Harmonics (electrical power)

In an electric power system, a harmonic is a voltage or current at a multiple of the fundamental frequency of the system, produced by the action of non-linear loads such as rectifiers, discharge lighting, or saturated magnetic devices. Harmonic frequencies in the power grid are a frequent cause of power quality problems. Harmonics in power systems result in increased heating in the equipment and conductors, misfiring in variable speed drives, and torque pulsations in motors.

Current harmonics

In a normal alternating current power system, the current varies sinusoidally at a specific frequency, usually 50 Hz or 60 Hz hertz. When a linear electrical load is connected to the system, it draws a sinusoidal current at the same frequency as the voltage (though usually not in phase with the voltage).

Current harmonics are caused by non-linear loads. When a non-linear load, such as a rectifier is connected to the system, it draws a current that is not necessarily sinusoidal. The current waveform distortion can be quite complex, depending on the type of load and its interaction with other components of the system. Regardless of how complex the current waveform becomes, the Fourier series transform makes it is possible to deconstruct the complex waveform into a series of simple sinusoids, which start at the power system fundamental frequency and occur at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

Further examples of non-linear loads include common office equipment such as computers and printers, Fluorescent lighting, battery chargers and also variable-speed drives.

In power systems, harmonics are defined as positive integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. Thus, the third harmonic is the third multiple of the fundamental frequency.

Harmonics in power systems are generated by non-linear loads. Semiconductor devices like transistors, IGBTs, MOSFETS, diodes etc are all non-linear loads. Further examples of non-linear loads include common office equipment such as computers and printers, Fluorescent lighting, battery chargers and also variable-speed drives. Electric motors do not normally contribute significantly to harmonic generation. Both motors and transformers will however create harmonics when they are over-fluxed or saturated.

Non-linear load currents create distortion in the pure sinusoidal voltage waveform supplied by the utility, and this may result in resonance. The even harmonics do not normally exist in power system due to symmetry between the positive- and negative- halves of a cycle. Further, if the waveforms of the three phases are symmetrical, the harmonic multiples of three are suppressed by delta (Δ) connection of transformers and motors as described below.

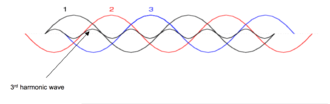

If we focus for example on only the third harmonic, we can see how all harmonics with a multiple of three behaves in powers systems.[1]

Power is supplied by a three phase system, where each phase is 120 degrees apart. This is done for two reasons: mainly because three-phase generators and motors are simpler to construct due to constant torque developed across the three phase phases; and secondly, if the three phases are balanced, they sum to zero, and the size of neutral conductors can be reduced or even omitted in some cases. Both these measures results in significant costs savings to utility companies. However, the balanced third harmonic current will not add to zero in the neutral. As seen in the figure, the 3rd harmonic will add constructively across the three phases. This leads to a current in the neutral wire at three times the fundamental frequency, which can cause problems if the system is not designed for it, (i.e. conductors sized only for normal operation.)[1] To reduce the effect of the third order harmonics delta connections are used as attenuators, or third harmonic shorts as the current circulates in the delta the connection instead of flowing in the neutral of a wye connection.

Voltage harmonics

Voltage harmonics are mostly caused by current harmonics. The voltage provided by the voltage source will be distorted by current harmonics due to source impedance. If the source impedance of the voltage source is small, current harmonics will cause only small voltage harmonics. It is typically the case that voltage harmonics are indeed small compared to current harmonics. For that reason, the voltage waveform can usually be approximated by the fundamental frequency of voltage. If this approximation is used, current harmonics produce no effect on the real power transferred to the load. An intuitive way to see this comes from sketching the voltage wave at fundamental frequency and overlaying a current harmonic with no phase shift (in order to more easily observe the following phenomenon). What can be observed is that for every period of voltage, there is equal area above the horizontal axis and below the current harmonic wave as there is below the axis and above the current harmonic wave. This means that the average real power contributed by current harmonics is equal to zero. However, if higher harmonics of voltage are considered, then current harmonics do make a contribution to the real power transferred to the load.

Total harmonic distortion

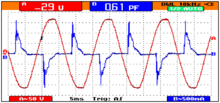

Total harmonic distortion, or THD is a common measurement of the level of harmonic distortion present in power systems. THD can be related to either current harmonics or voltage harmonics, and it is defined as the ratio of total harmonics to the value at fundamental frequency times 100%.

where Vk is the RMS voltage of kth harmonic, Ik is the RMS current of the kth harmonic, and k = 1 is the fundamental frequency.

