Hashish

Hashish, or hash, is a drug made from the resin of the cannabis plant.[2] It is consumed by inhaling from a small piece, typically in a pipe, bong, vaporizer or joint, or via oral ingestion (after decarboxylation). As pure hashish will not burn if rolled alone in a joint, it is typically mixed with herbal cannabis, tobacco or another type of herb for this method of consumption. Depending on region or country, multiple synonyms and alternative names exist.[3]

| Hashish | |

|---|---|

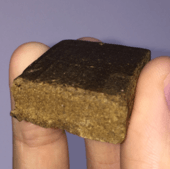

Hashish (shown next to a U.S. penny for scale) | |

| Product name | Hashish |

| Source plant(s) | Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, Cannabis ruderalis |

| Part(s) of plant | Trichome |

| Geographic origin | Central and South Asia[1] |

| Active ingredients | Tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, cannabinol, tetrahydrocannabivarin |

| Legal status |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Regional

|

|

Variants |

|

.jpg)

Hash is a cannabis concentrate product composed of compressed or purified preparations of stalked resin glands, called trichomes, from the plant. It is defined by the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Schedule I and IV) as "the separated resin, whether crude or purified, obtained from the cannabis plant". The resin contains ingredients such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other cannabinoids—but often in higher concentrations than the unsifted or unprocessed cannabis flower.[4] Purities of confiscated hashish in Europe (2011) range between 4% and 15%. Between 2000 and 2005 the percentage of hashish in cannabis end product seizures was at 18%.[2]

Hashish may be solid or resinous depending on both preparation and room temperature; pressed hashish is usually solid, whereas water-purified hashish—often called "bubble melt hash", or simply "bubble hash"—is often a paste-like substance with varying hardness and pliability; its color, most commonly light to dark brown, can vary from transparent to yellow, tan, black, or red. This all depends on the process and amount of leftover plant material (e.g. chlorophyll). [5]

Hashish was the primary form of cannabis used in Europe in 2008. Herbal cannabis is more widely used in Northern America.[2]

History

Hashish has been consumed for many centuries, though there is no clear evidence as to its first appearance.[6] North India and Nepal have a long social tradition in the production of hashish, known locally as charas.[7]

The first attestation of the term "hashish" is in a pamphlet published in Cairo in 1123 CE, accusing Nizari Muslims of being "hashish-eaters".[8] The 13th-century Ibn Taymiyyah prohibited the use of hashish; he mentioned that it was introduced to Levant with the Mongol invasion (throughout the 13th century).[9] Smoking did not become common in the Old World until after the introduction of tobacco: until the 1500s hashish in the Muslim world was consumed as an edible.[10]

In 1596, Dutchman Jan Huyghen van Linschoten spent three pages on "Bangue" (bhang) in his historic work documenting his journeys in the East. He particularly mentioned the Egyptian hashish.[11] He said, "Bangue is likewise much used in Turkie and Egypt, and is made in three sorts, having also three names. The first by the Egyptians is called Assis (Hashish (Arab.)), which is the poulder of Hemp, or of Hemp leaves, which is water made in paste or dough, they would eat five pieces, (each) as big as a Chestnut (or larger); This is used by the common people, because it is of a small price, and it is no wonder, that such vertue proceedeth from the Hempe, for that according to Galens opinion, Hempe excessively filleth the head."[12]

Western world

Hashish arrived in Europe from the East during the 18th century,[2] and is first mentioned scientifically by Gmelin in 1777.[2] The Napoleonic campaigns introduced French troops to hashish in Egypt and the first description of usefulness stems from 1830 by pharmacist and botanist Theodor Friedrich Ludwig Nees von Esenbeck.[2] In 1811, the founder of homoeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, published a "proving" of the effects of Cannabis Sativa in his work Reine Arzneimittellehre (Materia Medica Pura).

