Harriett Ellen Grannis Arey

Harriett Ellen Grannis Arey (sometimes "Harriet" or "Hannah"; pen name, Mrs. H. E. G. Arey; April 14, 1819 – April 26, 1901) was a 19th-century American educator, author, editor, and publisher. Hailing from Vermont, she was one of the earliest young women who studied in a co-educational environment. In Cleveland, Ohio, she became a contributor to the Daily Herald and taught at a girls' school. After marriage, she moved to Wisconsin, and served as "Preceptress and Teacher of English Literature, French, and Drawing" at State Normal School in Whitewater, Wisconsin. After returning to Cleveland, she edited a monthly publication devoted to charitable work, and served on the board of the Woman's Christian Association. Arey was a cofounder and first president of the Ohio Woman's State Press Association. Her principal writings were Household Songs and Other Poems and Home and School Training. Arey died in 1901.

Harriett Ellen Grannis Arey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Harriett Ellen Grannis April 14, 1819 Cavendish, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | April 26, 1901 (aged 82) |

| Resting place | Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Pen name | Mrs. H. E. G. Arey |

| Occupation | educator, author, editor, publisher |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | U.S. |

| Alma mater | Oberlin College |

| Notable works | Household Songs and Other Poems; Home and School Training |

| Spouse | Oliver Arey ( m. 1848) |

Early years and education

Harriett Ellen Grannis was born in Cavendish, Vermont, April 14, 1819.[1] Her parents were John Grannis and Roxana Chandler Grannis. Her father was at that time a merchant and the Grannis family home was across the river in Claremont, New Hampshire. To this place, her grandfather, Timothy Grannis, had moved from New Haven, Conn., the original home of the family in America, had purchased an estate along the bank of the Connecticut and Sugar Rivers, and had married Sarah, daughter of Dr. William Sumner of Boston, Massachusetts. Her mother, Roxana Chandler, was daughter of David Chandler and Hannah Peabody, his wife. These families had settled in the earliest colonial times in Duxbury, Salem, and Boston, a branch of each being found very early in Andover, Massachusetts, from where another branch went, in the middle of the 18th century, to Amherst, New Hampshire. These ancestors were of old colonial and mainly of Puritan background—one of the early comers having married a daughter of Miles Standish,—-and another belonging to a family, one of whose members, while a student at Oxford University, was hunted down for reading Tyndale Bible and other so-called heretical works, at a time when the only purification for such heresies was by burning at the stake.[2]

Her father's family had settled in New Haven, Connecticut, previous to 1655, among the earlier immigrants to New England. A hundred years later, her grandfather moved from New Haven to Claremont, New Hampshire, taking up a section of land included between the Connecticut River and Sugar River and the township boundary on the north. Her father was the seventh child of this family. While he was studying for the ministry, the older brothers engaged in extensive business enterprises. The War of 1812 came with its ruinous effects upon the country, followed from 1815 by two or three cold seasons in New England, in which crops were cut off. The business of the country had been unsettled since the first demonstrations of war, and her father was called from his studies to assist in saving the crippled business in which his brothers were engaged. The last blow of ruined crops brought about a disastrous failure, so that Harriett was born in the midst of a depression. When she was three years of age, her father moved to Woodstock, Vermont.[3] When she was five years of age, the family moved to Stanstead, Lower Canada, and located at Hatley, a small town on Lake Magog. The schools were unusually good, and she received some of her education here.[2]

Her father, as well as his elder brother Timothy, and, still more, a son of the latter, had been accustomed to write in measured rhyme, their poems sometimes appearing in the local papers; and perhaps it was not strange that Harriett should, as soon as she could hold a pen, make crude attempts in the same direction. She was furnished with a copy book in which she wrote slowly and laboriously; and she soon turned surreptitiously to the back of the book and werote loose rhymes that were jingling in her brain. On one occasion, the teacher passed by her desk when she was just finishing a rhymed account of some event which had occurred in the school room. Something must have attracted the teacher's attention; for he noticed her book, grabbed it, and, after running it through by himself, with a laugh, he proceeded to read it aloud to the school. When class was over, she scurried home. Thought her father soothed her ruffled mood, her copy-book confidences were discontinued.[2]

At the age of fourteen, her mother died and, as her father had in the same year been elected member of the Provincial Parliament, necessitating his presence in Quebec for a considerable portion of the year, the family was broken up. Her uncle, Timothy sent his son through Vermont and Canada to bring this niece to his home. Here and in the house of another uncle, Thomas Woolson, she spent the next four years, at Claremont, New Hampshire. At the close of this time, her father gathered his family together at a home in Oberlin, Ohio,[2] where he afterwards held offices of trust under the United States Government.[4]

