kendall's notice. Dew boarded a faster White Star liner, SS Laurentic, from Liverpool and arrived in Quebec, Canada, ahead of Crippen, and contacted the Canadian authorities.

As Montrose entered the St. Lawrence River, Dew came aboard disguised as a pilot. Canada was then still a dominion within the British Empire. If Crippen, an American citizen, had sailed to the United States instead, even if he had been recognised, it would have taken extradition proceedings to bring him to trial. Kendall invited Crippen to meet the pilots as they came aboard. Dew removed his pilot's cap and said, "Good morning, Dr. Crippen. Do you know me? I'm Chief Inspector Dew from Scotland Yard." After a pause, Crippen replied, "Thank God it's over. The suspense has been too great. I couldn't stand it any longer." He then held out his wrists for the handcuffs. Crippen and Le Neve were arrested on board the Montrose on 31 July 1910. Crippen was returned to England on board the SS Megantic.[14]

Trial

Crippen was put on trial at the Old Bailey before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Alverstone on 18 October 1910. The proceedings would last four days.

The first prosecution witnesses were pathologists that included Bernard Spilsbury who testified they could not identify the torso remains or even discern whether they were male or female. However, Bernard Spilsbury found a piece of skin with what he claimed to be an abdominal scar consistent with Cora's medical history.[7][15] Large quantities of the toxic compound hyoscine were found in the remains, and Crippen had bought the drug before the murder from a local chemist.

Crippen's defence, led by Alfred Tobin,[16] maintained that Cora had fled to America with another man named Bruce Miller and that Cora and Hawley had been living at the house since only 1905, suggesting a previous owner of the house was responsible for the placement of the remains. The defence asserted that the abdominal scar identified by pathologist Spilsbury was really just folded tissue, for among other things, it had hair follicles growing from it, something scar tissue could not have;[17] Spilsbury noted that the sebaceous glands appeared at the ends but not in the middle of the scar.[7]

Other evidence presented by the prosecution included a piece of a man's pyjama top supposedly from a pair Cora had given Crippen a year earlier. The pyjama bottoms were found in Crippen's bedroom, but not the top. The fragment included the manufacturer's label, Jones Bros. Curlers, and bleached hair consistent with Cora's were found with the remains.[18] Testimony from a Jones Bros. representative, the store that the pyjama top fragment came from, stated that the product was not sold prior to 1908, thus placing the date of manufacture well within the time period of when the Crippens occupied the house and when Cora gave the garment to Hawley the year before in 1909.[17]

Throughout the proceedings and at his sentencing, Crippen showed no remorse for his wife, only concern for his lover's reputation. The jury found Crippen guilty of murder after just 27 minutes of deliberations. Le Neve was charged only with being an accessory after the fact and acquitted.[4]

Although Crippen never gave any reason for killing his wife, several theories have been propounded. One was by notable Late Victorian and Edwardian barrister Edward Marshall Hall who believed that Crippen was using hyoscine on his wife as a depressant or anaphrodisiac but accidentally gave her an overdose and then panicked when she died.[7] It is said that Hall declined to lead Crippen's defence because another theory was to be propounded.[19]

In 1981, several British newspapers reported that Sir Hugh Rhys Rankin claimed to have met Ethel Le Neve in 1930 in Australia where she told him that Crippen murdered his wife because she had syphilis.[20]

Execution

Crippen was hanged by John Ellis at Pentonville Prison, London at 9 am on Wednesday 23 November 1910.[4][21][22]

Le Neve sailed to the United States before settling in Canada finding work as a typist. She returned to England in 1915 and died in 1967. At his request, her photograph was placed in his coffin and buried with him.

Although Crippen's grave in Pentonville's grounds is not marked by a stone, tradition has it that soon after his burial, a rose bush was planted over it. Some of his relatives in Michigan have begun lobbying for his remains to be repatriated to the United States.[17]

Crippen's guilt

Questions have arisen about the investigation, trial and evidence that convicted Crippen in 1910. Dornford Yates, a junior barrister at the original trial, wrote in his memoirs As Berry and I Were Saying, that Lord Alverstone took the very unusual step, at the request of the prosecution, of refusing to give a copy of the sworn affidavit used to issue the arrest warrant to Crippen's defence counsel. The judge without challenge accepted the prosecution's argument that the withholding of the document would not prejudice the accused's case. Yates said he knew why the prosecution did this but - despite the passage of years - refused to disclose why.[23] Yates noted that although Crippen placed the torso in dry quicklime to be destroyed, he did not realise that when it became wet it turned into slaked lime, which is a preservative: a fact that Yates used in the plot of his novel The House That Berry Built.

