Gungunhana

Ngungunyane, also known as Mdungazwe Ngungunyane Nxumalo, N'gungunhana, or Gungunhana Reinaldo Frederico Gungunhana, (c. 1850 – 23 December 1906) was a tribal king and vassal of the Portuguese Empire, who rebelled, was defeated by General Joaquim Mouzinho de Albuquerque and lived out the rest of his life in exile, first in Lisbon, but later on the island of Terceira, in the Portuguese Azores.

Gungunhana was the last dynastic emperor of the Empire of Gaza, a territory now part of Mozambique. Nicknamed the Lion of Gaza, he reigned from around 1884 to 28 December 1895, the day he was imprisoned by Joaquim Mouzinho de Albuquerque in the fortified village of Chaimite. Because he was already known to the European press, the Portuguese colonial administration decided to exile him, rather than send him to face a firing squad, as would normally be the case. He was transported to Lisbon, accompanied by his son Godide and other dignitaries. After a brief stay, he was transferred to the Azores, where he would die eleven years later.

Biography

Originally given the name, Mdungazwe (defined in Zulu as 'one who confuses the people'), a name he carried until he assumed the throne in 1884, whereupon he would be known as Ngungunhane, he was born around 1850. According to oral tradition, he was born in the territory of Gaza, somewhere between the rivers Zambezi and Incomati, but, very probably, on the banks of the Limpopo River, where the main settlements of the Nguni people then stood. He was the son of Mzila (or Muzila), who was king of Gaza from 1861 to 1884, and Yosio, whose name, after her death, was replaced by Umpibekezana. His father was the son and successor of Soshangane who, as head of an army advancing northward from Zululand, had founded the Gaza Empire.

Early years (1850–1864)

Mundagazi was born into a complex society during a period of great social and political instability. His grandfather, Soshangane (also called Manicusse or Manukosi), was the king (or Nkosi) of a Nguni-speaking people, related to the Swazi, whose ancestral lands were in the territory of present-day South Africa. Soshangane was also the undisputed leader of a powerful army that, following the onset of the Mfecane (The Great Scattering), migrated to the north from Zululand. On their way north, throughout the 1820s and into the 1830s, Soshangane was able to persuade the chiefs of about two hundred tribes to become his vassals. Their ultimate destination, planned or not, was land located between the Maputo and Zambezi rivers. In the process, the Nguni displaced, co-opted, or slaughtered the native peoples. Upon arrival, Soshangane founded an empire to which he gave the name, Gaza (the name of his grandfather). In its initial stages, Gaza had about 56,000 km2 (22,000 sq mi) of land.

With the arrival of the Nguni, the relative quiet that had prevailed among the local peoples and the Portuguese traders, who had established themselves along the Mozambican coast, was rudely broken by a succession of massacres and forced submissions to a new power. This created a climate of insecurity and fear that remained for decades.

Founding of the Gaza Empire

After a walk of nearly twenty years' duration, Soshangane and his people established the center of their power in the valley of the River Limpopo founded the village of Chaimite, and declared it his capital. As the longest-standing European presence in those territories, Portugal decided to send, in August 1840, an embassy to the court of Manicusse. The delegation was led by Ensign Caetano Pinto dos Santos, who had instructions to establish a treaty of friendship, delivering a sword and a sash to the king in exchange for a short spear and a shield. The embassy was received, but Manicusse said that, at the moment, he saw no advantage in a treaty of friendship with the king of Portugal. (This is documented in a report, dated 18 November 1840, submitted by Ensign Caetano Pinto dos Santos and archived by the Registrar of the National Farms in Inhambane, João Caetano Dias.) Even though the sword was exchanged for the short spear, the attacks continued.

So it happened that, in this region, in this social and political context, around 1850, Mundagaz, the future Ngungunhane, a prince of royal blood, the son of Mzila, one of the putative heirs of Manicusse, was born. Educated for the life of a warrior, from an early age participating in the long hikes that his father and grandfather had undertaken annually throughout their vast fields, Ngungunhane was raised to fight and to learn the tactics of war that were his grandfather's legacy.

A dynastic crisis

When Manukuza died in 1858, the competition for the throne pitted Mzila, the father of Mundagazi, and Mawewe, his uncle, against one another. After a brief period of armed strife, Mawewe emerged victorious. He decided, in 1859, to press his advantage by attacking his brothers and their families. Mzila was able to escape to the Transvaal, where he organized an army to overthrow his brother. Mundagaz probably followed his father into exile, escaping the attempt by Mawewe to destroy their lineage.

