HMS Sans Pareil (1794)

HMS Sans Pareil ("Without Equal") was an 80-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy. She was formerly the French ship Sans Pareil, but was captured in 1794 and spent the rest of her career in service with the British.

.jpg) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Sans Pareil |

| Builder: | Brest |

| Laid down: | August 1790 |

| Launched: | 8 June 1793 |

| Captured: | 1 June 1794, by the Royal Navy |

| Name: | HMS Sans Pareil |

| Acquired: | 1 June 1794 |

| Reclassified: |

|

| Fate: | Broken up, October 1842 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Tonnant-class 80-gun ship of the line |

| Displacement: | 1800 tonnes |

| Tons burthen: | 2190 (bm) |

| Length: | 59.3 metres (197 ft 6 in, gun deck length) |

| Beam: | 15.3 metres 5(0 ft 7 in) |

| Draught: | 7.8 metres |

| Depth of hold: | 7.2 m (23 ft 7 in) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Complement: | 738 |

| Armament: |

|

French service

Sans Pareil was built at Brest as a Tonnant-class ship of the line, to a design by Groignard. She was launched on 8 June 1793, but spent less than a year in service with the French navy.[1] She sailed into the Atlantic in May 1794, under the command of Captain Courand, as part of a squadron under Rear-Admiral Joseph-Marie Nielly. She was Nielly's flagship for the operation, which aimed to meet a corn convoy inbound from North America, under Pierre Jean Van Stabel. Neilly initially failed to make contact with the French convoy, but on 9 May 1794 the squadron came across a British one, escorted by HMS Castor, under the command of Captain Thomas Troubridge.[1] The squadron attacked and captured Castor, and a number of the convoy's ships. Castor was only briefly in French hands before HMS Carysfort retook her on 29 May.[1] However, Troubridge remained a prisoner on Sans Pareil until the battle of the Glorious First of June.[3]

In May, Sans Pareil captured a number of British merchantmen: Gordon, Boyman, master, sailing from Antigua to London; Irton, Wikinson, master, sailing from Cork to Jamaica; Edward, of London, sailing from Naples to Hull; and Active, sailing from Civita Vechia to Lieth.[4][Note 1] The same report credits Sans Pareil with capturing HMS Alert, though the actual captor was Unité.[6]

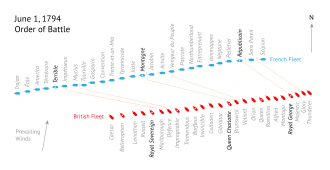

Having made contact with the approaching convoy, the squadron began the return voyage. During this, a French fleet under Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse was intercepted by a British fleet under Lord Howe, and a series of sporadic actions took place on 28 and 29 May. Neilly brought some of his larger ships, including Sans Pareil, to join Villaret, sending the convoy on ahead under the escort of frigates.

The fleets eventually clashed in force at the Glorious First of June, where Sans Pareil formed part of the French rear. During the battle HMS Royal George, flagship of Vice-Admiral Alexander Hood, broke the French line ahead of Sans Pareil, bringing down her fore and mizzen masts with a broadside. HMS Glory then passed across her stern, shooting away her main mast. Disabled and unmanageable, Sans Pareil drifted out of the line until HMS Majestic captured her. Aboard her were found Troubridge and 50 men and officers of the Castor. They were released and helped to bring the damaged Sans Pareil into Spithead. Sans Pareil had possibly lost as many as 260 of her crew killed, with another 120 wounded.

British service

Sans Pareil was commissioned into the Royal Navy, and was initially commanded from March 1795 by Captain Lord Hugh Seymour, who was promoted to Rear-Admiral on 1 June 1795, the first anniversary of the Glorious First. He was succeeded in the command by Captain W. Browell in August 1795, but she continued to serve as Seymour's flagship, with the Channel Fleet. She was then present as part of a fleet under Admiral Hood at another engagement with Villaret, the Battle of Groix on 22 June, where she engaged the French ships Formidable and Peuple, losing ten killed and two wounded. Formidable was subsequently taken, joining the Royal Navy as HMS Belleisle. Seymour left the ship after this, being appointed to the Board of Admiralty in autumn 1795.

Sans Pareil continued to sail off the French coast, using her French build to her advantage by flying the French ensign and luring privateers to come within range. Seymour returned on a number of occasions, retaining her as his flagship for several cruises. By January 1799 Captain Atkins had taken command of Sans Pareil, but by August Captain Charles Penrose had replaced him. She then sailed to the West Indies, again as Seymour's flagship.

At some point in 1800 or 1801, Sans Pareil captured Guachapin, which the British took into service under that name.[7] The London Gazette reports that on 9 April 1800, Sans Pareil captured the Spanish trader Guakerpin, of 165 tons burthen (bm), ten guns and 38 men. She belonged to Saint Andero, and was sailing from there to Vera Cruz with a cargo of iron, porter, and linens.[8]

On 27 March, Sans Pareil captured two small French privateer schooners. One was Pensee, of four guns and 65 men. She was from Guadeloupe and had set out on cruise from Pointe-à-Pitre when she was captured. The second was Sapajon, of six guns and 48 men. Both were from Guadeloupe and had set out on cruise from Pointe-à-Pitre when they was captured.[8]

Seymour contracted a fever and died on 11 September 1801. Penrose too became ill and had to return to Britain. Sans Pareil then came under the command of Captain William Essington, and served as the flagship of Admiral Richard Montague. She returned to Plymouth on 4 September 1802.

Fate

After her return to Plymouth the Lords of the Admiralty wished immediately to recommission her as a guardship, but then she was put into ordinary instead because she was so in need of repair.[9] In 1805 she was ordered repaired.[10] The subsequent major refit lasted for 18 months and cost £35,000. This turned her into a prison hulk, and by 1807 she was used to hold French prisoners-of-war. She was reduced to a sheer hulk at Plymouth in October 1810, and spent another 32 years in service. Sans Pareil was finally broken up in October 1842.[11]

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

- A few days later the British later recaptured Active, sending her into Hoylake.[5]

Citations

- Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 205.

- Ralfe (1828), p. 309.

- Lloyd's List. n° 2621. - Accessed 23 July 2016.

- Lloyd's List. n° 2622. - Accessed 23 July 2016.

- Hepper (1994), p. 76.

- Marshall (1828), Supplement 2, pp. 461-462.

- "No. 15295". The London Gazette. 20 September 1800. p. 1084.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 8, pp. 260-261.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 14, p. 71.

- Lyon & Winfield. The Sail and Steam Navy List. pp. 9–10.

References

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Hepper, David J. (1994). British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail, 1650-1859. Rotherfield: Jean Boudriot. ISBN 0-948864-30-3.

- Lavery, Brian (2003) The Ship of the Line — Volume 1: The development of the battlefleet 1650–1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- Lyon, David and Winfield, Rif, The Sail and Steam Navy List, All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889, pub Chatham, 2004, ISBN 1-86176-032-9

- Marshall, John (1823–1835) Royal naval biography, or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea officers at the commencement of the present year 1823, or who have since been promoted ... (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown).

- Ralfe, James (1828) The naval biography of Great Britain: consisting of historical memoirs of those officers of the British navy who distinguished themselves during the reign of His Majesty George III. (Whitmore & Fenn).

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1844157006.