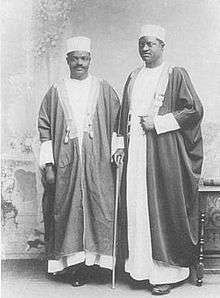

Ham Mukasa

Ham Mukasa (c. 1870–1956)[1][2] was a vizier in the court of Mutesa I of Buganda (in present-day Uganda) and later secretary to Apolo Kagwa. He was fluent in both English and Swahili. He wrote one of the first glossaries of the Ganda language.[3]

Early life

Mukasa was the son of Makabugo Sensalire, a minor chief in Buddu (in present-day Masaka District).[4] He converted to Christianity at a young age.[3] He suffered serious injury in the 1886 massacre of Christians by Mwanga II.[5] As a result, he had a weak leg.[6] Around 1898, he married Наnnаh Mаwеmukо, the daughter of a former chief minister (Katikkiro) of Buganda.[4]

Career

Ham Mukasa was placed in the palace of Kabaka Mutesa I as a page at the age of nine by his father, a clan chief in Buganda.[7] While in the palace, Mukasa at first received instruction from Islamic teachers who held sway in Mutesa's court; however, he was later drawn to the Protestants, who baptised him Ham.[7] It was as a christian, and as a Protestant, that he took part in Buganda's religious wars of 1888-1892.[7]

Mukasa was appointed the ssaza (county) chief of Kyaggwe - known as the Ssekiboobo - in 1905,[8] and served in the position until 1935 when he retired.[9]

Journeys in England

Mukasa's book Uganda's Katikiro in England details his experiences on his journey from his homeland to the coronation of Edward VII of the United Kingdom, as secretary to Katikkiro (Prime Minister) Apolo Kagwa.[10] It was translated into English by Ernest Millar of the Church Mission Society in Uganda.[6] In London, Mukasa stayed at Alexandra Palace, and visited the London Hippodrome, attended a play in Drury Lane, and met with a variety of people such as writer Henry Morton Stanley and ex-governor of Uganda Harry Johnston.[11]

Ham Mukasa returned to England in 1913,[8] this time accompanying the child Kabaka Cwa who was on an official visit.[12]

Personal life

Ham Mukasa married his first wife, Hanna Wawemuko when he was 27 years old.[13] They had four children together. Wawemuko died in 1919, and Mukasa remarried a year later. He had ten children with his second wife, Sarah Nabikolo.[13]

Victoria Sarah Kisosonkole, Mukasa's daughter with Hanna Wawemuko, was the mother of Damali Kisosonkole and Sarah Kisosonkole, who were both married to Ssekabaka Edward Muteesa II.[14] Sarah Kisosonkole is the mother of the current Kabaka of Buganda, Muwenda Mutebi II.[15]

References

- Notes

- Barringer, Terry (1996). "The Drum, the Church, and the Camera: Ham Mukasa and C. W. Hattersley in Uganda". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 20 (2): 66–70. doi:10.1177/239693939602000204.

- "History in progress Uganda, Part 1: the Ham Mukasa archive (EAP656)". British Library. 2017-09-06.

- Gikandi 2003

- Pirouet 2004

- Gikandi 1998, p. 16

- Green 1998, p. 19

- Rowe, John A. (1989). "Eyewitness Accounts of Buganda History: The Memoirs of Ham Mukasa and His Generation". Ethnohistory. 36 (1): 61–71. doi:10.2307/482741. JSTOR 482741.

- Ham., Mukasa (1998). Uganda's Katikiro in England. Gikandi, Simon. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719054370. OCLC 38948304.

- "Ham Mukasa Ssekibobo Of Buganda".

- Mukasa, Ham (1904). Uganda's Katikiro in England: Being the Official Account of His Visit to the Coronation of His Majesty Edward VII. London: Hutchinson & Company.

- Green 1998, p. 21

- P., Green, Jeffrey (1998). Black Edwardians : Black people in Britain, 1901-1914. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 1136318232. OCLC 819635740.

- "The Uganda journal". ufdc.ufl.edu. p. 185. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- "Lady Damali Kisosonkole". Bukedde Online. 2010-07-14. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "First Ladies who shunned the Limelight". New Vision. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Bibliography

- Gikandi, Simon (1998), "African subjects and the colonial project", in Gikandi, Simon; Mukasa, Ham (eds.), Uganda's Katikiro in England, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-5437-2

- Green, Jeffrey P. (1998), Black Edwardians: Black people in Britain, 1901-1914 (illustrated/annotated ed.), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-7146-4426-4

- Gikandi, Simon (2003), "Mukasa, Ham", Encyclopedia of African Literature, Taylor & Francis, pp. 347–348, ISBN 978-0-415-23019-3

- Pirouet, M. Louise; Harrison, B. (2004), "Mukasa, Ham (c.1871–1956)", Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75913