Hôtel-Dieu, Paris

The Hôtel-Dieu (French pronunciation: [otɛldjø]) is a hospital located on the Île de la Cité in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, on the parvise of Notre-Dame. It was supposedly founded by Saint Landry in 651 AD,[1] making it the oldest hospital in the city and the oldest worldwide still operating. The Hôtel-Dieu was the only hospital in the city until the Renaissance. While the old Hôtel-Dieu stood by the Seine on the opposite side of the parvise, it was ravaged by fire several times, and was rebuilt for the last time at its present location between 1867 and 1878, as part of Haussmann's renovation of Paris.

| Hôtel-Dieu | |

|---|---|

| Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris | |

View of the Hôtel-Dieu from the Tour Saint-Jacques | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | 1 Parvis Notre-Dame – Place Jean-Paul-II 75004 Paris, France |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Public |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes |

| Beds | 349 |

| History | |

| Opened | 829 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

| Lists | Hospitals in France |

Nowadays operated by Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), the Hôtel-Dieu is also a teaching hospital associated with the Faculté de Médecine Paris-Descartes.

History

The old Hôtel-Dieu

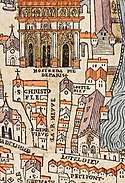

The Hôtel-Dieu was supposedly founded by Saint Landry in 651 AD, but its first recorded mention only dates back to 829.[1] It is nonetheless considered to be the oldest hospital in the city[2] and the oldest worldwide still operating.

The history of Parisian hospitals dates from the Middle Ages. Poverty was widespread during that period, and the Hôtel-Dieu became an opportunity for many of the bourgeois and nobility to come to its aid. Their efforts allowed the construction of the Hôpital de la Charité, which linked piety and medical care. Like many hospitals of that era, it started as a general institution catering for the poor and sick, offering food and shelter in addition to medical care.[3][4] The creation of the Hôtel-Dieu continued this tradition of charity up until the 19th century, despite being called into question during the centuries which followed.

In the 16th century the Hôtel-Dieu faced a financial crisis, as it was financed only by help, subsidies or privileges. This brought about the creation in 1505 of a council of laymen governors:[2] the Presidents of Parliament, the Chambre des Comptes, the Cour des Aides and the Prévôt des Marchands. during the same century, Henry IV built Hôpital Saint-Louis to unclog the Hotel Dieu.

The 17th century elite created establishments to house the poor. Hospitals thus took the name of "Hôpital Général" (General hospital) or "Hôpital d'enfermement" (Asylum), of which the Hôtel-Dieu was one. The centralized approach to extreme poverty in France was based on the premise that medical care was a right for those without family or income, and formalized the admission process in hospitals to prevent overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.[5] The Lieutenant Général de Police became a member of the Bureau de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Paris (Bureau for the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris) in 1690. The hospital extended across the river with building of the Rosary House surmounting the Pont au Double.[6]

In the 18th century, Paris hospitals in general were characterized with poor sanitation and treatment followed by high mortality rate. As Jacques Tenon would note in his Mémoires sur les hôpitaux de Paris (1788), the sanitary conditions were horrendous, facilities were overcrowded and there was a high mortality rate in these hospitals. The Hôtel-Dieu was "the most unhealthy and uncomfortable of all hospitals", with a mortality rate of almost 25 percent. Even though it was the largest of Paris' hospitals with 1,200 beds, many beds held three or more patients—women gave birth in shared beds and there was no separation amongst patients with contagious diseases.[7] The 1,200 beds in the hospital were completely inadequate for housing its over 3,500 patients.[8]

In 1772 a fire destroyed a large part of the Hôtel-Dieu.[3] This event sparked discussions over the conditions and possible reforms that would be made to the hospital system.[9][lower-alpha 1] Louis XV ordered the demolition of the Hôtel-Dieu in 1773 after hearing of its poor patient conditions. The execution of the order was however delayed due to the King's death, and Louis XVI, who succeeded him, was persuaded of an alternate plan to reconstruct the damaged parts of the hospital. This scheme was submitted to the Academy of Sciences for review, and debate regarding Hôtel-Dieu extended until 1785 as it transformed into discussions about the reformation of Paris's hospital system.[10] Conditions enhanced in 1787, when the Hôtel-Dieu implemented a code of medical services that shifted the hospital from a curing machine run by nuns to a medical and surgical establishment run by doctors.[8] Jacques Necker created the positions of Inspecteur général des hôpitaux civils et des maisons de force (General Inspector for civil hospitals and jails) and Commissaire du roi pour tout ce qui a trait aux hôpitaux (Royal Commissioner for all that relates to hospitals).