It is usually the case that we neglect higher voltage harmonics; however, if we do not neglect them, real power transferred to the load is affected by harmonics. Average real power can be found by adding the product of voltage and current (and power factor, denoted by pf here) at each higher frequency to the product of voltage and current at the fundamental frequency, or

where Vk and Ik are the RMS voltage and current magnitudes at harmonic k ( denotes the fundamental frequency), and is the conventional definition of power without factoring in harmonic components.

The power factor mentioned above is the displacement power factor. There is another power factor that depends on THD. True power factor can be taken to mean the ratio between average real power and the magnitude of RMS voltage and current, .[2]

and

Substituting this in for the equation for true power factor, it becomes clear that the quantity can be taken to have two components, one of which is the traditional power factor (neglecting the influence of harmonics) and one of which is the harmonics’ contribution to power factor:

Names are assigned to the two distinct factors as follows:

where is the displacement power factor and is the distortion power factor (i.e. the harmonics' contribution to total power factor).

Effects

One of the major effects of power system harmonics is to increase the current in the system. This is particularly the case for the third harmonic, which causes a sharp increase in the zero sequence current, and therefore increases the current in the neutral conductor. This effect can require special consideration in the design of an electric system to serve non-linear loads.[3]

In addition to the increased line current, different pieces of electrical equipment can suffer effects from harmonics on the power system.

Motors

Electric motors experience losses due to hysteresis and eddy currents set up in the iron core of the motor. These are proportional to the frequency of the current. Since the harmonics are at higher frequencies, they produce higher core losses in a motor than the power frequency would. This results in increased heating of the motor core, which (if excessive) can shorten the life of the motor. The 5th harmonic causes a CEMF (counter electromotive force) in large motors which acts in the opposite direction of rotation. The CEMF is not large enough to counteract the rotation; however it does play a small role in the resulting rotating speed of the motor.

Telephones

In the United States, common telephone lines are designed to transmit frequencies between 300 and 3400 Hz. Since electric power in the United States is distributed at 60 Hz, it normally does not interfere with telephone communications because its frequency is too low.

Sources

A pure sinusoidal voltage is a conceptual quantity produced by an ideal AC generator built with finely distributed stator and field windings that operate in a uniform magnetic field. Since neither the winding distribution nor the magnetic field are uniform in a working AC machine, voltage waveform distortions are created, and the voltage-time relationship deviates from the pure sine function. The distortion at the point of generation is very small (about 1% to 2%), but nonetheless it exists. Because this is a deviation from a pure sine wave, the deviation is in the form of a periodic function, and by definition, the voltage distortion contains harmonics.

When a sinusoidal voltage is applied to a linear load, such as a heating element, the current through it is also sinusoidal. In non-linear loads, such as an amplifier with a clipping distortion, the voltage swing of the applied sinusoid is limited and the pure tone is polluted with a plethora of harmonics.

When there is significant impedance in the path from the power source to a nonlinear load, these current distortions will also produce distortions in the voltage waveform at the load. However, in most cases where the power delivery system is functioning correctly under normal conditions, the voltage distortions will be quite small and can usually be ignored.

Waveform distortion can be mathematically analysed to show that it is equivalent to superimposing additional frequency components onto a pure sinewave. These frequencies are harmonics (integer multiples) of the fundamental frequency, and can sometimes propagate outwards from nonlinear loads, causing problems elsewhere on the power system.

The classic example of a non-linear load is a rectifier with a capacitor input filter, where the rectifier diode only allows current to pass to the load during the time that the applied voltage exceeds the voltage stored in the capacitor, which might be a relatively small portion of the incoming voltage cycle.

Other examples of nonlinear loads are battery chargers, electronic ballasts, variable frequency drives, and switching mode power supplies.

See also

Further reading

- Sankaran, C. (1999-10-01). "Effects of Harmonics on Power Systems". Electrical Construction and Maintenance Magazine. Penton Media, Inc. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

References

- "Harmonics Made Simple". ecmweb.com. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- W. Mack Grady and Robert Gilleski. "Harmonics and How They Relate to Power Factor" (PDF). Proc. of the EPRI Power Quality Issues & Opportunities Conference.

- For example, see the National Electrical Code: "A 3-phase, 4-wire, wye-connected power system used to supply power to nonlinear loads may necessitate that the power system design allow for the possibility of high harmonic neutral currents. (Article 220.61(C), FPN No. 2)"