Hallington Reservoirs

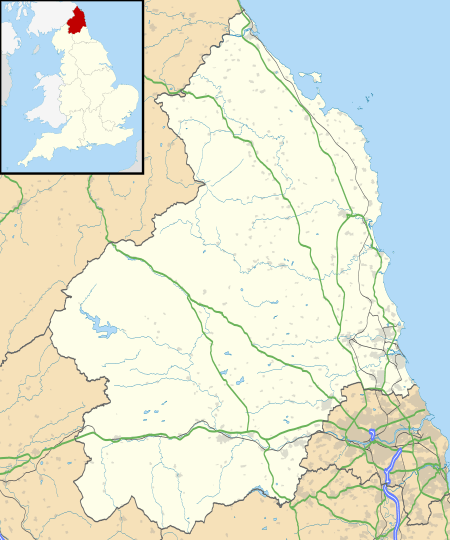

Hallington Reservoirs are located near the small village of Colwell, Northumberland, England on the B6342 road off the A68 road, and 7 miles (11 km) north of Corbridge. Hallington is actually two small reservoirs: Hallington Reservoir West and Hallington Reservoir East, which are separated by a dam.[2]

| Hallington Reservoirs | |

|---|---|

Hallington East Reservoir near Cheviot Farm | |

| Location | Northumberland, England grid reference NY969763 |

| Coordinates | 55.081°N 2.050°W |

| Type | Reservoir |

| Surface area | 257 acres (104 ha)[1] |

| Surface elevation | 495 feet (151 m)[1] |

Water was first collected from the area by an aqueduct intercepting streams, which was built between 1857 and 1859 by the Whittle Dean Water Company. The work included a 3,887-yard (3,554 m) tunnel to allow the water to flow by gravity from the collecting area through a ridge of higher ground to the company's main reservoirs at Whittle Dene. An Act of Parliament was obtained in 1863 to build Hallington Reservoir, which also changed the company name to the Newcastle and Gaateshead Water Company. After some delays work started on construction in 1869, and the reservoir was completed in 1872. Water was fed from it to Whittle Dene through the existing aqueduct and tunnel.

As the populations of Newcastle and Gateshead continued to grow, more water was needed, and a second reservoir was constructed at Hallington, known as the West Reservoir. Land was purchased in 1880, and work started in 1884, using direct labour under the supervision of John Forster, the resident engineer. Despite appalling weather in the winters of 1886 and 1887, and a poor understanding of soil mechanics which affected the construction of the dams, the reservoir was completed in 1889, with filling beginning in May 1889. Hallington received water from other reservoirs constructed further to the north-west, notably at Swinburn, Colt Crag and Catcleugh. The existing aqueduct and tunnel to Whittle Dene was found to be inadequate for the volume of water needed, and a second tunnel, parallel to the first, was constructed between 1898 and 1905. Narrow gauge railways were built to aid the construction of the first reservoir and the second tunnel.

The reservoirs are a designated Local Wildlife Site. The east reservoir is partially surrounded by mixed woodland, and small-fruited yellow sedge, a very rare marginal plant, grows near the dam between the two reservoirs. Several species of waders populated the reservoirs in the autumn, and it provides over-wintering habitat for numerous wildfowl.

History

The reservoir was built at the end of the 19th century for the Newcastle and Gateshead Water Company. The reservoir forms part of a series of reservoirs along the A68 which are connected by tunnels and aqueducts from Catcleugh Reservoir to Whittle Dene;[2] from where drinking water is supplied to Newcastle upon Tyne, Gateshead, and some surrounding areas. The reservoirs that form the chain are, from northwest to southeast: Catcleugh Reservoir → Colt Crag Reservoir → Little Swinburne Reservoir → Hallington Reservoirs → Whittle Dene.

Newcastle and Gateshead had been provided with water from reservoirs at Whittle Dene, but the rapid growth of the towns in the mid-nineteenth century, coupled with several years of drought, meant that these were inadequate. The Whittle Dean Water Company, as it was then known, had attempted to get powers to build a reservoir on the Swin Burn, but their Act of Parliament obtained in 1854 had been amended after Thomas Riddell objected to the reservoir.[3] Although the reservoir had been removed from the Act, they were empowered to build an aqueduct, which would intercept a number of streams between Hallington and Ryal, to the north west of Matfen. In order to convey the water to the main reservoirs at Whittle Dean, a tunnel was required through a ridge of higher land.[4] Tenders for the construction of the tunnel were sought in 1856, and from the 25 received, the contract was awarded to R Mains & Co, who had quoted £7,101 for the work. An arrangement with the Duke of Northumberland was negotiated, to allow a brickworks to be built on his land, as a way of reducing transport costs for materials.[5]

Work on the construction began in 1857, but by February 1858 Mains had failed to get very far. He was paid £500 for the work he had done, and a second contract was awarded to Roper & Smith. By March, the new contractor was working on seven of the twelve shafts and some tunnelling had been started, although the works were hampered by the ingress of water. The directors were hoping for quick completion of the tunnel, to prevent difficulties with supplying water to the towns. They offered Roper & Smith an additional £300, if they would set men on to tunnelling from all of the available shafts. Roper & Smith were facing financial difficulties by November 1858, and the tunnel was not expected to be completed for another two years. The directors offered another £1,000 if the work could be completed in a year, but the contractor did not feel able to commit to such a deadline. As a consequence, Richard Cail took over the works on 1 December 1858.[6]

At that time, 1,471 yards (1,345 m) of the tunnel had been excavated, out of a total of 3,887 yards (3,554 m). From sums of money paid to Cail, it would appear that he was employing 200 to 300 men on the contract, and the tunnelling progressed well, although there were difficulties at both ends, where the limestone was particularly hard. The tunnel was completed by 31 December 1859, thirteen months after Cail took over the contract.[7] Shortly afterwards, much of the plant used on the project was put up for sale, including nine steam engines, 60 tons of bridge rails, 14 sets of pumps and two brick and tile making machines. The land at Tongues Farm, where the brickworks had been operating, was returned to agricultural use. Many of the workmen had lived in huts in this remote area, and those were demolished. Most of the shafts were arched over and filled in. The main fault identified was a step at the western end, resulting in water standing to a depth of 18 inches (46 cm), which Cail claimed was due to inaccurate drawings.[8]

In 1862 the company found out that Riddell would not object to a reservoir at Hallington, and so this was included in an Act of Parliament obtained in 1863. The engineer for the company was John Frederick Bateman, but it was Thomas Hawksley who steered the bill through Parliament, so he may have been acting to protect the interests of Newcastle Corporation.[3]

The landowners were Henry H Riddell and Catharine Ann Tevelyan, and following negotiations with both parties, the company paid £9,500 for the land on which to construct the reservoir. The contract ensured that the fishing and shooting rights were retained by the landowners, but were also available to the directors and their friends. Measurement of the flow in various streams in the vicinity had shown that the yield might not be as high as Bateman had estimated.[9] The Act authorising the reservoir received Royal Assent on 11 May 1863, and also changed the name of the company to the Newcastle and Gateshead Water Company, reflecting the area they supplied rather than where the water came from. In addition to the reservoir, two aqueducts were authorised, one to the east and another to the west, which fed water into the reservoir.[10]

The enabling Act had imposed time restrictions on completing the reservoir, and in 1866 the company went back to Parliament for a second Act, which extended the time limits.[11] The contract for construction was given to McGuire, at a cost of £19,900 and work began on the project on 11 September 1869. The directors decided that no payment would be made until the contractor had spent £2,000. Three months later, McGuire was in financial trouble, and the company decided to complete the work themselves. McGuire was hired to oversee the work, and paid a salary of £200 per year.[12] Construction of the reservoir was aided by a narrow gauge railway, some 3 miles (4.8 km) in length, built to bring stone from Moot Law Quarry.[13] A locomotive to work the line was obtained from Black, Hawthorn & Co. of Gateshead. The workers were affected by an outbreak of smallpox, and there were some problems with settlement of the western embankment. Because the company were desperately short of water, they started impounding water in the reservoir in December 1870, when the work done thus far meant that it could safely hold 250 million imperial gallons (1,100 Ml), nearly half of its capacity when it was completed in 1872. Surplus plant was sold off in October 1871, the locomotive was sold in spring 1872, and another sale took place in November 1972. When the work was finished, McGuire was paid his £2,000,.[14] Water from the reservoir was conveyed to Whittle Dean using the aqueduct and tunnel which had been completed in 1859.[13]

