Harold Innis and the fur trade

Harold Adams Innis (November 5, 1894 – November 8, 1952) was a professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on Canadian economic history and on media and communication theory. He helped develop the staples thesis which holds that Canada's culture, political history and economy have been decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of staples such as fur, fish, wood, wheat, mined metals and fossil fuels.

Harold Innis's classic study The Fur Trade in Canada (1930) draws sweeping conclusions about the complex and frequently devastating effects of the fur trade on aboriginal peoples; about how furs as staple products induced an enduring economic dependence among the European immigrants who settled in the new colony and about how the fur trade ultimately shaped Canada's political destiny.[1]

The Fur Trade in Canada

Introduction

Harold Innis begins The Fur Trade in Canada with a brief chapter on the beaver which became a much desired fur due to the popularity of the beaver hat in European society.[2] He remarks that it is impossible to understand the developments of the fur trade, or of Canadian history, without some knowledge of the beaver's life and habits.[3] Biographer John Watson notes that Innis was following an analytical approach he had learned during his post-graduate work at the University of Chicago. In such case studies, Innis had been taught it was necessary to understand the nature of a commodity or staple product and to adopt a comprehensive view of it by studying its geography.[4] Since First Nations cultures and ways of life are intrinsically tied to landscape, it was their techniques of hunting and preparation, coupled with geography that essentially determined the development of the fur trade [5] In the case of the beaver the techniques for creating the best quality of beaver pelt hats included the age of the animal and what time of year the beaver was killed.[5]

Thus, Innis notes that the most valuable beaver fur was to be found north of the St. Lawrence River especially in the deciduous forests of the Pre-Cambrian Shield with its abundance of waterways. He suggests that beaver fur could be carried long distances because the pelt of the average adult weighed less than two pounds. The animal itself was a good source of food.

Innis points out that the beaver "migrates very little and travels over land very slowly." Although beavers reproduce prolifically, it takes them more than two years to mature. These biological characteristics made their destruction in great numbers inevitable, especially after Indian hunters acquired European axes that could chop through beaver lodges and dams. European guns, knives and spears also made the sedentary beaver easy prey.[6]

Innis concludes his introduction by noting that as beaver populations were destroyed in eastern areas, traders were forced to push north and west in search of new sources of supply. "The problem of the fur trade," he writes, "became one of organizing the transport of supplies and furs over increasingly greater distances. In this movement, the waterways of the beaver areas were of primary importance and occupied a vital position in the economic development of northern North America."[7]

Fur trade history

Harold Innis meticulously traces the fur trade over more than four centuries, from the early 16th century to the 1920s. It is a story filled with military conflict between French and English imperial forces and among warring Indian tribes. It is also a tale of shrewd barter and commercial rivalry. Yet Innis, the economic historian, tells the story in 400 pages of dry, Euro-centric and dense prose packed with statistics.[8]

Innis begins by chronicling the first contacts between European fishing fleets and eastern native tribes in the early 16th century.[9] After the founding of the French settlement at Quebec in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain, the colony known as New France depended on furs for its economic survival. Champlain joined forces with the Huron Confederacy and its tribal allies against the Iroquois Confederacy in the long struggle to control the fur trade.[10]

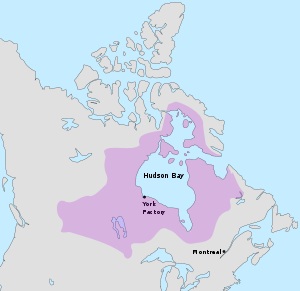

As New France grew, French colonists, first known as coureurs de bois and later voyageurs, travelled north and west from Montreal in search of new supplies while their British rivals set up northern trading posts run by the Hudson's Bay Company. The commercial rivalry continued after the British Conquest of New France in 1759, with the establishment of the North West Company by a group of bilingual Scottish Gaelic/English-speaking Montreal merchants who had come to British North America from the Scottish Highlands in the wake of the defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden and the incipient beginnings of the Highland Clearances. The two companies built trading posts far west of Lake Superior and Hudson Bay, but the Nor'Westers were more aggressive as they travelled north to the Arctic Ocean via the Mackenzie River and west to the Pacific. The fierce competition ended in 1821 with the amalgamation of the companies into a Hudson's Bay Company monopoly. The Company finally surrendered its northwestern empire when it sold its land to Canada in 1869 following the decrease in profits and demand for furs.[11]

