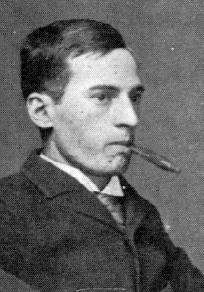

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (December 5, 1872 – June 17, 1906) was a leading American chess player. At the age of 22, he won one of the strongest tournaments of the time (the Hastings 1895 chess tournament) but his illness and early death prevented him from challenging for the World Chess Championship.

| Harry Pillsbury | |

|---|---|

Harry Nelson Pillsbury | |

| Full name | Harry Nelson Pillsbury |

| Country | United States |

| Born | December 5, 1872 Somerville, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | June 17, 1906 (aged 33) |

Biography

Early life

Pillsbury was born in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1872 and moved to New York City in 1894, then to Philadelphia in 1898.

By 1890, having only played chess for two years, he beat noted expert H. N. Stone. In April 1892, Pillsbury won a match two games to one against World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz, who gave him odds of a pawn. Pillsbury's rise was meteoric, and there was soon no one to challenge him in the New York chess scene.

Hastings 1895

The Brooklyn chess club sponsored his journey to Europe to play in the Hastings 1895 chess tournament, in which all the greatest players of the time participated. The 22-year-old Pillsbury became a celebrity in the United States and abroad by winning the tournament, finishing ahead of reigning world champion Emanuel Lasker, former world champion Wilhelm Steinitz, recent challengers Mikhail Chigorin and Isidor Gunsberg, and future challengers Siegbert Tarrasch, Carl Schlechter and Dawid Janowski.

The dynamic style that Pillsbury exhibited during the tournament also helped to popularize the Queen's Gambit during the 1890s, including his famous win over Siegbert Tarrasch.[1]

St. Petersburg 1895

His next major tournament was the Saint Petersburg 1895-96 chess tournament, a six-round round-robin tournament between four of the top five finishers at Hastings (Pillsbury, Chigorin, Lasker and Steinitz; Tarrasch did not play). Pillsbury appears to have contracted syphilis prior to the start of the event. Although he was in the lead after the first half of the tournament (Pillsbury 6½ points out of 9, Lasker 5½, Steinitz 4½, Chigorin 1½), he was affected by severe headaches and scored only 1½/9 in the second half, ultimately finishing third (Lasker 11½/18, Steinitz 9½, Pillsbury 8, Chigorin 7). He lost a critical fourth cycle encounter to Lasker, and Garry Kasparov has suggested that had he won, he could well have won the tournament and forced a world championship match against Lasker.[2]

U.S. Champion 1897

In spite of his ill health, Pillsbury beat American champion Jackson Showalter in 1897 to win the U.S. Chess Championship, a title he held until his death in 1906.

Decline and death

Poor mental and physical health, the result of a syphilis infection, prevented him from realizing his full potential throughout the rest of his life. He succumbed to the illness in a Philadelphia hospital in 1906.

Pillsbury is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Reading, Massachusetts.

Lifetime records

Pillsbury had an even record against Lasker (+5−5=4), a feat matched or surpassed by few. He even beat Lasker with the black pieces at Saint Petersburg in 1895 and at Augsburg in 1900 (this was an offhand game, however, not a tournament game):

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

- Emanuel Lasker vs. Pillsbury, Augsburg 1900

1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 3.exd5 e4 4.Nc3 Nf6 5.Qe2 Bd6 6.d3 0-0 7.dxe4 Nxe4 8.Nxe4 Re8 9.Bd2 Bf5 10.0-0-0 Bxe4 11.Qg4 f5 12.Qg3 Nd7 13.Bc3 Nf6 14.Nh3 Ng4 15.Be2 Be7 16.Bxg4 (diagram) Bh4 17.Bxf5 Bxg3 18.Be6+ Rxe6 19.dxe6 Qe8 20.hxg3 Bxg2 21.Rhe1 Bxh3 22.Rd7 Qg6 23.b3 Re8 24.Re5 Bxe6 25.Rxc7 Qxg3 26.Kb2 h6 27.Rxb7 Rc8 28.Bd4 Qg2 29.Rxa7 Rxc2+ 30.Kb1 Qd2 0–1

