Harold Moody

Harold Arundel Moody[1] (8 October 1882 – 24 April 1947) was a Jamaican-born physician in London who campaigned against racial prejudice and established the League of Coloured Peoples in 1931 with the support of the Quakers.

Harold Moody | |

|---|---|

| Born | Harold Arundel Moody 8 October 1882 Kingston, Jamaica |

| Died | 24 April 1947 (aged 64) Peckham, London, England |

| Alma mater | King's College London |

| Occupation | Physician, civil rights activist |

| Known for | Founder of the League of Coloured Peoples |

| Spouse(s) | Olive Mable Tranter |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | Ludlow Moody (brother); Ronald Moody (brother) |

Biography

Moody was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1882, the son of pharmacist Charles Ernest Moody and his wife Christina Emmeline Ellis.[2] In 1904, he sailed to the United Kingdom to study medicine at King's College London, finishing top of his class when he qualified in 1910, aged 28.[3] Having been refused work because of his colour, he started his own medical practice in Peckham, south-east London, in February 1913 .[2][4]

In March 1931 Harold Moody formed and became president of the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP), which was concerned with racial equality and civil rights in Britain and elsewhere in the world. Its first members included C. L. R. James, Jomo Kenyatta, Una Marson, and Paul Robeson.[3]

He also campaigned against racial prejudice in the armed forces, and is credited with overturning the Special Restriction Order (or Coloured Seamen's Act) of 1925, a discriminatory measure that sought to provide subsidies to merchant shipping employing only British nationals and required alien seamen (many of whom had served the United Kingdom during the First World War) to register with their local police. Many black and Asian British nationals had no proof of identity and were made redundant. In 1933 he became involved in the Coloured Men's Institute, founded by Kamal Chunchie as a religious, social and welfare centre for sailors.[2]

A devout Christian, Moody was active in the Congregational Union, the Colonial Missionary Society (of which he became chair of the board of directors in 1921) and later was appointed president of the Christian Endeavour Union (1936).[2][5]

Having become a respected and influential doctor in Peckham, Moody was very involved in organising the local community during the Second World War.[6] Historian Stephen Bourne has noted: "In 1944 there was a terrible bombing in south London and he was the first doctor on the scene. He played an important role in these events, saving many lives. Yet this wartime history is not known."[6]

In the last months of his life he undertook a speaking tour of tour of North American states, and subsequently died at his home in Queen's Road, Peckham, in 1947, aged 64, after contracting influenza.[3]

Family life

In 1913, Moody married Olive Mable Tranter, a white nurse with whom he worked at the Royal Eye Hospital in London, and they had six children.[7]

His brother Ludlow also studied medicine in London and won the Huxley Prize for physiology at King's College. Ludlow married Vera Manley and both returned to the Caribbean. Another brother was the sculptor Ronald Moody. Charles Arundel Moody, Harold's son, became in 1940 the second black commissioned officer in the British Army, rising to the rank of colonel.[8]

Legacy

The book Negro Victory: The life story of Dr. Harold Moody, by David A. Vaughan, was published in 1950.[1]

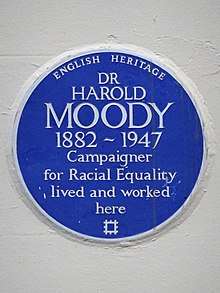

The house where Moody lived at 164 Queen's Road, Peckham, now has a blue plaque dedicated to him that was erected in 1995 by English Heritage.[9][10]

The National Portrait Gallery, London, has a bronze bust of Moody, cast in 1946 by his brother Ronald (1900–1984).[11]

A short silent animation (by Jason Young) about his married life was produced in 1998, entitled The Story of Dr. Harold Moody.[12]

Dr Harold Moody Park in Nunhead was officially opened in 1999.[13]

Moody is named on the list of "100 Great Black Britons".[14]

On 13 March 2019, a Nubian Jak Community Trust commemorative blue plaque was unveiled outside the YMCA Club at Tottenham Court Road, where the League of Coloured Peoples was founded at a meeting 88 years earlier.[15][16]

References

- David A. Vaughan, Negro Victory: The Life Story of Dr Harold Moody, London: Independent Press, 1950.

- "Harold Moody", Making Britain, The Open University.

- "Dr Harold Moody, the Peckham physician who ought to be thought of as Britain's Martin Luther King'", Southwark News, 26 October 2017.

- John Simkin, "Harold Moody", Spartacus Educational.

- "Dr Harold Moody, 1882–1947", African Stories in Hull & East Yorkshire.

- Dominic Casciani, "Hidden tales of the black home front", BBC News, 5 October 2002.

- "Harold Moody", Making Britain, The Open University.

- "Dr. Harold Moody", Imperial War Museum.

- "Harold Moody blue plaque in London", Blue Plaque Places.

- "Moody, Dr Harold (1882–1947)", English Heritage.

- "Harold Moody – National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "The Story of Dr. Harold Moody (1998)", IMDb.

- John D. Beasley, "New Park", Peckham & Nunhead Through Time, Amberley Publishing Limited, 2009.

- "Harold Moody", 100 Great Black Britons.

- Claire.Gilderson, "First British Civil Rights Movement founded at YMCA Club", YMCA Club, 11 March 2019.

- "Blue Plaque for Dr Harold Moody", The Weekly Gleaner, 14–20 March 2019.

External links

- "Harold Moody", Making Britain, The Open University.

- "Black History Month 2018: Harold Moody", SOAS Archives and Special Collections, 26 October 2018.

- "Harold Moody", Spartacus Educational.

- "Harold Moody British Civil Rights Leader 1930's" on YouTube.