Hemocytometer

The hemocytometer (or haemocytometer) is a counting-chamber device originally designed and usually used for counting blood cells.[1]

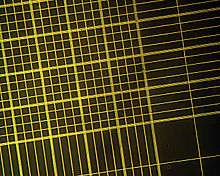

The hemocytometer was invented by Louis-Charles Malassez and consists of a thick glass microscope slide with a rectangular indentation that creates a chamber. This chamber is engraved with a laser-etched grid of perpendicular lines. The device is carefully crafted so that the area bounded by the lines is known, and the depth of the chamber is also known. By observing a defined area of the grid, it is therefore possible to count the number of cells or particles in a specific volume of fluid, and thereby calculate the concentration of cells in the fluid overall. A well used type of hemocytometer is the Neubauer counting chamber.[2]

Principles

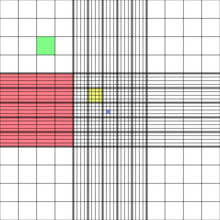

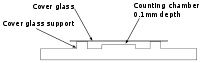

The gridded area of the hemocytometer consists of nine 1 x 1 mm (1 mm2) squares. These are subdivided in three directions; 0.25 x 0.25 mm (0.0625 mm2), 0.25 x 0.20 mm (0.05 mm2) and 0.20 x 0.20 mm (0.04 mm2). The central square is further subdivided into 0.05 x 0.05 mm (0.0025 mm2) squares. The raised edges of the hemocytometer hold the coverslip 0.1 mm off the marked grid, giving each square a defined volume (see figure on the right).[3]

| Dimensions | Area | Volume at 0.1 mm depth |

|---|---|---|

| 1 x 1 mm | 1 mm2 | 100 nL |

| 0.25 x 0.25 mm | 0.0625 mm2 | 6.25 nL |

| 0.25 x 0.20 mm | 0.05 mm2 | 5 nL |

| 0.20 x 0.20 mm | 0.04 mm2 | 4 nL |

| 0.05 x 0.05 mm | 0.0025 mm2 | 0.25 nL |

Usage

To use the hemocytometer, first make sure that the special coverslip provided with the counting chamber is properly positioned on the surface of the counting chamber. When the two glass surfaces are in proper contact Newton's rings can be observed. If so, the cell suspension is applied to the edge of the coverslip to be sucked into the void by capillary action which completely fills the chamber with the sample. The number of cells in the chamber can be determined by direct counting using a microscope, and visually distinguishable cells can be differentially counted. The number of cells in the chamber is used to calculate the concentration or density of the cells in the mixture the sample comes from. It is the number of cells in the chamber divided by the chamber's volume, which is known from the start, taking account of any dilutions and counting shortcuts:

where the volume of the diluted sample (after dilution) divided by the volume of the original mixture in the sample (before dilution) is the dilution factor. For example, if the volume of the original mixture was 20μL and it was diluted once (by adding 20μL dilutant), then the second term in parentheses is 40μL/20μL. The volume of the squares counted is the one shown in the table at the top, depending on the size (see figure on the right). The number of cells counted is the sum of all cells counted across squares in one chamber. The proportion of the cells counted applies if not all inner squares within a set square are counted (i.e., if only 4 out of the 20 in a corner square are counted, then this term will equal 0.2).

For most applications, the four large corner squares are only used. The cells that are on or touching the top and left lines are counted, but the ones on or touching the right or bottom lines are ignored.[5]

Requirements

The original suspension must be mixed thoroughly before taking a sample. This ensures the sample is representative, and not just an artifact of the particular region of the original mixture it was drawn from.

An appropriate dilution of the mixture with regard to the number of cells to be counted should be used. If the sample is not diluted enough, the cells will be too crowded and difficult to count. If it is too dilute, the sample size will not be enough to make strong inferences about the concentration in the original mixture.

By performing a redundant test on a second chamber, the results can be compared. If they differ more than 2 times the counting error (square root of the count[6]), the method of taking the sample may be unreliable (e.g., the original mixture is not mixed thoroughly).

The counting chamber should be filled by capillary action after the chamber lid (special cover-slip with certified thickness and flatness) has been put in place. This avoids the risk that the cells could sediment/stick to the glass or some volume to evaporate before the cover-slip is placed on top and resulting in an overestimation of the cell concentration. Sedimentation is less of a problem with bacteria but evaporation, more prevalent in low-humidity air-conditioned laboratories, still has to be minimized.

Applications

- Blood counts: for patients with abnormal blood cells, where automated counters don't perform well.

- Sperm counts

- Cell culture: when subculturing or recording cell growth over time.

- Beer brewing: for the preparation of the yeast.

- Phytoplankton cell counting

- Cell processing for downstream analysis: accurate cell numbers are needed in many tests (PCR, flow cytometry), while some others require high cell viability.

- Measurement of cell size: in a micrograph, the real cell size can be inferred by scaling it to the width of a hemocytometer square, which is known.[7]

References

- Absher, Marlene (1973). "Hemocytometer Counting": 395–397. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-427150-0.50098-X. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Fig. 8. Views of an improved Neubauer hemocytometer slide. (A) Top view..." ResearchGate. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Hemocytometer: square sizes".

- "Basic Hemocytometer usage".

- Strober W (2001). "Monitoring cell growth". In Coligan JE, Bierer BE, Margulies DH, Sherach EM, Strober W (eds.). Current Protocols in Immunology. 5. USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. A.2A.1. doi:10.1002/0471142735.ima03as21.

- Shapiro, Howard (31 January 2001). "very rare events: how low can you go?".

- "Measuring cell size with a hemocytometer". Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

External links

- Online exercise - Yeast counts in Neubauer improved or Thoma counting chambers

- Hemocytometer calculator online