In 1839, O’Shaughnessy wrote a comprehensive study of Himalayan hemp, which was recognised by the European school of medicine and describes hashish as relief for cramps and causing the disappearance of certain symptoms from afflictions such as rabies, cholera, and tetanus.[2] This led to high hopes in the medical community. In 1840 Louis Aubert-Roche reported his successful use of hashish against pestilence.[2] Also psychiatric experiments with hashish were done at the same time with Jacques-Joseph Moreau being convinced that it is the supreme medicament for use in psychiatry.[2]

In the 19th century, hashish was embraced in some European literary circles. Most famously, the Club des Hashischins was a Parisian club dedicated to the consumption of hashish and other drugs; its members included literary luminaries such as Théophile Gautier, Dr. Moreau de Tours, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Charles Baudelaire and Honoré de Balzac.[13] Baudelaire later wrote the 1860 book Les paradis artificiels, about the state of being under the influence of opium and hashish. At around the same time, American author Fitz Hugh Ludlow wrote the 1857 book The Hasheesh Eater about his youthful experiences, both positive and negative, with the drug.

Hashish was also mentioned and used as an anaesthetic in Germany in 1869. It was imported in great quantities especially from India and called charas. However, there were also people who did not deem cannabis as harmless.[2] Between 1880 and 1900 was the peak of the medicinal use, where hashish compounds were most commonplace in almost all European countries and the USA. Evidence of misuse at that time was practically non-existent (as opposed to widespread reports in Asia and Africa).[2] Hashish played a significant role in the treatment of pain, migraine, dysmenorrhea, pertussis, asthma and insomnia in Europe and USA towards the end of the 19th century. Rare applications included stomach ache, depression, diarrhea, diminished appetite, pruritus, hemorrhage, Basedow syndrome and malaria.[2] The use was later prohibited worldwide as the use as a medicine was made impossible by the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

International trade

At the beginning of the 20th century, the majority of hashish in Europe came from Kashmir and other parts of India, Afghanistan, as well as Greece, Syria, Nepal, Lebanon, and Turkey. Larger markets developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s when most of the hashish was imported from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Due to disruptive conflicts in the regions, Morocco took over and was the sufficient exporter until lately.[14] It is believed that massive hashish production for international trade originated in Morocco during the 1960s, where the cannabis plant was widely available. Before the coming of the first hippies from the Hippie Hashish Trail, only small pieces of Lebanese hashish were found in Morocco.[6]

However, since the 2000s there has been a dramatic shift in the market due to an increase of homegrown cannabis production. While Morocco held a quasi-monopoly on hashish in the 1990s with the 250g so-called "soap bar" blocks, which were of low quality, Afghanistan is now regarded as the biggest producer of higher quality hashish. Since then, hashish quality in Europe has increased while its prices have remained stable.[2]

Hashish remains in high demand in most of the world while quality continues to increase, due to many Moroccan and western farmers in Morocco and other hash producing countries using more advanced cultivation methods as well as cultivating further developed cannabis strains which increases yields greatly, as well as improving resin quality with higher ratios of psychoactive ingredients (THC). A tastier, smoother and more aromatic terpenes and flavanoids profile is seen as an indicator of a significant rise in hashish quality in more recent years. Hashish production in Spain has also become more popular and is on the rise, however the demand for relatively cheap and high quality Moroccan hash is still extremely high.

Changes to regulations around the world have contributed greatly to more and more countries becoming legitimate hashish producing regions, with countries like Spain effecting more lenient laws on cannabis products such as hashish, California regulating cultivation, manufacturing and distribution of cannabis and cannabis derived products such as hashish,

European market

According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Western Europe is the biggest market for cannabis resin with 70% of global seizures. The European hashish market is changing though: Cannabis cultivation increased throughout the 1990s until 2004, with a noticeable decrease reported in 2005 according to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.[2] Morocco has been the major source, however lately there has been a shift in the market and Afghanistan has been named the major producer of Hashish. Even though a drop in usage and production has been reported, Morocco produced around 6600 tonnes of resin in 2005.[2]

As 641 tonnes of hashish were consumed in the EU in 2013, the European market is currently the world’s largest and most profitable. Therefore, many players are involved in the business, including organised crime groups. The largest cannabis resin seizures in Europe happen in Spain, due to its proximity to Northern Africa.[2]

The 1990s "soap bars" disappeared and the physical shapes of hashish changed to melon shaped, tablets or olive shaped pellets. Overall the general trend of domestically grown cannabis displacing the imported resin leads to a market reaction of potency changes while the prices remain stable while soap-bar potency increased from 8% to up to 20.7% in 2014.[2]

Generally, more resin than herb is consumed in Europe.[2]

Substance properties

As hashish is a derivative of cannabis, it possesses identical psychoactive and biological effects. When smoked, THC can be detected in plasma within seconds, with a half-life of two hours. Due to its lipophilic nature, it is widely distributed through the body, and some metabolites can be detected in urine for up to two weeks following consumption.[15]