Pillsbury also had an even score against Steinitz (+5−5=3), but a slight minus against Chigorin (+7−8=6), Tarrasch (+5−6=2)[3] and against Joseph Henry Blackburne (+3−5=4), while he beat David Janowski (+6−4=2) and Géza Maróczy (+4−3=7) and had a significant edge over Carl Schlechter (+8−2=9).

Blindfold skill

Pillsbury was a very strong blindfold chess player, and could play checkers and chess simultaneously while playing a hand of whist, and reciting a list of long words. His maximum was 22 simultaneous blindfold games at Moscow 1902. However, his greatest feat was 21 simultaneous games against the players in the Hannover Hauptturnier of 1902—the winner of the Hauptturnier would be recognized as a master, yet Pillsbury scored +3−7=11. As a teenager, Edward Lasker played Pillsbury in a blindfold exhibition in Breslau, against the wishes of his mother, and recalled in Chess Secrets I learned from the Masters :

But it soon became evident that I would have lost my game even if I had been in the calmest of moods. Pillsbury gave a marvellous performance, winning 13 of the 16 blindfold games, drawing two, and losing only one. He played strong chess and made no mistakes [presumably in recalling the positions]. The picture of Pillsbury sitting calmly in an armchair, with his back to the players, smoking one cigar after another, and replying to his opponents' moves after brief consideration in a clear, unhesitating manner, came back to my mind 30 years later, when I refereed Alekhine's world record performance at the Chicago World's Fair, where he played 32 blindfold games simultaneously. It was quite an astounding demonstration, but Alekhine made quite a number of mistakes, and his performance did not impress me half as much as Pillsbury's in Breslau.

Memorization skills

Before his simultaneous chess exhibitions, Pillsbury would entertain his audience with feats of memory that involved accurately recalling long lists of words after hearing or looking at them just once. One such list, which Pillsbury repeated forward and backward, performing the same feat the next day, was:

Antiphlogistine, periosteum, takadiastase, plasmon, ambrosia, Threlkeld, streptococcus, staphylococcus, micrococcus, plasmodium, Mississippi, Freiheit, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, athletics, no war, Etchenberg, American, Russian, philosophy, Piet Potgelter's Rost, Salamagundi, Oomisillecootsi, Bangmamvate, Schlechter's Nek, Manzinyama, theosophy, catechism, Madjesoomalops[4]

Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld, in the Fireside Book of Chess, state that this list was devised by H. Threkeld-Edwards, a surgeon, and Prof. Mansfield Merriman, teacher of civil engineering at Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, who challenged Pillsbury in Philadelphia, PA, before an exhibition in 1896. (Other sources cite the location of the challenge as London, UK.)

References

- Pillsbury vs. Tarrasch Chessgames.com

- Kasparov on Pillsbury, Chessbase, 17-Jun-2006

- Chessgames.com database

- Berry, Joseph F., ed. (June 28, 1902). "Thirty Words You Probably Cannot Remember". Epworth Herald. Vol. 13 no. 5. Chicago: Jennings & Pye. p. 120. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

Further reading

- Cherniaev, Alexander (2006). Harry Nelson Pillsbury: A Genius Ahead of His Time. Books from Europe. ISBN 5903229034.

- Pope, Jacques N. (1996). Harry Nelson Pillsbury: American Chess Champion. Pawn Island Press.

External links

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Edward Winter, Pillsbury's Torment (2002, updated 2005)

- The Boston Globe article

- A New Grave Marker with Reunited Family

| Preceded by Jackson Showalter |

United States Chess Champion 1897–1906 |

Succeeded by Jackson Showalter |