Hardhead catfish

The hardhead catfish (Ariopsis felis) is a species of sea catfish from the northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, and similar to the gafftopsail catfish (Bagre marinus). It is one of four species in the genus Ariopsis.[3] The common name, hardhead catfish, is derived from the presence of a hard, bony plate extending rearward toward the dorsal fin from a line between the catfish's eyes.[4] It is an elongated marine catfish that reaches up to 28 in (70 cm) in length and 12 lb (5.5 kg) in weight.[5] Their typical weight is less than 1 lb (450 g), but they commonly reach up to 3 lb (1.4 kg). They are often a dirty gray color on top, with white undersides.

| Hardhead catfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Ariidae |

| Genus: | Ariopsis |

| Species: | A. felis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ariopsis felis (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Habits, distribution, and characteristics

Hardhead catfish are found mostly in the near-shore waters of the Western Atlantic Ocean, around the southeast coast of the United States, around the Florida Keys and the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.[4][5] Hardhead catfish are also found in brackish estuaries and river mouths where the bottom is sandy or muddy,[6] but only occasionally enter freshwater.[1] It tends to move from shallower to deeper waters in the winter months.[7] The species is generally common to abundant within its range.[1]

The hardhead catfish has four barbels under the chin, with two more at the corners of the mouth.[8] These barbels help the catfish find crabs, fish, and shrimp in the muddy bays where they live. The dorsal and pectoral fins each are supported by a sharp, slime-covered, barbed spine. The dorsal spine is normally erect when the fish is excited and a tennis shoe or even a leather-soled shoe offers little protection. The gafftopsail catfish looks similar to the hardhead catfish, but its dorsal and pectoral spines have a distinctive fleshy extension (like the fore-and-aft topsail of a ship).

Feeding behavior

A. felis consumes a wide range of food. It is an opportunistic consumer that uses mud and sand flats as hunting grounds.[8] It is also mainly a secondary consumer, ingesting primarily detritus, meio-, and macrobenthic fauna, and fish. Its diet primarily consists of algae, seagrasses, cnidarians, sea cucumbers, gastropods, polychaetes, shrimp, and crabs. It can occasionally be a tertiary consumer.[8]

Its diet depends on its size and location. Younger hardhead catfish tend to eat small crustaceans, like amphipods, shrimp, blue crabs, mollusks, and annelids.[9] Juveniles that are still under the protection of the male mouthbrooder feed predominately on planktonic crustaceans close by to the mouth of the parent.[8] The adults primarily consume larger fish.[9]

Locomotion

Significant evidence suggests correlation between the fish's activity patterns and seasonal changes. Under controlled conditions of photoperiod, temperature, and water quality, hardhead catfish display nonrandom oscillations in angular orientation of locomotive activity. There appears to be annual, bimodal cycles for all three of these variables. The cycles match with the seasonal inshore-offshore migrations of hardhead catfish. Photoperiod appears to be the exogenous cue that triggers the cyclic changes in behavior. The presence of this seasonal behavior indicates that a circadian neural mechanism may exist in hardhead catfish.[10]

Communication

Chemical

Hardhead catfish respond to chemicals released by injured individuals with increased activity, illustrating communication among catfish. Their activity level was highest right after the onset of the chemical stimulus. They also respond to chemical cues from injured sailfin mollies, but this response was weaker than that of the response from their own species. After examining the epidermis of the hardhead catfish, the alarm substance cells apparently were similar to those of freshwater catfish. These chemical responses had only been seen in freshwater ostariophysans. Hardhead catfish are the first marine ostariophysans found to elicit this type of alarm reaction.[11]