Hashish is made from cannabinoid-rich glandular hairs known as trichomes, as well as varying amounts of cannabis flower and leaf fragments.[16] The flowers of a mature female plant contain the most trichomes, though trichomes are also found on other parts of the plant. Certain strains of cannabis are cultivated specifically for their ability to produce large amounts of trichomes. The resin reservoirs of the trichomes, sometimes erroneously called pollen (vendors often use the euphemism "pollen catchers" to describe screened kief-grinders in order to skirt paraphernalia-selling laws), are separated from the plant through various methods.

Application

Set and setting

Hashish is often consumed in a social setting, being smoked by multiple people who share a pipe, bong, joint or vaporizer.

After effects

The pharmacology of hashish is complicated because of the wide range of cannabinoids. There is little evidence for damage to the organ system, only due to the consumption in combination with tobacco.[17] There has also been an association with schizophrenia, however it is unclear if there is a causative relationship.[15]

Generally the after effects are the same as for cannabis use in general, including its long term effects.[18]

Use

Hashish can be consumed by oral ingestion or smoking; typically in a pipe, bong, vaporizer or joints, where it is normally mixed with cannabis or tobacco, as pure hashish will burn poorly if burned alone. In many parts of the world, individuals do what are known as "buckets", in which they take a bottle with the bottom cut off and put it in a bucket of water, they then take a pipe bowl and put it in the top of the bottle, stick a "slab" (large hashish ball) in then let the smoke fill the bottle before inhalation. THC has a low water solubility therefore ingestion should be done alongside a fatty meal or snack.[15] It is important to note that not all hashish can be consumed orally as some are not decarboxylated during manufacture. Generally the methods are similar to overall cannabis consumption.

While hashish is a type of concentrate, it is often made into rosin, a solventless extract made by applying pressure and heat to cannabis derivatives. Bubble hash is one such hashish commonly made into rosin. When fresh or fresh-frozen plant material is used as the starting material the resulting product is called "live hash rosin"

Altered state

As the active ingredient of hashish is THC, it has the same effects as cannabis. The most well known effect of hashish is a euphoric, drowsy, sedated effect. A certain relief of anxiety is often reported.[19] During a high, the user experiences a distortion of time and space perception.[20]

It has been claimed that the user’s psychological and physiological needs will influence the response and that the user must cooperate with and facilitate the effects. Therefore, the effect of the physical and interpersonal setting is strong and usually controls the underlying tone of the experience.[20] Generally the intensification of sensation and increased clarity of perception have been reported.[20] Adverse effects have been reported, including psychotic states following heavy consumption.[21] People with major mental illnesses (e.g. schizophrenia) are especially vulnerable, as hashish provokes relapse and aggravates existing symptoms.[19]

Perceptual changes

As perceptual changes are very hard to measure, most studies on the altered state of consciousness concentrate on subjective descriptions only. The general awareness of proprioceptive responses seem to enhance, as emotional involvement is reported to enhance perception in general. Taste and smell seem intensified and visual scenes seem to have more depth while sounds are heard with more dimension.[20] Perception of time is also reported to change: there is a general experience of time distortion where events take longer to occur and the subject is involved in internal fantasies with the impression that external time has slowed down.[20] However, there seems to be no impression of speed or rapidity for internal processes. Similar effects are common in normal experience, for example when time slows down in boredom. It is proposed that this distortion is caused as the experience itself is the focus of attention rather than what is happening around the individual.[20]

Functional associations seem to decrease in strength and there are fewer mental impositions on the sensory perception of the object. Aspects which are normally filtered out are given equal attention. Therefore, objects are not necessarily conceptualized via their use but rather experienced as a whole.[20] Detailed attention is paid, focussing on certain aspects of an object, a sentence or any other perceptual input in a magnifying way. Clearly the attention process is affected. Only a narrow amount of diverse content is the focus of attention and fewer objects are perceived.[20] A person may become absorbed by one object, event or process up to the exclusion of everything else, which has been called a train of fantasy and has been described as a form of tunnel vision where the individual is more aware of an individual element of meaning, emotion etc. There seems to be a certain unity of attention while normally attention relies on multiple channels.[20] Flights of fantasy and dreaming, including perceiving connections and associations of ideas that do not seem accessible in a normal state are often reported.[20]

