HMS Baralong

HMS Baralong, also known as HMS Wyandra[4] was a Royal Navy warship that was active during World War I. She was a "Special Service Vessel" (also known as a Q-ship) whose function was to act as a decoy, inviting attack by a U-boat in order to engage and (if possible) destroy it. Baralong was successful on two occasions in her career, sinking U-27 in August 1915, and U-41 in September 1915; however both these actions caused controversy, particularly the first, being referred to as the Baralong incidents.

HMS Baralong | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Baralong |

| Builder: | Armstrong Whitworth & Co, Low Walker [1] |

| Launched: | 12 September 1901[1] |

| Commissioned: | April 1915 |

| In service: | 1915-1916 |

| Fate: | de-commissioned Nov 1916 |

| Notes: | Converted to Q-Ship at Barry Docks |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | cargo liner |

| Tonnage: | 4192 grt[2] |

| Length: | 360 ft (110 m)[3] |

| Beam: | 47 ft (14 m)[3] |

| Height: | 28.347 ft (8.640 m)[3] |

| Propulsion: | steam triple expansion[3] |

| Speed: | 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament: | 3 × 12-pounder naval guns |

Early career

Baralong was built in 1901 as a "three-island" steam cargo liner and had an uneventful peacetime career with Bucknall Steamship Lines (later Ellerman & Bucknall Line)[5] before the start of World War I. Initially requisitioned by the Royal Navy in August 1914 as a supply ship, in 1915 she was commissioned into a special service vessel. She was armed with three 12-pounder guns in concealed mountings, equipped with devices for simulating damage, and other modifications fitting her for her role.[6] She was manned by a volunteer crew and commanded by Cdr Godfrey Herbert, an experienced submariner in the role of "poacher turned gamekeeper". The work was carried out at Barry Docks and was completed in April 1915.[7]

First action

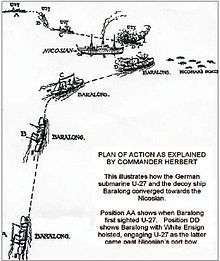

Baralong spent the next four months patrolling the Southwest Approaches, seeking to invite a U-boat attack. On 19 August 1915 she received a distress call from the passenger liner Arabic which was under attack, and headed towards the location in an attempt to engage the U-Boat responsible. After several hours she encountered the British steamer Nicosian, which was carrying munitions and mules, and under fire from a German U-boat, U-27. At the time Baralong was flying the neutral US flag and closed with Nicosian, signalling she intended to pick up survivors. As she approached, U-27 passed behind the stern of Nicosian. Herbert had Baralong’s guns cleared away, and the flag replaced with the White Ensign whilst she was obscured from view; when U-27 emerged from behind the bow of Nicosian she was met with a hail of gunfire. Baralong scored 34 hits with her main battery, as well as machine gun and small arms fire, and U-27’s crew abandoned ship as the U-boat sank. Baralong manoeuvred to pick up Nicosian's crew, while the men from U-27 made for Nicosian in order to board her. Baralong’s men fired on them, killing most as they swam or climbed to Nicosian's deck. A party of Germans who gained the deck disappeared below, and Baralong landed a boarding party that pursued and killed them, either as combantants or prisoners [Admiralty Lord Winston Churchill had given orders that German submariners could be treated as felons rather than prisoners of war].[8] When some American members of Nicosian’s crew (mostly employed as muleteers) returned to the US the story became known, and the German government alleged the Baralong’s crew had committed an atrocity.[9] The dispute continued for some time, and became known as the Baralong Incident.

Second action

In September 1915, now under the command of Lt. Cdr. A. Wilmot-Smith (Herbert having returned to the submarine service) Baralong was again on patrol in the Southwest Approaches when she fell in with the steamship Urbino, which was under attack by U-41. As Baralong approached U-41 dived, surfacing when Baralong had drawn closer and ordering her to stop. Wilmot–Smith slowed and started to launch a boat in compliance as the U-boat came closer, but at 700 yards he swung to starboard and Baralong opened fire. Her first shots wrecked U-41’s conning tower, and killed her commander. The U-boat dived, but quickly re-surfaced; her crew started to abandon ship, but only two men escaped before the U-boat sank. Baralong then picked up Urbino’s crew and also the two German submariners. One of these, U-41's first officer O/L I.Crompton, was severely wounded, and was repatriated to Germany; once there he made a series of allegations which were published in Germany, including that Wyandra had fired on and sunk the U-boat without striking the American flag. This would have been a violation of the rules of war; while the use of a False Flag was allowed,[10] it was required that a belligerent identify itself before initiating hostilities.

The event generated widespread outrage in Germany, especially among Kriegsmarine officers, and referred to there as the 'Second Baralong Incident'. The sinking was also commemorated in a propaganda medal designed by the German medallist Karl Goetz. The British Admiralty denied the accusations, and unlike the first incident had little currency outside Germany itself.

Later career

Following this success Baralong, now HMS Wyandra, was transferred to the Mediterranean to join the Q-ship force being established there. She continued in this role but had no further success, and in November 1916 returned to civilian service. Baralong was one of the first Q-Ships operational, and one of the most successful. She and her commanders, particularly Herbert, were instrumental in establishing Q-Ship procedures for the remainder of the Allied anti-submarine campaign.

Wyandra returned to Ellerman & Bucknall Line in 1916 under the name Manica. She was sold to Japan in 1922, sailing under the names Kyokuto Maru and Shinsei Maru No.1 until being scrapped in Japan in 1933.[1]

Notes

- "Baralong". Miramar Ship Index (subscription). Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Ritchie p176

- Maru No. 1 "Lloyd's Register" Check

|url=value (help). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 8 December 2012. - Gazette 31972 - 9 July 1920

- "Ellerman & Bucknall". The Ships List. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Colledge, J J (1970). Ships of the Royal Navy: An historical index, Vol 2. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. ISBN 0715343963.

- Ritchie p33

- Haste, Cate (1977). Keep the Home Fires Burning: Propaganda in the First World War. London: Allen Lane. p. 99. ISBN 9780713908176.

- "Memorandum of the German Government...and reply of His Majesty's Government thereto". WWW Virtual Library. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- deHaven-Smith, Lance (2013). Conspiracy Theory in America. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 225.

References

- Chatterton, E Keble : Q-Ships and their story. (1922) ISBN (none)

- Halpern, Paul : A Naval History of World War I (1995) ISBN 1-85728-498-4

- Kemp, Paul : U-Boats Destroyed ( 1997) ISBN 1-85409-515-3

- Messimer, Dwight Find and Destroy (2001) ISBN 1-55750-447-4

- Ritchie, Carson : Q-Ships. (1985) ISBN 0-86138-011-8

- Tarrant, VE : The U-Boat offensive 1914-1945 (1989) ISBN 0-85368-928-8