Echolocation

Furthermore, hardhead catfish are the first indicator that Osteichthyes possibly could use directional hearing to detect obstacles. Emissions of low-frequency sounds were related to the detection and avoidance of close obstacles. Individuals within the group that produced sound avoided obstacles, whereas silent individuals crashed into obstacles frequently. Many fish have been associated with sound production for alarm, territorial, and courtship purposes, but sound probing of surroundings seems to be only be seen in hardhead catfish. So far, no evidence exists for far-field echolocation, such as seen in bats or toothed whales. The signal parameters have low frequency and amplitude, so far-field reverberations are unlikely to be useful. If echolocation exists, it is likely only useful in the near field by the catfish.[12]

Sound production

Some evidence indicates sound production in hardhead catfish is differentiated both mechanistically and contextually. Mechanistically, sound can be produced in different ways. Thin bones by the swim bladder can be vibrated by specialized sonic muscles. Also, grinding of the pharyngeal teeth and rubbing of the pectoral spines against the pectoral girdle can produce sound. These two mechanisms appear to be evolved fright responses by the hardhead catfish. Some argue that hardhead catfish use an unrefined form of sonar as a means of echolocation, which also implies some directional hearing ability. It is possible, but insofar unproven, that sound is used in courtship and spawning.[13]

Lifecycle and reproduction

The hardhead catfish has a reproductive season from around May to September.[14] Males and females reach sexual maturity before age 2.[8][14] Females at maturity are around 12.6–26.5 cm (5.0–10.4 in), and males typically are slightly larger, around 25 cm (9.8 in). At maturity, females develop flap-like fatty tissue by their pelvic fins, which results in them having larger pelvic fins than males. These enhanced pelvic fins may be the site of fertilization and play a part in moving the fertilized eggs to the male mouthbrooder for incubation. Another possibility is that males pick up eggs from depressions in the sand, as eggs tend to be demersal.[8] They also die after 4 years.

Parental care

Mouthbrooding

Like other members of the Ariidae, hardhead catfish are paternal mouthbrooders. After spawning, the male carries the eggs in his mouth until they hatch. Several nonfunctioning eggs within the brood attach to the larger, viable eggs. These nonfunctioning eggs may be used as food for the male mouthbrooder, since mouthbrooders do not feed while they are taking care of the brood.[8] Oral incubations continue through the yolk-sac larval state, for a total length around 8–11 weeks.[15] Under laboratory conditions, offspring can hatch in roughly 30 days.[8] The offspring are roughly 6–8 cm long and slowly adapt to adult behavior, such as opportunistic bottom-feeding and scavenging.[15] At absorption of the yolk sac, juveniles begin to show adult characteristics.[8] The parental male can choose to carry the young after they have hatched until they are larger and capable of surviving on their own.[16]

Advantages

Many advantages to mouthbrooding exist as opposed to other forms of parental care, such as bubble nesting. Mouthbrooders are able to freely move with the eggs in their mouths, thus can move as necessary to protect both themselves and the broods. Though mouthbrooding requires more energy by the male, the chance of his young surviving to adulthood is greater, thus reproducing and continuing his genes; the eggs are not defenseless while in their father's mouth.[17] Mouthbrooding by males counters the relatively low fecundity of females, which only have 20-65 eggs per spawning episode.[8] Finally, through breathing, the male is able to keep the brood well oxygenated, which also increases brood survival.[17]

Fishing

Hardhead catfish are voracious feeders and will bite on almost any natural bait. Hardhead catfish are also known to steal bait. Shrimp is a particularly effective bait to use. When fishing for this species in fresh water, assorted meats tend to work best as bait. For example: bacon, chicken, cuts of steak, and smaller fish. Hardhead catfish are generally regarded as an undesirable catch by most anglers, largely due to the risk associated with handling the venomous fish, as well as its 'fishy' taste as opposed to desirable game fish. Hardhead catfish are edible, but like all catfish, require some effort to clean. It is one of the 30 most recreationally harvested species in the five-county area (Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin) encompassing the Indian River Lagoon in central Florida.[8] From 1997-2001, 361,022 hardhead catfish were harvested within 200 miles of the shore in the IRL region.