There seems to be a reduction of the automatic availability of memory images, however an increased strength of memories when relevant to central needs.[20] Experiences seem new and are experienced without a feeling of familiarity and is more intense if emotionally salient. This emotional force may activate internal imagery, which is used to search for identity or to interpret incoming stimuli.[20] Short term memory becomes shorter and in a very high state the sequence of thoughts is not remembered past one or two transitions.[20]

Expectancies and anticipation which are important to keep behaviour consistent in normal states seem to be decreased in strength which might lead to surprising or out-of-character behaviour.[20] Normally these expectancies let the person behave in a goal directed and reasonable manner, with the decrease the person might act out in illogical and unforeseeable ways. Similarly inhibitions, especially social inhibition seems to be reduced, resulting in playful behaviour and acting on impulses.[20]

Manufacturing processes

The sticky resins of the fresh flowering female cannabis plant are collected. Traditionally this was done, and still is in remote locations, by pressing or rubbing the flowering plant between two hands and then forming the sticky resins into a small ball of hashish called charas.

Mechanical separation methods use physical action to remove the trichomes from the dried plant material, such as sieving through a screen by hand or in motorized tumblers. This technique is known as "drysifting". The resulting powder, referred to as "kief" or "drysift", is compressed with the aid of heat into blocks of hashish; if pure, the kief will become gooey and pliable. When a high level of pure THC is present, the end product will be almost transparent and will start to melt at the point of human contact.

Ice-water separation is another mechanical method of isolating trichomes. Newer techniques have been developed such as heat and pressure separations, static-electricity sieving or acoustical dry sieving.

.jpg)

Trichomes may break away from supporting stalks and leaves when plant material becomes brittle at low temperatures. After plant material has been agitated in an icy slush, separated trichomes are often dense enough to sink to the bottom of the ice-water mixture following agitation, while lighter pieces of leaves and stems tend to float.[22]

The ice-water method requires ice, water, agitation, filtration bags with various-sized screens and plant material. With the ice-water extraction method the resin becomes hard and brittle and can easily be separated. This allows large quantities of pure resins to be extracted in a very clean process without the use of solvents, making for a more purified hashish.[22][23]

Chemical separation methods generally use a solvent such as ethanol, butane or hexane to dissolve the lipophilic desirable resin. Remaining plant materials are filtered out of the solution and sent to the compost. The solvent is then evaporated, or boiled off (purged) leaving behind the desirable resins, called honey oil, "hash oil", or just "oil". Honey oil still contains waxes and essential oils and can be further purified by vacuum distillation to yield "red oil". The product of chemical separations is more commonly referred to as "honey oil." This oil is not really hashish, as the latter name covers trichomes that are extracted by sieving. This leaves most of the glands intact.

In a study conducted in 2014 by Jean-Jaques Filippi, Marie Marchini, Céline Charvoz, Laurence Dujourdy and Nicolas Baldovini (Multidimensional analysis of cannabis volatile constituents: Identification of 5,5-dimethyl-1-vinylbicyclo[2.1.1]hexane as a volatile marker of hashish, the resin of Cannabis sativa L.) the researchers linked the characteristic flavour of hashish with a rearrangement of myrcene caused during the process of manufacture.[24]

Depending on the production process, the product can be contaminated with different amounts of dirt and plant fragments, varying greatly in terms of appearance, texture, odour and potency. Also, adulterants may be added in order to increase weight or modify appearance.[14]

Morocco has been the major hashish producer globally with €10.8 billion earned from Moroccan resin in 2004, but some so-called "Moroccan" may actually be European-made.[2][14] The income for the farmers was around €325 million in 2005. While the overall number of plants and areas shrank in size, the introduction of more potent hybrid plants produced a high resin rate. The range of resin produced is estimated between 3800 and 9500 tonnes in 2005.[2]

The largest producer today is Afghanistan,[25][26] however studies suggest there is a "hashish revival" in Morocco.[27]

Quality

Tiny pieces of leaf matter may be accidentally or even purposely added; adulterants introduced when the hashish is being produced will reduce the purity of the material and often resulting in green finished product. The tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of hashish comes in wide ranges from almost none to 65% and that of hash oil from 30% to 90%.[28] Hashish can also contain appreciable amounts of CBD, CBN and also contain trace amounts of other cannabinoids[29]

As mentioned above, there has been a general increase in potency as the competition has grown bigger and new hybrid plants have been developed.[14]

Synonyms

Hashish goes by many other names.[30]

See also

References

- Mahmoud A. ElSohly (2007). Marijuana and the Cannabinoids. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-59259-947-9.