The Portuguese colonial administration became convinced that Mawewe was likely to be just as aggressive and fractious as his father and predecessor had been, and they, together with their Boer neighbors to the south, and many local tribal leaders, who also felt threatened by the prospect of Nguni domination, decided to unite against him. The president of the Orange Free State, and a number of Boer officials, on 29 April 1861, met with the vice-consul of Portugal, and proposed a formal alliance against Mawewe, a proposal that was accepted with reluctance.

However, these reservations disappeared when Mawewe demanded that the Portuguese colony at Lourenço Marques (now called Maputo) pay tribute in the form of footwear, including a clause that required pregnant Portuguese women to pay a double tribute. This was backed by a threat that failure to comply would cause Mawewe to undertake a scorched-earth policy against Portuguese interests in the region. Onofre Lourenço de Paiva de Andrade, then governor of Lourenço Marques, responded by sending a rifle cartridge to Mawewe, saying that this would be the form his tribute would take.

Civil war

War was declared, and, on 2 November 1861, Mzila arrived in Lourenço Marques to accept Portuguese support in return for his allegiance. From this point forward, Mzila broadcast his claim to be the rightful king, and the war gained momentum.

The decisive battle was waged in late November 1861, along a line of nearly twenty kilometres from the beaches of Matola to the land of Moamba. Despite having fewer men, Mzila won, and, on 30 November, he showed up at the prison in Lourenço Marques, where he was amicably received by the governor.

On 1 December 1861, a treaty was signed, in which it stated that Mzila was a Portuguese subject. A record of this agreement, which was approved by the Portuguese government, was published in the orders of 18 February 1863 by José da Silva Mendes Leal, then Minister of the Navy and Overseas.

A new and decisive victory in battle by Mzila on 16 December 1861 in the Maputo valley, consolidated the alliance. In all, Portugal had provided Mzila two thousand rifles, fifty thousand rounds of ammunition, and twelve hundred flints. In addition, the Portuguese had secured the support of the Boers and undertaken intermediation with local leaders, who preferred to submit to the suzerainty of the distant king of Portugal rather than the local hegemony of Mawewe. All of this accrued to Mzila's benefit.

Although the war lasted until 1864, and the capital of the kingdom was moved from the valley of the Limpopo River to Mossurize, north of the river Save, in the current Mozambican province of Manica, Mzila was gradually mastering the art of controlling the Nguni and its vassals. From 1864 onward, he was the undisputed ruler of the Empire of Gaza. With these events, Mundagaz became a potential successor among the princes, and he began a journey that would lead to power.

The reign of Mzila (1864–1884)

After the war, Mzila devoted himself to the consolidation of his power and the expansion of the Empire of Gaza. He maintained the style of governance of his father, ruling with an iron hand and keeping the habit of walking long distances to keep tabs on all of his domains. The capital remained at Mossurize, and the village of Chaimite, the former capital, became a place of pilgrimage, of memorials devoted to past feats, and a dwelling-place for ancestral spirits.

Despite the treaty signed in 1861 and the effective alliance with the Portuguese that had gained him his throne, the warriors of Mzila ran roughshod over the Portuguese colonies at Sofala and Inhambane several times, and a climate of tension developed that did not accord with the formal agreements and Mzila's frequent expressions of friendship and gratitude.

Competition among the Europeans

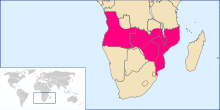

Simultaneously, there was increasing competition in the region among the Europeans: the Portuguese, the English, and the Afrikaners were vying for control of more and more territory. Expeditions of discovery aimed at broadening the European exploitation of Africa were more and more frequent, and there were more and more missionaries and traders visiting the land of Gaza. Lisbon had already started to nourish ambitions of a swath of colonies across southern Africa, from Mozambique on the Indian Ocean to Angola on the Atlantic, all of them colored pink, the traditional color of Portuguese possessions on maps of Africa produced in Europe (see Pink Map).

At the beginning of the 1880s, when the reign of Mzila was approaching its end, competition among the Europeans grew rapidly. Their expeditions into the interior increased in frequency, penetrating more deeply into the territory of Gaza. The pressure on Mzila to permit the exploitation of minerals also grew. Maintaining a policy of striking a strategic balance with Portuguese interests, Mzila, on 27 January 1882, accompanied by two columns of troops, visited Lourenço Marques, to pledge his allegiance and to offer his explanations of the attacks on Sofala and Inhambane. He was received, with all appropriate honors, by the governor, who offered him oxen, rice, and spirits. Soon after, in the middle of that year, Mzila asked for a Portuguese flag so that he could fly it over his camp.

