HAT-P-11b

HAT-P-11b (or Kepler-3b) is an extrasolar planet orbiting the star HAT-P-11. It was discovered by the HATNet Project team in 2009 using the transit method, and submitted for publication on 2 January 2009.

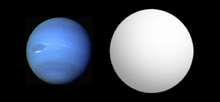

Size comparison of Neptune with HAT-P-11b (gray). | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Bakos et al. |

| Discovery site | Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Discovery date | 2 January 2009 |

| Transit (HATNet) | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Apastron | 0.0637+0.0020 −0.0019 AU |

| Periastron | 0.0413+0.0018 −0.0019 AU |

| 0.05254+0.00064 −0.00066 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.218+0.034 −0.031[2] |

| 4.887802443+0.000000034 −0.000000030[3] d | |

| Inclination | 89.05+0.15 −0.09[3] |

| 2454957.15+0.17 −0.20[2] | |

| 19+14 −16[2] | |

| Semi-amplitude | 10.42+0.64 −0.66[2] |

| Star | HAT-P-11 |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 4.36±0.06[3] R⊕ |

| Mass | 23.4±1.5[2] M⊕ |

Mean density | 1,440 kg/m3 (2,430 lb/cu yd) |

| 1.20 g | |

This planet is located approximately 123 light-years (38 pc) away[4]

Discovery

The HATNet Project team initially detected the transits of HAT-P-11b from analysis of 11470 images, taken in 2004 and 2005, by the HAT-6 and HAT-9 telescopes. The planet was confirmed using 50 radial velocity measurements taken with the HIRES radial velocity spectrometer at W. M. Keck Observatory.[1]

At the time of its discovery HAT-P-11b was the smallest radius transiting extrasolar planet discovered by a ground based transit search and was also one of three previously known transiting planets within the initial field of view of the Kepler spacecraft.[1]

There was a linear trend in the radial velocities indicating the possibility of another planet in the system.[1] This planet, HAT-P-11c, was confirmed in 2018.[2]

Characteristics

This planet orbits about the same distance from the star as 51 Pegasi b is from 51 Pegasi, typical of transiting planets. However, the orbit of this planet is eccentric, at around 0.198, unusually high for hot Neptunes. HAT-P-11b's orbit is also highly inclined, with a tilt of 103+26

−10°.[5] degrees relative to its star's rotation.[6][7]

The planet fits models for 90% heavy elements. Expected temperature is 878 ± 15K.[1] Actual temperature must await calculations of secondary transit.

On 24 September 2014, NASA reported that HAT-P-11b is the first Neptune-sized exoplanet known to have a relatively cloud-free atmosphere and, as well, the first time molecules, namely water vapor, of any kind have been found on such a relatively small exoplanet.[8] In 2009 French astronomers observed what was thought to be a weak radio signal coming from the exoplanet. In 2016 scientists from the University of St Andrews set out to solve the mystery. They assumed that the signal was real and was coming from the planet and investigated whether it can be produced by lightning on HAT-P-11b. Assuming that the underlying physics of lightning is the same for all Solar System planets, like Earth and Saturn, as well as on HAT-P-11b, the researchers found that 3.8 × 10^6 lightning flashes of Saturnian lightning-strength in a square kilometre per hour would explain the observed radio signal on HAT-P-11b. This storm would have been so enormous that the largest thunderstorms on Earth or Saturn would have produced <1% of the strength of the signal coming from the planet.[9][10]

See also

- Gliese 436 b

- HATNet Project

- HAT-P-7b

- Kepler Mission

References

- Bakos, G. Á.; et al. (2010). "HAT-P-11b: A Super-Neptune Planet Transiting a Bright K Star in the Kepler Field". The Astrophysical Journal. 710 (2): 1724–1745. arXiv:0901.0282. Bibcode:2010ApJ...710.1724B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/710/2/1724.

- Yee, Samuel W.; et al. (2018). "HAT-P-11: Discovery of a Second Planet and a Clue to Understanding Exoplanet Obliquities". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (6). 255. arXiv:1805.09352. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..255Y. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aabfec.

- Huber, K. F.; Czesla, S.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M. (2017). "Discovery of the secondary eclipse of HAT-P-11 b". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 597. A113. arXiv:1611.00153. Bibcode:2017A&A...597A.113H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629699.

- Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- Obliquities of Hot Jupiter host stars: Evidence for tidal interactions and primordial misalignments, 2012, arXiv:1206.6105

- "Inclined Orbits Prevail in Exoplanetary Systems". 12 January 2011.

- Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda; Josh N. Winn; Daniel C. Fabrycky (2012). "Starspots and spin-orbit alignment for Kepler cool host stars". Astronomische Nachrichten. 334 (1–2): 180–183. arXiv:1211.2002. Bibcode:2013AN....334..180S. doi:10.1002/asna.201211765.

- Clavin, Whitney; Chou, Felicia; Weaver, Donna; Villard; Johnson, Michele (24 September 2014). "NASA Telescopes Find Clear Skies and Water Vapor on Exoplanet". NASA. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Could ferocious lightning storms beam radio signals to Earth?". 26 April 2016.

- Hodosán, G.; Rimmer, P. B.; Helling, Ch. (2016). "Lightning as a possible source of the radio emission on HAT-P-11b". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. ADS. 461 (2): 1222–1226. arXiv:1604.07406. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.461.1222H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw977.

External links

![]()

- "HAT-P-11 b". Exoplanets. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2009.