It is unclear how well the new reservoir performed. It had a capacity of 600 million imperial gallons (2,700 Ml), effectively doubling the amount of water the company could store. Bateman had estimated that the rainfall in the area would be 26 inches (660 mm) per year, whereas records for a ten-year period showed that it was actually 28.8 inches (730 mm). Despite these facts, the company expressed disappointment at the yield it gave, and the Newcastle Daily Journal, in an article sympathetic to the plight of the company published in September 1874, stated that there had been a miscalculation in the yield available.[15] John Furness Tone wrote a letter to Newcastle Council stating that the capacity of the reservoir was reduced due to the fissured nature of the underlying rock in the area. He stated that Bateman had built the reservoir against his advice, which surprised the company's engineer, as Tone and Robert Nicholson had recommended the Hallington reservoir while working for the Whittle Dean Water Company.[16]

West reservoir

With the company struggling to meet the volume of water needed by the rapidly expanding towns of Newcastle and Gateshead, it decided to build a second reservoir at Hallington and two at Swinburn.[17] By the time a bill was placed before Parliament in February 1876, there were three reservoirs at Swinburn. The bill was opposed by both Newcastle and Gateshead Corporations, although their objections were eventually withdrawn, and by John Gifford Riddell, on whose land the Swinburn reservoirs would be built. Lower Swinburn reservoir was deleted in the committee stage of the bill, which became an Act of Parliament in July 1976.[18] The company obtained a second Act in 1877, to authorise alterations to the Swinburn scheme, and at the same time extended the time allowed to build West Hallington reservoir.[19] Land was bought in 1880, but construction did not start until Colt Crag reservoir, the revised Upper Swinburn reservoir, was completed. John Forster, the resident engineer, was paid an additional £100 per year to supervise and direct the works, which began in 1884.[20]

A source of stone was located near to Colt Crag reservoir, and a 2-mile (3.2 km) narrow gauge railway was built to transport it to the site. Clay was obtained from the site for the embankments, and bricks were made from book-leaf marl. This covered the area, and would subsequently be the cause of problems with the embankments. The company employed direct labour to build the reservoir, and some 60 navvies were engaged in this task. They used waggons and a hauling engine to move the material. Forster found that using manual labour was more cost-effective than using steam navvies. Work on the reservoir was suspended in early 1886 and early 1887, due to appalling weather conditions, and there were regular slippages in the embankments.[21] The slope of the embankments was reduced, from 1 in 2 to 1 in 2.5, but a knowledge of soil mechanics was clearly lacking. Water was also a problem, and a spring which produced 250,000 imperial gallons (1.1 Ml) per day was discovered under one of the embankments in 1877. The reservoir started to fill in May 1889, although various tasks were still to be completed. In six years, some 516,000 cubic yards (395,000 m3) of earth had been moved, 33,000 waggons of stone had been transported along the railway, and 670,000 bricks had been manufactured and laid. The work had cost considerably more than the £40,000 that Forster had estimated. Labour along had cost £51,631, of which £23,557 was for extras, but Forster was not alone in miscalculating costs, as the company had experienced similar problems with projects supervised by an engineer as eminent at Bateman.[22]

By 1898, reservoirs at Swinburn and Colt Crag had been completed, and a new reservoir at Catcleugh was in progress. The water was conveyed to Hallington by pipelines and aqueducts, and when flows from there to Whittle Dean exceeded 9 million imperial gallons (41 Ml) per day, the aqueducts overflowed with a corresponding loss of water. The company looked at building a new pipeline with a capacity of 15 million imperial gallons (68 Ml) per day, but when they presented a bill to Parliament they had decided on a new tunnel, running parallel to the existing tunnel near Ryal, into which water would be fed by a pipeline from the Hallington reservoir. The Act also allowed them to build a narrow gauge railway from Matfen, at the eastern end of the tunnel, to Wylam, on the River Tyne, via Whittle Dene. An extension from there, across the river to connect to the North Eastern Railway was also authorised, and the bill passed through Parliament unopposed, becoming an Act of Parliament in August 1898.[23]