The American-British crime novelist Raymond Chandler thought it unbelievable that Crippen could be so stupid as to bury his wife's torso under the cellar floor of his home while successfully disposing of her head and limbs.[24]

Another theory is that Crippen was carrying out illegal abortions and the torso was that of one of his patients who died and not his wife.[25]

New scientific evidence

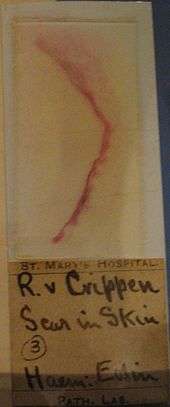

In October 2007, Michigan State University forensic scientist Dr David Foran claimed that mitochondrial DNA evidence showed the remains found beneath Crippen's cellar floor were not those of his wife, Cora Crippen. Researchers used genealogy to identify three living relatives of Cora Crippen (great-nieces). By providing mitochondrial DNA haplotype, researchers were able to compare their DNA with DNA extracted from a microscope slide containing flesh taken from the torso in Crippen's cellar.[26][27] The original remains were also tested using a highly sensitive assay of the Y chromosome that found the flesh sample on the slide was male.[28]

The same research team also argued that a scar found on the torso's abdomen, which the original trial's prosecution argued was the same one Mrs. Crippen was known to have, was incorrectly identified. But the scientists found hair follicles in the tissue which should not be present in scars (a medical fact which Crippen's defence used at his trial).[27] Their research was published in the January 2011 issue of the Journal of Forensic Sciences.

However, the new scientific evidence for Crippen's innocence has been disputed.[29][30] English journalist and author, David Aaronovitch, said "As to the body being male, well the American team was using a 'special technique' that is 'very new' and 'done only by this team' and working on a single, century-old slide, described by the team leader as a 'less than optimal sample'".[30] Dr Foran responded by saying "tests showed unequivocally that the remains were male".[17]

Another researcher says they asked New Scotland Yard to provide samples of the blonde hair found in curlers at the scene (and now preserved in New Scotland Yard's museum) for DNA testing but the request has been denied several times.[17] However, New Scotland Yard was willing to test a hair from the crime scene for a fee, which in turn was rejected by the investigators as "over the top."[17] Researchers have hypothesized that the police planted the body parts and particularly the fragment of the pyjama top at the scene to incriminate Crippen. He suggests that Scotland Yard was under tremendous public pressure to find and bring to trial a suspect for this heinous crime. An independent observer points out that the case did not become public until after the remains were found.[17]

In December 2009, the UK's Criminal Cases Review Commission, having reviewed the case, declared that the Court of Appeal will not hear the case to pardon Crippen posthumously.[31]

Media portrayals

- Kate Bush mentioned Crippen in her 1978 song "Coffee Homeground" about a poisoner - "...pictures of Crippen, lipstick smeared..."

- The murder inspired Arthur Machen's 1927 short story "The Islington Mystery", which in turn was adapted as the 1960 Mexican film El Esqueleto de la señora Morales.

- The gang defeated by Elsa Lanchester in the H.G. Wells-scripted crime comedy Blue Bottles (1928) is revealed to be related to the Crippen case.

- It is thought to have inspired the 1935 novel We, the Accused by Ernest Raymond.

- The German 1942 feature film Doctor Crippen stars Rudolf Fernau in the title role.

- The story of Dr. Crippen is retold in the act 1 finale of the 1943 Broadway musical One Touch of Venus.

- A German sequel of Dr. Crippen an Bord was named Dr. Crippen lebt (1957).

- The 1961 Wolf Mankowitz musical Belle at the Strand Theatre in London was based on the case.

- The British 1962 feature film Dr. Crippen stars Donald Pleasence in the title role and Samantha Eggar as Le Neve.

- In the 20 December 1965 episode of the BBC sitcom Meet the Wife titled "The Merry Widow", Thora Hird says "Look, If I believed you... Crippen would be innocent."

- The British 1968 film Negatives features Peter McEnery and Glenda Jackson as a couple whose erotic fantasies involve dressing up as Crippen and Ethel le Neve.

