Guildhall, Newcastle upon Tyne

The Guildhall is an important civic building in Newcastle upon Tyne. It is a Grade I listed building.[1]

| The Guildhall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Coordinates | 54.96842°N 1.60767°W |

| Built | 1655 |

| Architect | Robert Trollope |

| Architectural style(s) | Classical style |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 14 June 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1120877 |

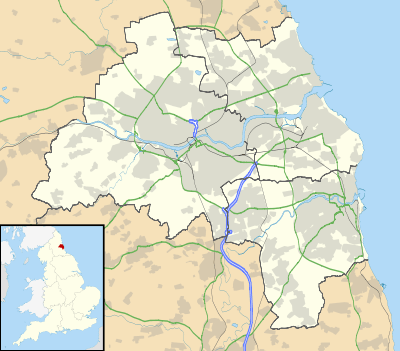

Location of The Guildhall in Tyne and Wear | |

History

The original guildhall, which was commissioned by Roger Thornton, was completed in the early 15th century[2] and had to be demolished after being badly damaged in a fire in 1639.[3]

The new building was designed by Robert Trollope and completed in 1655.[1] Following a poor harvest, the building was attacked by a crowd of 3,000 angry and hungry local people during a riot on 26 June 1740.[4] Fine woodworks, paintings and court records were destroyed and at least one protestor was shot and killed by the military authorities.[4] Five of the alleged ringleaders of the riot were sentenced to seven years of transportation.[5]

By the early 19th century both the north and south elevations had been re-fronted in the classical style.[1] The north elevation, which was re-fronted to the designs of William Newton and David Stephenson in 1794, was given a Palladian style entrance with four Ionic order columns on the first floor.[1] Meanwhile, the south elevation which was re-fronted to the designs of John and William Stokoe in 1809,[6] was given arcading on the ground floor and a Doric order frontage on the first floor.[1]

The old Maison de Dieu, which had been completed by Roger Thornton in 1412, was demolished to make way to an eastern extension to the guildhall to the designs by John Dobson in 1823.[1] The mayor and sheriff were allowed to hold the borough courts in the building[7] and it was also the meeting place of Newcastle Town Council until 1863[8] when the council re-located to larger facilities at Newcastle Town Hall in St Nicholas Square.[9]

The interior of the building features a main hall which is 92 feet (28 m) long and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and has an oak ceiling.[2][10] The "Merchant Venturers' Court" where travellers, sailing in or out of the River Tyne, would meet, contains a large 17th century chimney piece, some fine oak carvings and some religious decorations,[11] while the mayor's parlour is panelled and decorated with local scenes.[1][8]

The guildhall contains a number of paintings by George Bouchier Richardson (1822–1877) of local scenes, including the Entrance to the Side, the Pandon Gate, the old Tyne Bridge, the old Maison de Dieu and the old Exchange.[12]

References

- Historic England. "The Guildhall and Merchants' Court (1120877)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Mackenzie, Eneas (1827). "'Public buildings: The Exchange', in Historical Account of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Including the Borough of Gateshead". Newcastle-upon-Tyne. pp. 215–218. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Timeline: 1248 to 1967". Tyne and Wear Fire and Rescue Service. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Food protesters wreck Newcastle's Guild Hall". Mapping Radical Tyneside. 26 June 1740. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Urban conflict and popular violence: the guildhall riots in 1740 in Newcastle upon Tyne". Cambridge University Press. 1980. pp. 332–349. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Newcastle, Sandhill, Guildhall | sitelines.newcastle.gov.uk". Twsitelines.info. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- