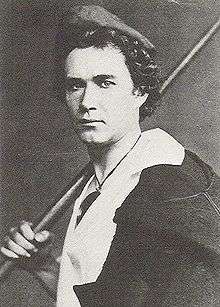

Harald Scharff

Harald Scharff (20 February 1836 – 3 January 1912) was a danseur associated with the Royal Danish Theatre in the mid-19th century who succeeded August Bournonville as the Danish ballet's principal male dancer upon the latter's retirement from the stage. Scharff's physical handsomeness and his flamboyant dance style brought him great acclaim, and his performances in Bournonville's Flower Festival in Genzano and Napoli were triumphs.

Scharff was an intimate friend (possibly a lover in the early 1860s) of the poet Hans Christian Andersen. Andersen's "The Snowman" is believed to have been inspired by their relationship. Scharff first met Andersen when the latter was in his fifties. The two were, at the very least, close friends for a time and Andersen was clearly infatuated. It is hard to tell if their relationship was truly sexual, though Andersen's journals imply that it was so.[1] Scharff had various dinners alone with Andersen and his gift of a silver toothbrush to the poet on his fifty-seventh birthday marked their relationship as incredibly close.[2]

Their relationship eventually cooled and Scharff became engaged to Camilla Petersen, a fellow dancer, but married Elvida Møller in 1874. Scharff's career came to a sudden halt in 1871 when he chipped a kneecap during rehearsal. He turned to acting without extraordinary success and died in 1912.

Scharff and Andersen

In 1857, the 21-year-old Scharff was on holiday in Paris with his 28-year-old Copenhagen housemate, the actor Lauritz Eckardt when he first met fellow Dane Hans Christian Andersen. The poet was returning to Copenhagen via Paris following a visit to Charles Dickens in England. Scharff and Andersen toured Notre-Dame de Paris together.[3][4] Scharff was a highly regarded artist in Denmark, having succeeded August Bournonville as principal male dancer at the Royal Ballet. Following his retirement, Bournonville described Scharff as “full of life and imagination... he is undoubtedly the finest lover we have had since I left!"[5] Scharff and his housemate were members of a circle of young, unmarried men associated with the Royal Theatre—a circle which Jonas Collin, the grandson of Andersen's first benefactor in Copenhagen despised, expressing his loathing and disgust in letters to Andersen in the early 1860s.[3]

In early July 1860, Scharff and Eckardt met Andersen by accident in Bavaria. The three kept constant company for a week, and it is probable that Andersen fell in love with Scharff at this time.[4] Scharff and Eckardt departed for Salzburg, and Andersen, according to his diary, did not "feel at all well" when the two young men departed.[6][note 1][7] A liaison with a celebrated and distinguished man such as Andersen must have held some attraction for the young Scharff, and a correspondence between the two began.[note 2] Andersen sent Scharff his photograph.[8]

Following the departure of Scharff and Eckardt for Salzburg, Andersen traveled to Switzerland but grew despondent and returned to Copenhagen. He spent the Christmas holidays at the estate of an aristocratic friend. His spirits lifted with the festivities and "The Snowman” was composed on New Year’s Eve 1860–61.[9] Andersen determined to fully open his heart to Scharff. He sent the young dancer a photograph of himself in a languid and seductive pose with a salutation using the intimate “Du” form: "Dear Scharf, here you have again Hans Christian Andersen." The two men exchanged birthday gifts in the early months of 1861: Andersen gave Scharff a five-volume collection of his tales, and Scharff gave Andersen a reproduction of Danish sculptor Herman Bissen's Minerva. Copenhagen left Andersen restlessness and ill-tempered, however, and he left for Rome on 4 April 1861.[10]

