HMS Mosquidobit (1813)

HMS Mosquidobit (sometimes Musquedobet or Musquidobit) was the Chesapeake-built six-gun schooner Lynx that the British Royal Navy captured and took into service in 1813. She was sold into commercial service in 1820 and nothing is known of her subsequent fate.

Modern replica of Lynx off Morro Bay, 2007 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Lynx |

| Builder: | Thomas Kemp, Fells Point, Baltimore |

| Completed: | 1812 |

| Commissioned: | 14 July 1812 (Comm. #325) |

| Stricken: | 13 April 1813 |

| Fate: | Captured by the Royal Navy |

| Name: | Mosquidobit |

| Acquired: | By capture 13 April 1813 |

| Fate: | Sold 13 January 1820 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Type: | Topsail schooner |

| Tons burthen: | 22392⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 24 ft 0 in (7.3 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 10 ft 3 in (3.1 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sail |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

Lynx

Owner-investors James Williams, Amos Williams and Levi Hollingsworth commissioned the noted shipbuilder Thomas Kemp to build them a schooner. Lynx was built at Fells Point, Baltimore during the opening days of the War of 1812. She was commissioned on 14 July under captain Elisha Taylor.

Lynx was a bit larger than the typical swift pilot boats after which Kemp modeled her. Kemp had increased her size to 97 feet (30 m) long by 24 feet (7.3 m) wide and 225 tons burthen (bm). She was fitted out as a trader though she carried a crew of 40 men and was armed with six 12-pounder long guns. She cost a little under $10,000.

Lynx was a letter of marque costing the owners $34,000 to secure the L of M. That is, she was an armed merchantman with the warrant to take as prizes enemy merchantmen during the normal course of business, should the opportunity arise. As a merchantman, her crew received a regular wage; they did not depend on prizes for their income.

Lynx served as a merchantman for less than a year. She made one voyage, to Bordeaux, France, and returned with a cargo of luxury goods. She was waiting with three other schooners to run the British blockade for a second voyage when the British captured her.

Battle of Rappahannock River

On 13 April 1813, Sir John Borlase Warren's squadron, consisting of San Domingo, Marlborough, Maidstone, Statira, Fantome, Mohawk and Highflyer blockaded four schooners in the Rappahannock River. The British sent a cutting out expedition in boats 15 miles upriver to capture the schooners at anchor.[2] The attacking British boats carried 105 men led by Lt. James Polkinghorne while the crews of the schooners numbered 160 in all.

Lynx and Arab quickly surrendered at the beginning of the attack.[3] Racer put up more resistance. The last schooner to be taken was Dolphin, which had been on a privateering cruise and consequently carried 100 men and 12 guns.[4] Under her captain, W.S. Stafford, she fought for about two hours before she struck. Stafford placed his losses at six killed and ten wounded.[5] American newspapers reported that the British lost 19 killed and forty wounded.[6] However, Polkinghorne's official report at the time gave his losses as two killed and 11 wounded.[2]

The British took three of the schooners into service. Lynx became Mosquidobit. Racer, of six guns, became Shelburne; Dolphin retained her name.[7] Lastly, it is not clear what became of Arab, of seven guns, which too had put up some resistance.[4] It was difficult for the British to free Arab and though they eventually succeeded, the vessel was apparently badly damaged and was not commissioned for British service. She was taken to Halifax where the Vice-Admiralty Court condemned her.[8] In July 1814, prize money remitted from Halifax for Racer, Lynx, Arab and a number of other vessels, was paid.[Note 1]

British service

The Admiralty bought Lynx for £1,933 11s 5d (amended figure) and the British named her for the town of Musquodoboit Harbour, Nova Scotia, commissioning her under Lieutenant John Murray.[1] Mosquidobit joined the British fleet blockading the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay at Lynnhaven Bay (just inside the Virginia Capes). She was subsequently stationed in Nova Scotia. On 30 March 1814 she arrived in Portsmouth.

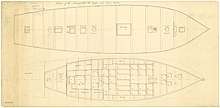

From September 1815 she was under the command of Joseph Giffiths until 1817.[1] Eventually Mosquidobit sailed to Deptford, England where her lines were taken off (surveyed and recorded) on 10 May 1816. She then sailed out of Cork on the Irish station where she served on anti-smuggling duties.

On 15 January 1817 Mosquidobit discovered Eleanor abandoned in the Irish Sea. Mosquidobit towed Eleanor in to Dublin.[10]

On 9 December 1818 Mosquidobit sent into Dublin the Dutch cutter Thetis, of Flushing. Mosquidobit had encountered Thetis off the Irish Coast and captured her after a long pursuit. Almost a year later, on 8 December 1819, Mosquidobit received a reward from the Custom-House, Dublin, for the second largest number of smugglers taken on the coast of Ireland, in the year ending 1 Oct 1819.[11] Griffiths paid her off in December; he was promoted to the rank of Commander in August 1819.[12]

She was paid-off again in July 1819 but then reportedly served in the Mediterranean, sailing between Toulon and Marseilles.

Fate

By 1820, she had been decommissioned and on 13 January 1820, a Mr. Rundle purchased her for £410 and placed her in private service.[1] Nothing more is known of her.

Commemoration

A full scale sailing replica of this schooner, the tall ship Lynx, was built at Rockport, Maine in 2001 by Woods Maritime under President Woodson K Woods, and then operated in California. Her home is now Nanntucket, Ma transferring from port of registry previously Portsmouth, N.H. Lynx now sails the eastcoast from Maine to St Petersburg, Fl frequenting ports of Boothbay Harbor, Maine - Nantucket, Ma - Martha's Vineyard - Annapolis, MD - St Simons Island, Ga - and Tall Ship Event ports of call.

A model of the schooner as HMS Musquidobit is on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Note, citations, and references

Notes

- For Racer, Lynx, Arab, and Flight, the share of a petty officer was £6 1s 10½d; for an able seaman it was £2 0s 7½d.[9]

Citations

- Winfield (2008), p. 368.

- "No. 16732". The London Gazette. 22 May 1813. p. 995.

- Roosevelt (1901), p. 98.

- Chapelle (1967), p. 214.

- Maclay (1899), p. 467.

- Scott (1834).

- Dudley (1992), p. 339.

- U.S. vessels adjudged at Halifax

- "No. 16921". The London Gazette. 30 July 1814. p. 1541.

- "The Marine List". Lloyd's List (5145). 21 January 1817.

- "No. 17719". The London Gazette. 26 June 1821. p. 1353.

- O'Byrne (1849), p. 434.

References

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1967) The search for speed under sail, 1700-1855. (New York: Norton).

- Dudley, William S. (1992) The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Center), V. 2.

- Footner, Geoffrey M. (1998) Tidewater Triumph: The Development and Worldwide Success of the Chesapeake Bay Pilot Schooner. (Naval Institute Press). ISBN 9780913372807

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1899) A history of American privateers. (London & New York).

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849) A naval biographical dictionary: comprising the life and services of every living officer in Her Majesty's navy, from the rank of admiral of the fleet to that of lieutenant, inclusive. (London: J. Murray), Vol. 1.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1901) "The War with the United States" in William Laird Clowes ed. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. (London: Sampson, Lowe Marston & Co.), Vol. 6.

- Scott, Sir James (1834). Recollections of a naval life, Volume 3. London, England: R. Bently Publishing.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Phillips, Michael. Ships of the old Navy