Harold Weston

Harold Weston (February 14, 1894 - April 10, 1972) was an American modernist painter whose work ranged from realism to abstraction, as well as a highly regarded political activist.

Early life

Harold Weston was born February 14, 1894 in Merion, Pennsylvania, to S. Burns and Mary Hartshorne Weston. A twin brother, Edward, died at the age of six months. At the age of 15, Harold spent a year traveling in Europe and attending school in Switzerland and Germany. Harold Weston continued to paint and draw in his sketchbooks while in Europe.

After his return to the United States, Harold Weston was stricken by polio in 1911. His left leg was paralyzed. But Weston refused to believe doctors who declared that he would never walk again. Through a regime of physical conditioning and the use of leg braces and a cane, Weston learned how to walk (albeit with a pronounced limp). He even resumed hiking, clinging to trees as he went up and down mountains.

Weston entered Harvard University in 1912 and graduated magna cum laude with a degree in Fine Arts in 1916. Weston continued to hone his graphic art skills, serving as editor of the Harvard Lampoon and contributing a large number of original cartoons and artworks to the magazine. In 1914, he studied under the American painter Hamilton Easter Field at the Summer School of Graphic Arts in Ogunquit, Maine.

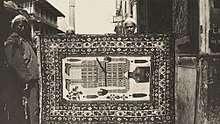

Unable to enlist due to his paralyzed leg and with World War I looming, Weston instead volunteered with the YMCA, serving as a hospitality liaison with the British Army in Baghdad in the Ottoman Empire. He encouraged soldiers to draw and paint to pass the time, and organized Baghdad Art Club in 1917 as a means of exhibiting and promoting their art. Because of this work, he was appointed Official Painter for the British Army in 1918.

Main period of work

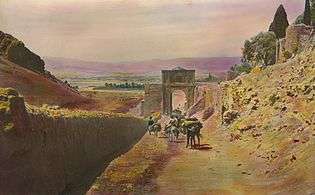

Weston's sojourn in the Middle East proved to have a lasting impact on both his art and social activism. The colors and light he witnessed there deeply affected his palette.

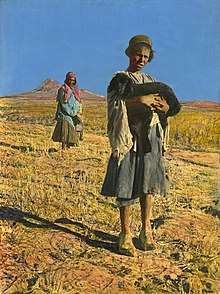

Weston also witnessed the horror of famine and disease while in the Middle East. He saw men, women, and children die of heat exhaustion and starvation.

Weston returned to the United States after the war via the Far East. For four months, he lived in a tiny one-room apartment in New York City, working in exchange for rent. He explored the city's art galleries, becoming acquainted with the latest in modern art reaching American shores.

Adirondack works

Weston decided to leave the city for the Adirondack Mountains, where he had spent summers as a child. In 1920, with the help of some local carpenters, he built a one-room log cabin near St. Huberts, New York. Throughout 1921 and the winter of 1922, he painted and sketched in charcoal, pencil, and oils on cardboard and canvas.

Weston's first solo exhibition of his work was at the Montross Gallery in New York City. Over one hundred oil sketches and 63 oil paintings on canvas were shown in November 1922. The show was a huge success. Critics heaped praise on his vibrant use of color and the unique American perspective he brought to his work.

Weston met Faith Borton in early 1922 when he invited his sister and some of her Vassar College friends to his cabin that winter. Faith impressed him with her ability to withstand the harsh winter weather, her intelligence, and her sensitivity. The couple was married on May 12, 1923.

Over the next two years, Harold and Faith Weston lived in the cabin in the Adirondack Mountains.

'Landscape nudes'

The period produced a significant change in Weston's work. Weston turned his attention away from landscapes and to the nude. The paintings Harold Weston produced came to be known as 'landscape nudes'—a radical departure from traditional nudes.

Alfred Stieglitz considered the nudes daring and new, but the Montross Gallery refused to show them.