Innis rounds out the story by documenting the decline of the fur trade monopoly as silk hats and fancier fox fur displaced beaver. The coming of steam boats to the West and the building of railways brought increasing competition from independent traders and new companies from the American West as well as firms from Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver. Improved transportation also brought increased control of the trade and cheaper goods. Increased control led to more inspections, better accounting, conservative policies, decreased aggression, and expansion of districts. Problems that arose included the difficulty in monitoring large districts and policies that were sometimes too rigid. The increase in agriculture also brought competition through decreased reliance on game for food.[12] Innis ends by noting that in 1927 the Hudson's Bay Company announced it had invested in two fox farms in Prince Edward Island making the outlook for the trade in wild fur increasingly uncertain. "The time would appear to have arrived," Innis writes, "for a competent survey of the problems of the trade looking to the conservation of one of Canada's important natural resources."[13] Indeed, in the end there was an abundance of goods and a lack of furs, suggesting the trade was no longer a major part of the economy.[14]

Furs, culture and technology

Innis's account of the fur trade as "the history of contact between two civilizations, the European and the North American," focuses on the radical effects of new techniques and technologies.[15] The trade became important in the late 16th century when the beaver hat, a new style of waterproof headgear, became popular among well-dressed European gentlemen.[16] Innis stresses however, that the trade was propelled by native people's intense demand for European manufactured goods:

The importance of iron to a culture dependent on bone, wood, bark and stone can only be suggested. The cumbersome method of cooking in wooden vessels with heated stones was displaced by portable kettles. Work could be carried out with greater effectiveness with iron axes and hatchets, and sewing became much less difficult with awls than it had been with bone needles. To the Indians, iron and iron manufactures were of prime importance. The French were the gens du fer.[17]

Muskets, knives and metal spears also made hunting easier and more efficient, but Innis points out that the convenience of European manufactured goods came at a high price. The native peoples became dependent on European traders for fresh supplies, ammunition and spare parts. More efficient hunting with guns led to the extermination of the beaver and the need to push into new hunting territories in search of more furs. This competition led to outbreaks of fighting. "Wars between tribes which with bows and arrows had not been strenuous," Innis writes, "conducted with guns were disastrous."[18] Everything was made worse because native peoples had no immunity to European diseases such as smallpox which continually ravaged their communities, decimating whole populations.[19] Finally, European rum, brandy and strong wine brought illness, conflict and addiction.[20]

Again and again, Innis draws attention to what he sees as the disastrous and catastrophic effects of the contact between a more technologically advanced European civilization and traditional native societies. He writes that the aboriginal peoples' dependence on the trade in beaver pelts to secure European iron goods "disturbed the balance which had grown up previous to the coming of the European."[21] Decades later, Innis would return to this concept of balance in his communications writings.[22]

Just as aboriginal peoples depended on imported manufactured goods, European traders relied for their survival on native tools and techniques. Birch-bark canoes enabled traders to travel in spring, summer and fall; snowshoes and toboggans made winter travel possible; while Indian corn, pemmican and wild game provided sustenance and clothing. Equally important, Innis notes, was the natives' thorough knowledge of woodland territories and the habits of the animals they hunted.[23]

Biographer John Watson argues that in his study of the fur trade, Innis broke new ground by making cultural factors central to economic development. In Watson's terms, The Fur Trade in Canada is a "complex analysis" of three distinct cultural groups: metropolitan European customers who bought expensive beaver hats, colonial settlers who traded beaver fur for goods from their home countries and indigenous peoples who came to depend on European iron-age technologies.[24] Also, Innis notes the dependence of traders on First Nations peoples,[25] and suggests their dominance in early trading when he writes, "The trade in furs was stimulated by French traders who rapidly acquired an intimate knowledge of the Indian's language, customs, and habits of life" [25]