Hardheads are also harvested for industrial purposes in commercial bottom-trawling operations. Annual harvests vary greatly, but from 1987–2001, 1.04 million pounds of marine catfishes (including both the hardhead catfish and the gafftopsail catfish) were harvested in the IRL region. The harvest was valued at $777,497.[8]

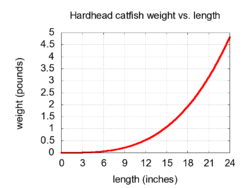

Weight and length

Hardhead catfish weigh around 1 lb (0.45 kg) and measure 10 to 12 in (25–30 cm) long.

As hardhead catfish grow longer, they increase in weight. The relationship between length and weight is not linear. The relationship between total length (L, in inches) and total weight (W, in pounds) for nearly all species of fish can be expressed by an equation of the form:

Invariably, b is close to 3.0 for all species, and c is a constant that varies among species. The relationship described in this section suggests that a 20 in (51 cm) hardhead catfish will weigh about 3 lb (1.4 kg), while a 25 in (64 cm) hardhead catfish will likely weigh at least 6 lb (2.7 kg).

References

- Betancur, R. (2015). "Ariopsis felis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T190456A1952682. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T190456A1952682.en.

- "Ariopsis felis (Linnaeus, 1766)". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). Species of Ariopsis in FishBase. February 2017 version.

- Webster, Pearse. Hardhead Catfish. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. http://www.dnr.sc.gov/cwcs/pdf/Hardheadcatfish.pdf

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Ariopsis felis" in FishBase. February 2017 version.

- "Hardhead Catfish_ Arius felis".

- "Hardhead Catfish_ Arius felis".

- Hill, K. "Ariopsis felis". Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Yáñez-Arancibia, Alejandro; Ana Laura Lara-Domínguez (30 November 1988). "Ecology of three sea catfishes (Ariidae) in a tropical coastal ecosystem-Southern Gulf of Mexico". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 49: 215–230. Bibcode:1988MEPS...49..215Y. doi:10.3354/meps049215.

- Steele, Craig W. (June 1985). "Non-Random, Seasonal Oscillations in the Orientation and Locomotor Activity of Sea Catfish (Arius felis) in a Multiple-Choice Situation". Biological Bulletin. 168 (3): 359–376. doi:10.2307/1541518. JSTOR 1541518.

- Smith, Michael E. (1 January 2000). Journal of Chemical Ecology. 26 (7): 1635–1647. doi:10.1023/A:1005586812771. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Schmidtke, Daniel; Jochen Schulz; Jörg Hartung; Karl-Heinz Esser (31 May 2013). "Structure and Possible Functions of Constant-Frequency Calls in Ariopsis seemanni (Osteichthyes, Ariidae)". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e64864. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864864S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064864. PMC 3669340. PMID 23741408.

- "Hardhead Sea Catfish". Discovery of Sound in the Sea. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Surge, Donna; Karen Jo Walker (22 November 2005). "Oxygen isotope composition of modern archaeological otoliths from the estuarine hardhead catfish (Ariopsis felis) and their potential to record low-latitude climate change". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 228 (1–2): 179–191. Bibcode:2005PPP...228..179S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.03.051.

- Avise, John C.; Carol A. Reeb; Nancy C. Saunders (September 1987). "Geographic Population Structure and Species Differences in Mitochondrial DNA of Mouthbrooding Marine Catfishes (Ariidae) and Demersal Spawning Toadfishes (Batrachoididae)". Evolution. 41 (5): 991–1002. doi:10.2307/2409187. JSTOR 2409187.

- Jones, P.W., F.D Martin, J.D. Hardy Jr. (1978). Development of fishes of the mid-Atlantic Bight: an atlas of egg, larval, and juvenile stages. Volume I: Acipenseridae through Ictaluridae. Ft. Collins, CO: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Programs.

- Hellweg, Mike. "I've Got a New Mouthbrooding Betta-Now What?". Species Maintenance Program. Retrieved 2 October 2013.