- EMCDDA (2008). "A cannabis reader: global issues and local experiences". Monograph Series. 8 (1). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Lisbon, doi:10.2810/13807

- "Hashish". drugs.com. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Russo, Ethan. Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential, p. 34 (Routledge 2013).

- "Guide To The Different Types Of Hashish". www.druglibrary.org.

- Hashish! by Robert Connell Clarke, ISBN 0-929349-05-9

- Usaybia, Abu; Notes on Uyunu al-Anba fi Tabaquat al-Atibba, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965.

- Martin Booth (30 September 2011). Cannabis: A History. Transworld. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-4090-8489-1.

- Ibn Taymiyyah, Majmu al-Fatwa al-Kubra(Arabic), Vol. 3, p 425. http://shamela.ws/browse.php/book-9690#page-1323 Archived 2018-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- John Charles Chasteen (9 February 2016). Getting High: Marijuana through the Ages. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-4422-5470-1.

- Burnell, Arthur Coke; Tiele, P.A (1885). The voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies. from the old English translation of 1598: the first book, containing his description of the East. London: The Hakluyt Society. pp. 115–117. Full text at Internet Archive. Chapter on Bangue.

- Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1885). The Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten to the East Indies: From the Old English Translation of 1598. The First Book, Containing His Description of the East... Hakluyt society. pp. 116–.

- Levinthal, C. F. (2012). Drugs, behavior, and modern society. (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson College Div.

- Chouvy, Pierre-Arnaud. "The supply of hashish to Europe" (PDF). Background Paper Commissioned by the EMCDDA for the 2016 EU Drug Markets Report.

- "Cannabis drug profile". emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Gloss, D (October 2015). "An Overview of Products and Bias in Research". Neurotherapeutics (Review). 12 (4): 731–4. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0370-x. PMC 4604179. PMID 26202343.

- Tashkin, DP (2013). "Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 10 (3): 239–247. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR. PMID 23802821.

- Crean, R.D.; Crane, N.A. (2011). "An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 5 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa. PMC 3037578. PMID 21321675.

- Johns, Andrew (2001). "Psychiatric effects of cannabis" (PDF). British Journal of Psychiatry. 178 (2): 116–122. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.2.116. PMID 11157424.

- Tart, Charles T. (1972). Altered States of Consciousness. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385067287.

- Khan, Masood A; Akella, Sailaja (2009). "Cannabis-Induced Bipolar Disorder with Psychotic Features". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 6 (12): 44–48. PMC 2811144. PMID 20104292.

- Scammel and, Liza; Bianca Sind. "How to Make Wicked hash/Bubble hash". Cannabis Culture Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- Brady, P. (February 4, 2003). "Bubble Hash". Cannabis Culture Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- Alchimia Blog, Hashishene, the new terpene of cannabis

- "UN: Afghanistan world leading hashish producer". PressTV. March 31, 2010. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "UN: Afghanistan is leading hashish producer". Fox News. 2010-03-31.

- Chouvy, Pierre Arnaud; Afsahi, Kenza (2014). "Hashish Revival in Morocco". International Journal of Drug Policy. 25 (3): 416–423. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.001. ISSN 0955-3959. PMID 24507440.

- Inciardi, James A. (1992). The War on Drugs II. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company. p. 19. ISBN 1-55934-016-9.

- "The main cannabinoids content in hashish samples seized in Israel and Czech Republic". Lumir Lab. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- "Hash / Hashish Information". narconon.org. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

Further reading

- Hashish! by Robert Connell Clarke, ISBN 0-929349-05-9

- The Hasheesh Eater by Fitz Hugh Ludlow; first edition 1857

- Marihuana The first twelve thousand years by Ernest L. Abel, 1980, ISBN 0-306-40496-6

- Starks, Michael. Marijuana Potency. Berkeley, California: And/Or Press, 1977. Chapter 6 "Extraction of THC and Preparation of Hash Oil" pp. 111–122. ISBN 0-915904-27-6.

External links

| Look up hashish in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Hashish. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hashish. |