The trader encouraged the best hunters, exhorted the Indians to hunt beaver, and directed their fleets of canoes to the rendezvous. Alliances were formed and wars were favoured to increase the supply of fur. Goods were traded that would encourage the Indian to hunt beaver.[25]

Innis writes that the French used Christianity to make First Nations more amenable to trade. They encouraged war or promoted peace as ways of winning First Nations support. He notes these policies led to an increase in the overhead costs of trade that decreased profits and encouraged the growth of monopolies.[26]

Economic effects of staple products

Canada as a "marginal" colony

Innis's 15-page conclusion to the Fur Trade in Canada explains the significance of staple products, such as furs, to colonial development. It also explores the effects of the staples trade on the more technologically advanced home countries of France and Britain. "Fundamentally the civilization of North America is the civilization of Europe," Innis writes, "and the interest of this volume is primarily in the effects of a vast new land area on European civilization."[27] He notes that European settlers in North America survived by borrowing the cultural traits of the indigenous peoples, but also sought to maintain European standards of living by exporting goods not available in the home country in exchange for manufactured products. In Canada's case, the first such goods were the staples cod fish and beaver fur. Later staples included lumber, pulp and paper, wheat, gold, nickel and other metals.[28]

Innis maintains that this two-way trade had significant effects. The colony put its energies into producing staples while the mother country manufactured finished products. Thus, the staples trade promoted industrial development in Europe, while the colony remained tied to the production of raw materials. As time passed, colonial agriculture, industry, transportation, trade, finance and government activities tended to be subordinated to the production of staple commodities for industrial Britain, and later for the rapidly developing United States. This cumulative dependence on staples relegated Canadians to the status of hewers of wood and drawers of water.[29]

"The economic history of Canada has been dominated by the discrepancy between the centre and margin of Western civilization," Innis concludes.[30] For him, as biographer Donald Creighton points out, Canada's economic axis began as "a great competitive east-west trading system, founded on the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, one end of which lay in the metropolitan centres of western Europe and the other in the hinterland of North America. It was a transoceanic as well as a transcontinental system."[31]

Concept of "cyclonics"

Innis argued that a country dependent on the export of staple products would always be vulnerable both to disruptions in the sources of supply and to the whims of export markets. In the case of beaver fur, for example, a slight change in fashion in sophisticated metropolitan centres like London and Paris could have devastating effects in a marginal "backwoods" colony dependent on exporting staples. Innis developed the concept of "cyclonics" to explain the disruptions that occurred when new technologies led to the rapid exploitation and then exhaustion of staple commodities.[32] European-made guns, for example, increased the efficiency of beaver hunting, but led to the animal's rapid extermination forcing traders into costly, long-distance searches for new sources of supply. Later, the decline of the white pine, a vital commodity in the lumber trade, forced the shift to pulp and paper production based on abundant spruce.[33]

Shifts from one staple to another led to constant economic cyclones. "Canadians have exhausted their energies," Innis wrote in 1929, "in opening up the West, in developing mines, hydro-electric power and pulp and paper mills of the Canadian Shield, in building transcontinental railways, grain elevators and cities."[34]

For Innis, imported industrial techniques led to rapid resource exploitation, overproduction, waste, depletion and economic collapse. These were the problems of economically marginal, staples-producing countries like Canada.[35]

Politics and the staples trade

Innis famously writes that Canada "emerged not in spite of geography but because of it." The country's boundaries roughly coincide, he argues, with the fur-trading areas of northern North America.[36] Certainly the increased demand for furs, such as beaver, resulted in increased exploration westward. Innis maintains that the shift from furs to lumber led to European immigration and the rapid settling of the West. The "coffin ships" that carried the lumber to Europe brought back emigrants as a "return cargo." The export of lumber, and later wheat, required improvements in transportation --- the construction of canals and the building of railways. The costs of these transportation improvements were largely responsible, he writes, for the Act of Union joining Upper and Lower Canada in 1840-41, and the political Confederation of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in 1867.[37] Economic reliance on staples production in a vast country led to the development of centralized banking, a strong federal government, and "the combination of government ownership and private enterprise which has been a further characteristic of Canadian development."[38] Through the encouragement of the monopoly of the Hudson's Bay Company is born centralized control, use of military aggression, and hints of nationalism .[39] Innis concludes that the maintenance of ties with France and Britain encouraged a diversity of institutions and greater tolerance adding that "Canada has remained fundamentally a product of Europe."[40]