- The American TV series Ironside presented an episode (season 2, episode 16, January 23, 1969: "Why the Tuesday Afternoon Bridge Club Met on Thursday") in which a neurotic man assumed Dr. Crippen's identity and committed a similar murder.

- In Carry On Loving, which was made and set in 1970, there is a jokily anachronistic reference to the Crippen case: Peter Butterworth appears in Edwardian costume as 'Dr Crippen', visiting a marriage bureau to seek a third wife, having dispatched both his first two.

- The 1981 TV series Lady Killers episode "Miss Elmore" covers the case.

- The Crippen saga is the basis for 1982's The False Inspector Dew, a detective novel by Peter Lovesey.

- The 1989 BBC series Shadow of the Noose, about the life of barrister Edward Marshall Hall, includes an abortive attempt on Hall's part to defend Crippen (played by David Hatton).

- Crippen is mentioned several times in the BBC series Coupling, series 1, episode 1, titled “Flushed”, as a running gag and an ongoing argument between Jane and Steve about continuing their relationship.

- John Boyne wrote the 2004 novel Crippen—A Novel of Murder.

- Erik Larson's 2006 book Thunderstruck interwove the story of the murder with the history of Guglielmo Marconi's invention of radio.

- In the BBC Radio 4 series [32] Old Harry's Game, series 6, episode 3 (2008), Satan mentions Dr Crippen in hell.

- Martin Edwards wrote the 2008 novel Dancing for the Hangman, which re-interprets the case while seeking to adhere to the established evidence.

- The PBS series Secrets of the Dead episode "Executed in Error" (2008) explored new findings in the Crippen case.

- In series 1, episode 5 of the British comedy series Psychoville (2009), Reece Shearsmith plays a waxwork figure that comes to life in a dream. Jack the Ripper mistakes him for Crippen, but he is portraying John Reginald Christie.

- The third installment in the TV series Murder Maps is "Finding Dr. Crippen" (2015).

- Dan Weatherer's stage play Crippen (2016) explores the life and crimes of Dr. Hawley Crippen while taking into account new evidence and presenting an alternative theory as to who lay buried beneath the cellar floor.

- In season 4 episode 1 of Blackadder (which takes place in the Great War), Captain Blackadder sneers that the content of the journal “King and Country” is “about as convincing as Doctor Crippen’s defense lawyer.”

- In season 1, episode 7 ("Crash") of ITV's The Royal, consultant surgeon Mr. Rose uses the name "Dr Crippen" instead of his own on his nametag. When the new administrator asks what he does, Mr. Rose replies "Cut people up!" Later, Dr. Alway makes a reference to Dr. Crippen while they are in theatre.

Curiosities

In the Museum of Automata in the Tibidabo Amusement Park in Barcelona, a machine built in 1921 recreates the execution of Dr. Crippen. A waxwork of Crippen was on display from 1910 until 2016 in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussauds in London. During the Dogger Bank earthquake of 1931, the strongest earthquake recorded in the United Kingdom, the head of his waxwork fell off.[33][34]

See also

- John Reginald Christie

- John George Haigh, the 'Acid Bath Murderer'

- Michael Swango

- John Tawell, the first person to be arrested as the result of telecommunications technology.

- Dorothea Waddingham

References

- "Hawley Harvey Crippen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- US Federal Census: Year: 1880; Census Place: San Jose, Santa Clara, California; Roll T9_81; Family History Film: 1254081; Page: 54.3000; Enumeration District: 243; Image: 0335; and 1870 US Federal Census: 1870; Census Place: Coldwater Ward 2, Branch, Michigan; Roll M593_665; Page: 152A; Image: 310; Family History Library Film: 552164.

- Reitwiesner, William Addams. "Ancestry of Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen". wargs.com.

- "Hawley Harvey Crippen", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Elmsley, John (2008). "Molecules of Murder". Cambridge, UK: The Royal Society of Chemistry: 34. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - 1901 England Census: Source Citation: Class: RG13; Piece: 239; Folio: 41; Page: 19.

- Browne, Douglas G.; Tullett, E.V. (1955). Bernard Spilsbury: his life and cases. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 31–54.