When Andersen returned to Copenhagen at the start of the new year 1862, Scharff was waiting for him.[11] In his diary entry for 2 January 1862, Andersen noted that Scharff "bounded up to me; threw himself round my neck and kissed me!" In other entries for January 1862, he described Scharff as "deeply devoted… very intimate… ardent and loving". In February, the poet observed that Scharff was "intimate and communicative" and in March he noted "a visit from Scharff... exchanged with him all the little secrets of the heart; I long for him daily." Later in March he wrote, "Scharff very loving... I gave him my picture." Scharff gave a silver toothbrush engraved with his name and the date to Andersen on his 57th birthday. In the winter of 1861–62, the two men entered a full-blown love affair that brought Andersen "joy, some kind of sexual fulfillment and a temporary end to loneliness."[12] He was not discreet in his conduct with Scharff, and displayed his feelings much too openly. Onlookers regarded the relationship as improper and ridiculous. In his diary for March 1862, Andersen referred to this time in his life as his "erotic period".[13]

The affair eventually came to an end. Scharff withdrew gradually from the relationship as he focused on his friendship with the now married Eckardt. On 27 August 1863, Andersen noted in his diary that Scharff’s passion had cooled and the dancer (whom he at one time described as a "butterfly who flits around sympathetically") was flirting with others.[14][15]

On 13 November 1863, Andersen wrote, "Scharff has not visited me in eight days; with him it is over." In December, he read fairy tales at Eckhardt's house where Scharff and a dancer named Camilla Petersen were present; the two would become engaged though they would never marry. Like the other young men with whom Andersen was involved at various points in his lifetime, Scharff would move from homosexual to heterosexual relationships. The passionate relationship was over between the two men although Andersen would try unsuccessfully several times to lure Scharff into another relationship without success. When they were forced to stay overnight in a hotel in Helsingør the summer of 1864 while touring, for example, Andersen reserved a double room for the two of them, but Scharff insisted on having his own room.[14][note 3][16]

References

Notes

- The day after their departure, Andersen (who usually thought of himself as ugly) had his photograph taken by Franz Hanfstaengl and wrote: “I’ve never seen such a lovely yet life-like portrait of myself. I was completely surprised, astonished, that the sunlight could make such a beautiful figure of my face.”

- All letters between Andersen and Scharff have been destroyed.

- In 1864, after a break of 12 years with drama, Andersen composed three new plays for the Copenhagen theatres that examined brotherly love and deep feelings between men. One reason for the poet's re-entry into a field in which he had experienced past failures was quite possibly the opportunity it presented him to hover about Scharff at the Royal Theatre. He revised his 1832 opera The Raven and, when it played in Copenhagen on 23 April 1865, Scharff portrayed a vampire who sucked the blood of a young man on his wedding night. In 1871, Bournonville composed a ballet based on Andersen's "The Steadfast Tin Soldier" with the work's principal role intended for Scharff, but the dancer chipped a kneecap during a rehearsal of The Troubadour in November 1871 and, as a result, was forced to bring his career as a dancer to an end. He turned to acting without extraordinary success, married the ballerina Elvida Møller in 1874 (who eventually disappeared from his life), and spent his last years in the St. Hans insane asylum, where he died in 1912.

Footnotes

- "Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller". Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 2001-11-01. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- "Andersen's Fairy Tales". The Advocate. 2005-04-26. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- AndersenJ 2005, p. 474

- Wullschlager 2000, p. 373

- Terry 1979, pp. 71,97–98

- Wullschlager 2000, p. 374

- Wullschlager 2000, pp. 374–376

- Wullschlager 2000, p. 377

- Wullschlager 2000, pp. 377–378

- Wullschlager 2000, p. 379

- AndersenJ 2005, p. 475

- Wullschlager 2000, pp. 387–389

- AndersenJ 2005, pp. 475–476

- AndersenJ 2005, p. 477

- Wullschlager 2000, pp. 373,391

- AndersenJ 2005, pp. 477–479

Bibliography

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2005) [2004], Jackie Wullschlager (ed.), Fairy Tales, Tiina Nunnally, New York: Viking, ISBN 0-670-03377-4

- Andersen, Jens (2005) [2003], Hans Christian Andersen: A New Life, Tiina Nunnally, New York, Woodstock, and London: Overlook Duckworth, ISBN 1-58567-737-X

- Terry, Walter (1979), The King's Ballet Master, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, ISBN 0-396-07722-6

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2002) [2000], Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-91747-9

- Zipes, Jack (2005), Hans Christian Andersen: The Misunderstood Storyteller, New York and London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-97433-X