In the meantime, the Hôtel-Dieu had received a high status as a surgical training institution with the appointment of Pierre-Joseph Desault as chef de service in 1785. Desault established an elaborate educational program for surgical interns when previously they had only informal training.[11] By the 19th century hospitals had become places of teaching and medical research in addition to practicing medicine. Xavier Bichat, a pupil of Desault, expounded on his new "membrane theory" during a course taught in 1801–1802 at the Hôtel-Dieu.[12]

In 1801, the Parisian hospitals adopted a new administrative framework: the Conseil général des hôpitaux et hospices civils de Paris (General Council for Parisian hospitals and civil hospices). This willingness to improve management brought about the creation of new services: the Bureau d'admission (Admissions office) and the Pharmacie centrale (Central Pharmacy). Napoleon I finally rebuilt the portions of the Hôtel-Dieu which had burnt in 1772.[3] Also during this period, the Hôtel-Dieu advocated the practice of vaccination, of which Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt was a fervent supporter. Similarly, the discoveries of René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec permitted the refinement of methods of diagnosis, auscultation, and aetiology of illnesses. The Pont au Double was demolished in 1847 and rebuilt without covering.

Present Hôtel-Dieu

The Hôtel-Dieu was rebuilt between 1867 and 1878 on the opposite side of the parvise of Notre Dame, as part of Haussmann's renovation of Paris commissioned by Napoleon III. The reconstruction followed plans by architects Gilbert and Diet.

It was not until 1908 that the Augustinian nuns left the Hôtel-Dieu for good.

Role within the Parisian healthcare system

The Hôtel-Dieu is the top casualty centre to deal with emergency cases, being the only emergency centre for the first nine arrondissements and being the local centre for the first four.[3][13]

For the last 50 years it has been home to the diabetes and endocrine illnesses clinical department. It deals almost exclusively with the screening, treatment and prevention of the complications associated with diabetes mellitus. It is also a referral service for hypoglycemia. Oriented towards informing the patient (therapeutic education) and technological innovation, it offers a large choice of care facilities for all levels of complications. It is also at the forefront of research in diabetes in areas such as new insulins and new drugs, effects of nutrition, external and implanted pumps, glucose sensors and artificial pancreas.

More recently, a major department for ophthalmology (emergencies, surgery and research) has been developed at the Hôtel-Dieu, under the supervision of Yves Pouliquen.

Notable figures

Notable physicians, researchers, and surgeons who practised at the hospital include Forlenze, Bichat, Dupuytren, Hartmann, Desault, Récamier, Cholmen, Dieulafoy, Trousseau, Ambroise Paré, Marc Tiffeneau.

Notes

- The ideas advocated by the Age of Enlightenment also allowed reflection on hospitals.

References

- New Catholic encyclopedia. 7. p. 127.

- Radcliff, Walter. Milestones in Midwifery and the Secret Instrument. Norman Publishing.

- "Hotel Dieu". London Science Museum. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Fosseyeux, Marcel. "L'Hôtel-Dieu de Paris au XVII et au XVIIIe siècle" (in French). Berger-Levrault.

- Risse, Guenter B. (1999). Mending bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 301–302. ISBN 0-19-505523-3.

However, the Committee also realized that there were other good poor persons without family support for whom the hospital remained a necessary destination during illness. For such individuals, hospital care was to be a right"; "By restricting assistance to the truly needy, deinstitutionalization would also save money and curtail waste in the hospitals themselves. Equally important, this plan would prevent overcrowding and thus improve institutional hygiene.

- New Catholic encyclopedia. 7. p. 139.

- Bynum, W.F. (1994). Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9780521272056.

- Risse, Guenter (1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 298. ISBN 0-19-505523-3.

- Risse, Guenter B. "Mending Bodies, Saving Souls". Oxford University Press. p. 295.

- Risse, Guenter (1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 0-19-505523-3.

- Risse, Guenter (1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 325. ISBN 0-19-505523-3.

- Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. 1999. p. 312.

- "AP-HP Hôtel-Dieu official site" (in French).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hôtel-Dieu de Paris. |

- Official website (in French)

- Hotel Hospital Dieu concepção artística do East Villa Graphics Jun. 2012