In August 1925, Harold Weston collapsed from a kidney infection. Doctors removed one of his kidneys, but an infection set in. He was near death for nearly a month before he began to recover. Doctors advised him to move to a warmer clime, but the Westons decamped instead for a farmhouse near Céret in the French Pyrenees. The house they lived in was centuries old, and built into a hillside. A working sheep barn below the living quarters helped keep it warm in winter. A chapel to one side held services every day, the bell in the tower over their rooms ringing the faithful to worship.

European influences

Europe made Weston's palette lighter. He and Faith made side-trips to Paris, France and became acquainted with painters working there. Captivated by etching, Weston learned the technique and began to experiment with it. He also created the "Love Series."

Weston exhibited his work in Paris, and continued to show at the Montross Gallery.

The Westons—now with two small children in tow—returned to America in 1930. They took up residence for a short period in Greenwich Village before returning to the cabin in the mountains near St. Huberts.

Toward domesticity and realism

Weston continued to turn out prodigious amounts of artwork. With a small family surrounding him, he focused more and more on the everyday: A quilt, plants in the garden, snowshoes. His work was displayed at the Phillips Memorial Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art. His painting Green Hat won third prize in painting at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939.

During the Great Depression Weston was asked by the Treasury Relief Art Project to paint murals for the General Services Administration building in Washington, D.C.. Over the next two years, Weston worked 11 hours a day creating the 22 panels on canvas.

Political work

The advent of World War II led Weston to abandon painting entirely in 1942 in favor of political work. Disturbed by memories of the starvation he had seen in the Middle East, he lobbied full-time for humanitarian food relief. In 1943, he founded Food for Freedom, and built a coalition of civic, religious, labor and farm organizations representing more than 60 million Americans which advocated for food aid for refugees in Europe and Asia. He became an expert on food policy and the politics of farm policy in the U.S.

Weston conceived of an international food relief agency which would provide a permanent mechanism for supplying food to refugees around the globe. He personally lobbied Eleanor Roosevelt for the idea; she credited him as the impetus behind the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

After seven years, exhausted from his political endeavors and wishing to return to painting, Weston seized upon the idea of painting the United Nations headquarters under construction in New York City. He worked on the painting series for three years, further refining his hyper-realistic style.

In 1954, the Westons started renting a slum-like flat in Greenwich Village.

That same year, Weston helped found the National Council on Arts and Government, an artists' group which lobbied for government support for the arts. He later served as its vice president and president. In 1965, the group won passage of legislation creating the National Endowment for the Arts.

He also joined the International Association of Plastic Arts (later the International Association of Arts [IAA]) in 1954, and served as its United States Committee president from 1961 to 1967.

Later life

Known more for his political work than his painting by his mid-60s, Weston nevertheless continued to paint. He abandoned realism, experimenting with abstraction. He found inspiration on a trip to the Isle of Rhodes in Greece. In nature, Weston saw the pattern and rhythm which he could transfer to canvas. He painted his last significant work, the 'Stone Series,' from 1968 to 1972. It was based on stones found on the Gaspé Peninsula in Canada.

In 1971, Harold Weston published Freedom in the Wilds: A Saga of the Adirondacks.

Harold Weston died on April 10, 1972 in New York City.

References

- Weston, Harold. Freedom in the Wilds: An Artist in the Adirondacks. Third edition, containing Weston's Letters and Diaries, edited by Rebecca Foster. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

- Appelhof, Ruth A.; Haskell, Barbara; and Hayes, Jeffrey R., editors. The Expressionist Landscape: North American Modernist Painting 1920–1947. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988. ISBN 0-295-96691-2

- Foster, Rebecca; Welsh, Caroline; and Stebbins Jr., Theodore E. Wild Exuberance: Harold Weston's Adirondack Art. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8156-0834-9

- Phillips, Stephen B. Twentieth-Century Still-Life Painting from the Phillips Collection. Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 1997. ISBN 0-943044-22-7

- Weston, Harold. Freedom in the Wilds: A Saga of the Adirondacks. St. Huberts, N.Y.: Adirondack Trail Improvement Society, 1971.

- Wolf, Ben. Harold Weston. Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press, 1978.