Arey joined him at that town, and entered Oberlin College, class of 1837,[2] becoming one of the earliest young women who pursued a liberal course of education in a co-educational environment.[4] She was then at the head of her father's family and found it necessary to do much of her studying at night. When she neared the close of her junior year, her eyesight failed, and it was many years before she regained substantial use of her eyes.[2] In 1845, she received the degree of AB.[5]

Career

After a period of rest, she became a teacher in Cleveland, at first in the public schools, and afterwards in a ladies' school. She remained there until 1848 when she married Oliver Arey.[4][2] She began her literary career in Cleveland as a contributor to the Daily Herald of that city.[4]

After marriage, the couple moved to Buffalo, New York.[2] She had been, while a student, a writer for such literary papers as then flourished in Ohio and western New York, as well as for the New York Tribune, Willis & Morris's Home Journal, and the Philadelphia magazines, and this work was continued after her removal to Buffalo. In 1856, a volume of her poems was published by James Cephas Derby, New York. She was already engaged in editing a child's magazine, The Youth's Casket, and being subsequently invited to undertake another child's magazine of higher order, she declined, thinking that the demand for such publications was already supplied, But she suggested the starting of a magazine devoted to the interests of the household, in distinction from the fashion magazines then so popular. This was accordingly undertaken,[2] the Home Monthly with Abby Buchanan Longstreet (Mrs. C. H. Gildersleeve),[6] and was very cordially received. As far as known, this was the first publication in the country devoted to the interests of the home. After four or five years of this work, she was obliged, from failing health, to abandon it.[3] It was sold to a firm in Boston, coming under the editorship of the Rev, William Makepeace Thayer, with her name for two or three years more as associate editor.[2]

Not long after, her husband was called to the principalship of the State Normal School (now University at Albany, SUNY) in Albany, New York, which he held for two or three years. But, his health having been damaged by a protracted illness, he was obliged to give up for a time the duties of his position; and, through the year 1867, he took charge of the department of Natural Science in the Normal Cchool at Brockport, New York, while his wife held, at the same time, the position of lady-principal of the school. Her youngest child being then old enough to go with her into the school room, she had decided that in her husband's uncertain state of health her place was at his side. When, at the close of this year, he accepted the principalship of the second normal school of Wisconsin, (now University of Wisconsin–Whitewater), then about to be opened at Whitewater,[2] she took charge of the ladies' department in this school as "Preceptress and Teacher of English Literature, French, and Drawing".[7] The dedication of the new building at Whitewater had hardly taken place, when the sudden death of their only daughter gave the family a shock. The responsibilities of a large and constantly growing school left no time for literary effort,[2] but as the preceptress occupation suited her, for nine or ten years, she continued in the work.[3]

After nearly a decade in this field, she returned East, and, through the winter of 1876–7, was, with her husband, in charge of a ladies' school in Yonkers, New York, but in the following autumn, moved with her husband to Buffalo. A few years later, she found herself back in Cleveland, her husband having received a call to the charge of the normal school in that city.[2]

In 1884, Arey published a small volume entitled: "Home and School Training," (Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia), and soon after, undertook the editing of The Earnest Worker, the organ of the Women's Charitable Association of Cleveland.[2] Her principal writings were Household Songs and Other Poems (New York, 1854); and Home and School Training.[1]

Arey was one of the founders and first president of the Ohio Woman's State Press Association. For many years, she served as president of an active literary and social club.[1] She died April 26, 1901,[5] and was buried in Cleveland.[8]

Selected works

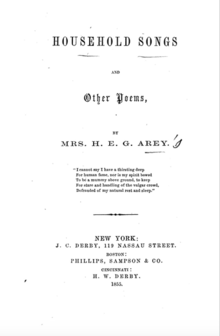

- 1855, Household songs, and other poems(Arey 1855, p. 1)

- 1884, Home and school training

- 1890, Myself

References

- Herringshaw 1904, p. 50.

- Wisconsin. State college, Whitewater 1893, p. 107.

- Willard & Livermore 1893, p. 32.

- Coggeshall 1860, p. 383.

- Coyle 1962, p. 17.

- Arey & Longstreet 1859, p. 1.

- Johannsen 1950, p. 22.

- "Died". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 26, 1901. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via newspapers.com.

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Bibliography

- Coyle, William (1962). Ohio Authors and Their Books: Biographical Data and Selective Bibliographies for Ohio Authors, Native and Resident, 1796-1950. World Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johannsen, Albert (1950). The House of Beadle and Adams and Its Dime and Nickel Novels: The Story of a Vanished Literature. University of Oklahoma Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)