Formal relations with Mzila

The following year, in 1883, Portugal decided to appoint an ambassador to the court of Mzila. The assignment fell to António Maria Cardoso, a man experienced in the region, who was dispatched immediately to the place where Mzila was sojourning, in the neighborhood of Bulawayo, in what is now Zimbabwe. After a long wait to get permission to approach the camp and to be received, António Maria Cardoso managed to secure an audience with Mzila and was well received. The same happened to the captain of artillery, Joaquim Carlos Paiva de Andrada, who went to Manica that year to speak to Mzila.

However, despite the apparently satisfactory relationship with the natives, pressure was rising among the European powers to require that a colonizing power demonstrate its ability to effectively exploit and administer its domains in order to justify the possession of territories in Africa. At this time, given the increasing involvement of other European powers in Africa, Portugal decided to strengthen its presence on that continent by organizing major expeditions of exploration, especially those of Roberto Ivens and Hermenegildo Capelo, aimed at demonstrating the feasibility of an occupation of the interior of Africa.

Of course, Mzila didn’t know that he had entered the last year of his life. Neither did he realize that, thousands of kilometers away, white European diplomats were gathering at the Berlin Conference, where they intended to devise a scheme for sharing Africa among the European powers. When he died in late August 1884, the Europeans were meeting to set rules that would determine the future of Gaza.

The succession

During the reign of Mzila, Mundagaz, his son, the future Ngungunhane, was gradually gaining importance, becoming one of the leading figures of his court. When his father died, Mundagaz was not the legitimate heir of Mzila, a position held by his half-brother, Mafemane, whose mother was the principal wife (nkosicaze). So, he instigated a few fratricidal skirmishes, a tradition of the Nguni, which resulted in Mundagaz removing the crown prince from contention and forcing his other two rivals, Anhana and Mafabaze, to flee into exile.

At the end of 1884, in Mossurize, Mundagaz ascended the Nguni throne, assumed the name, Ngungunhane, the son of the lion, and became the Emperor of Gaza.

Descendants

The descendants of Gungunhana currently reside in South Africa. De jure king Eric Mpisane Nxumalo applied for recognition by the Nhlapo Commission, which was rejected in 2012.[1] Claims of the kingdom's authority over the Tsonga people have also been rejected by Tsonga traditional leaders on the grounds that the Tsonga people have been living outside of the Gaza Kingdom since it was founded in 1820 by Soshangane and have never been part of that Kingdom. History states that the Tsonga people fled before Soshangane and established themselves in the Transvaal, free from any despotic rule. In the Transvaal, the Tsonga people founded new colonies and had no relationship with the Gaza Kingdom at all. When the Tsonga people went to war with their new neighbours, the Venda and the Pedi, the Gaza kingdom did not provide any military support, the Tsonga people fought battles alone, the only military assistance that the Tsonga people received while fighting either the Pedi or the Venda was from their beloved 'White Chief', Joao Albasini, who acted at all times as a paramount chief of the Tsonga in the Transvaal. Joao Albasini supplied the Tsonga people with assault rifles and ammunition to protect themselves against the Pedi and the Venda during times of war with these tribes. Because the Tsonga people were fully armed with assault rifles, neither the Pedi nor the Venda were able to challenge the Tsonga during times of conflict because Joao Albasini, a Tsonga chief, has given assault rifles to more than 2000 Tsonga warriors, these 2000 Tsonga warriors were controlled by Joao Albasini and carried assault rifles day and night. Therefore, neither the Venda nor the Pedi could risk going into war with the Tsonga, for they feared the Tsonga superior weaponry. With Joao Albasini supplying the Tsonga people with ammunition, the Gaza Kingdom became irrelevant and was therefore not useful to the Tsonga at all, the Tsonga people therefore had nothing to do with the Gaza Kingdom at all. The Tsonga people want to continue to live their lives in scattered villages without a supreme King, as they have done for centuries. Currently the Tsonga people are led by chiefs, who are supreme rulers in their villages without a King. The Tsonga villages in South Africa starts from Valdezia in Louis Trichardt and end at Mkhuhlu in Hazyview, which is a distance of 315 km long. It is suggested by the Tsonga that Eric Nxumalo become a paramount chief of his people at Bushbuckridge and leave the Tsonga people alone, they have Chiefs and do not need a King.[2]