A working site was established at the eastern end of the tunnel, with huts, offices, a canteen, spoil heaps and sidings for the railway. The work was managed by a Resident Engineer called Chamberlain, who presented reports to meetings of the directors.[24] Two shafts were built, allowing work to continue on six faces, but the works were lit by electricity, and the company spent £1,000 on drilling equipment from Schram & Co, which was powered by compressed air. A third shaft was later opened near the eastern end, providing eight faces for tunnelling. The tunnel was some 3 miles (4.8 km) long, and with so few shafts, boreholes were drilled down from the surface into the headings to check on its alignment. By 1903, one-third of the tunnel had been completed, and it was finished in 1905. One unfortunate consequence of the work was that the tunnel cut through the source of the spring that supplied Matfen village with water, and the company had to provide a new source. Once the works were completed, the railway between Matfen and Whittle Dene was lifted.[25] The church at Ryal contains a memorial to those who died during the construction of the tunnel.[26]

The aqueduct from West Hallington reservoir consistently suffered from leakage, and this was eventually solved by lining it with concrete, some time prior to 1911. In that year there was another problem when a water main burst at the reservoir. Soon afterwards, there was a partial collapse of the upstream end of the old tunnel, which conveyed water to Whittle Dean. A new shaft was constructed to gain access to the fault. Timber was then used to shore up the affected section, after which it was relined.[27] In 1942 the company board looked at the possibility of constructing a third reservoir at Hallington, and some trial borings were made, but a report in June 1943 suggested that such a reservoir would only yield 3.3 million imperial gallons (15 Ml) per day, and that a new reservoir at Kielder would be a better proposition.[28] The company had obtained an Act of Parliament in 1938 for various works, including a pipeline from Barrasford to West Hallington, to enable water to be pumped from the North Tyne, and repairs to the Ryal tunnel and aqueduct.[29] The Barrasford pipeline and pumping station were completed by autumn 1940.[30] The Act had stipulated that all works should be completed by 1945, and with the end of the Second World War in sight, repairs to the tunnel and aqueduct were completed before the deadline passed.[31]

Responsibility for the reservoirs passed to the Northumbrian Water Authority in April 1974, as a result of the passing of the Water Act 1973.[32] It then passed to Northumbrian Water when the water industry was privatised in 1989.[33]

Flora and fauna

The north-western part of Hallington Reservoir East is surrounded by mixed woodland, including evergreen varieties such as Scots pine and larch, with some native deciduous species, such as beech, willow, and sycamore. The dam between the two reservoirs provides habitat for marginal plants, particularly the very rare small-fruited yellow sedge.[2]

The reservoirs are used for overwintering by several varieties of wildfowl, including wigeon, teal, and mallard, while during the autumn waders including dunlin, black-headed, and common gulls can be seen in large numbers. The surrounding area still had a population of red squirrels which are seen from time to time, as are otters, badgers, and bats. The aqueduct that feeds into the reservoirs had been colonised by a healthy population of white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes, when a survey was carried out in 2009.[2]

Fishing

Hallington is fished by many anglers.

Bibliography

- Porter, Elizabeth (1978). Water Management in England and Wales. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21865-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rennison, Robert William (1979). Water to Tyneside. Newcastle and Gateshead Water Company. ISBN 978-0-9506547-0-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- SRM (2008). "Structure of the UK Water Industry". Water Research Centre. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- "Hallington Reservoirs". British Lakes. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "NWA Reservoirs". 2006–2009. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Rennison 1979, p. 98.

- Rennison 1979, p. 79.

- Rennison 1979, p. 80.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 80-81.

- Rennison 1979, p. 81.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 81-82.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 98-99.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 100-101.

- Rennison 1979, p. 106.

- Rennison 1979, p. 119.

- Rennison 1979, p. 101.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 119-120.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 125-127.

- Rennison 1979, p. 130.

- Rennison 1979, p. 141.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 143-144.

- Rennison 1979, p. 146.

- Rennison 1979, p. 159.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 143, 159.

- Rennison 1979, p. 160.

- Rennison 1979, p. 220.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 221-222.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 222-223.

- "Northern Vicar's Blog". 24 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019.

- Rennison 1979, p. 229.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 250-251.

- Rennison 1979, pp. 245-246.

- Rennison 1979, p. 247.

- Rennison 1979, p. 251.

- Porter 1978, pp. 21,27.

- SRM 2008, p. 1.