Assessment

Historian Carl Berger notes that it took 15 years to sell the first thousand copies of The Fur Trade in Canada. Yet, he writes, the book is one of the few in Canadian historical literature that deserves to be described as seminal. According to Berger, Innis showed that Canada was far from "a fragile political creation and that its existence represented the triumph of human will and determination." He replaced this "old and familiar truism" with the idea that river systems and the Canadian Shield imposed a geographic unity and that "Confederation was, in a sense, a political reflection of the natural coherence of northern America." Berger adds that, in exploring the links between economic changes and political developments, "Innis's insights pointed to a general reinterpretation of Canadian history." Innis also "placed Indian culture at the centre of his study of the fur trade and was the first to explain adequately the disintegration of native society under the thrust of European capitalism."[41] Unlike other historians, Innis emphasized the contributions of First Nations peoples.[42] "We have not yet realized," he writes, "that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions."[43]

Berger refers to the "sense of fatalism and determinism in Innis's economic history" adding that for Innis, material realities determined history, not language, religion or social beliefs. "His history, as history, was dehumanized," Berger adds.[44]

Biographer John Watson argues however, that The Fur Trade in Canada is "more complex, more universal, and less rigidly deterministic than commonly accepted." Watson points for example, to Innis's central concern with the role of culture in economic history and his awareness of cultural disintegration under the impact of advanced technologies. "Innis never uses the staple as anything more than a focusing point around which to examine the interplay of cultures and empires," he writes.[45]

Notes

- Innis, Harold. (1977) The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. Revised and reprinted. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp.386-392.

- Innis (Fur Trade) p. 13

- Innis (Fur Trade) p.3.

- Watson, Alexander, John. (2006). Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p.147.

- Innis (Fur Trade) p. 14

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp. 3-6.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.6.

- Vancouver Public Library. Great Canadian Books of the Century. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, p.40. The authors note that "Innis was not the most elegant of writers—his prose is often swamped with unnecessary detail."

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.9-12.

- Moore, Christopher. (1987) "Colonization and Conflict: New France and its Rivals 1600-1760." In The Illustrated History of Canada, edited by Craig Brown. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys Ltd., pp.107-115.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.43-338.

- Innis (Fur Trade) P. 320-365

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.341-379. The quotation appears on p.379.

- Innis (Fur Trade) p. 373-4

- Innis, pp. 388–389.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 12.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 18.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 20.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 21.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 19. Also see, Ray, Arthur. "When Two Worlds Met" in The Illustrated History of Canada, edited by Craig Brown. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, p. 88: "Since alcohol was cheap to obtain, could be consumed on the spot, and was addictive, the European traders had very strong economic incentives to trade and give away large quantities of liquor."

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 388.

- Innis mentions the native peoples specifically in his essay "Industrialism and Cultural Values." In The Bias of Communication. (1951) Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 141.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p. 13.

- Watson p. 152.

- Innis (Fur Trade) p. 16

- Innis (Fur Trade), pp. 30–31

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.383.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.383-385.

- Innis (Fur Trade) pp.384-386.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.385.

- Creighton, Donald. (1957). Harold Adams Innis: Portrait of a Scholar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p.105.

- Watson, p.89.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.396.

- Innis, "notes and comments," quoted in Watson, p.162.

- Watson, p.160.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.392-393.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.394-397.

- Innis, (Fur Trade) pp.396 & 401.

- Innis (Fur Trade) p. 32-51

- Innis, (Fur Trade) p.401.

- Berger, Carl. (1976). "Harold Innis: The Search for Limits." In The Writing of Canadian History. Toronto: Oxford University Press, pp.97-100.

- Dickason, Olive; McNab, David. (2009). Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples From Earliest Times. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, p.ix

- Innis (Fur Trade), p.392.

- Berger, pp.97-98.

- Watson, pp.148-149.