- Larson 2006, p. 105

- Larson 2006, p. 159

- Hunt, Jane; Peel, John (August 30, 2004). "Vulcana and Atlas". Home Truths. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- Larson 2006, p. 347-348

- "Old Bailey Proceedings (11th October 1910)".

- "St Pancras Cemetery".

- "Megantic – 1908". Shawsvillships.

- "Will the Devil's advocate get a pardon for Crippen?". Camden New Journal. December 27, 2007. p. 14. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- Preston Herald - Saturday 15 May 1915

- Executed in Error:Secrets of the Dead; broadcaster: PBS, Original US broadcast date: October 2008 at the Wayback Machine (archived November 14, 2012)

- Elmsley, p.42

- Young, Filson (1954). Harry Hodge (ed.). Famous Trials. I. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 124.

- Gaute, J. H. H.; Odell, Robin (1991). The new murderers' who's who. Dorset Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-88029-582-6.

- Fields, Kenneth (1998). Lancashire magic & mystery: secrets of the Red Rose County. Sigma. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-85058-606-7.

- Smith, David James (2010). Supper with the Crippens. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-4091-3413-8.

- As Berry And I Were Saying ISBN 0-755-10036-0 p. 253

- Chandler, Raymond (1997). Raymond Chandler Speaking. University of California Press. pp. 197. ISBN 978-0-520-20835-3. (Letter to James Sandoe 15 December 1948)

- Cockcroft, Lucy (October 17, 2007). "US scientists: Dr Crippen was innocent". Telegraph. London. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Hodgson, Martin (October 16, 2007). "100 years on, DNA casts doubt on Crippen case". The Guardian. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- Foster, Patrick (October 17, 2007). "Doctor Crippen may have been innocent". The Times. London. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- "Was Dr Crippen innocent of his wife's murder?". BBC NEWS. July 29, 2010.

- Menges, Jonathan (2008). "'Another World and Another Judge': Do New Scientific Tests Clear Crippen?". Ripper Notes #28: The Legend Continues. Inkling Press. ISBN 978-0-9789112-2-5.

- Aaronovitch, David (July 1, 2008). "I'll eat my hat if Dr Crippen was innocent – OK?". The Times. London.

- "lawmentor.co.uk". Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Old Harry's Game

- Hough, Andrew (September 10, 2010). "Police given earthquake training for 'extremely unlikely crisis'". The Telegraph.

- Davies, Carey (November 29, 2012). "Earthquake hits the Lake District". TGO Magazine. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

Further reading

- Connell, Nicholas (2005). Walter Dew; The Man Who Caught Crippen. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3803-7.

- Cullen, Tom (1977). The Mild Murderer: The True Story of the Dr. Crippen Case. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-395-25776-0.

- Dalrymple, Roger (2020). Crippen: A Crime Sensation in Memory and Modernity. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-7874-4677-9.

- Goodman, Jonathan, ed. (1985). The Crippen File. London, New York: Allison & Busby, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85031-636-0.

- Gaute, J.H.H.; Odell, Robin (1996). The New Murderer's Who's Who. London: Harrap Books. ISBN 978-0-245-54639-6.

- Smith, David James (2005). Supper with the Crippens. Orion Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7528-7772-3.

- Larson, Erik (2006). Thunderstruck. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4000-8067-0.

- Saward, Joe (2010). The Man who Caught Crippen. Paris: Morienval Press. ISBN 978-0-9554868-1-4.

- The World's Most Infamous Crimes and Criminals. New York: Gallery Books. 1987. ISBN 978-0-8317-9677-8. OCLC 17304744.

- "Crippen, Hawley Harvey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39420. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Finn, Pat (2016) Unsolved 1910. ISBN 978-1535461856

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hawley Harvey Crippen. |

- Geringer, Joseph (2014). "Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen: Of Passion and Poison". truTV Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 11, 2003. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "Dr. Crippen: One Night In Camden". marconicalling.com. 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "Crippen mystery remains despite DNA claim". BBC News. London: BBC. October 18, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "Hawley Harvey Crippen: Witness statements and edited proceeding from records held at The Old Bailey". Old Bailey Online. 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- Le Queux, William (May 1930). "The Girl, the Doctor—and the Missing Wife". True Detective Mysteries. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- Hilton, Chris (July 31, 2010). "Murder, he telegraphed". Wellcome Library. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "Hawley Harvey Crippen was convicted of the murder of his wife Cora Crippen and sentenced to death". Black Kalendar. October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.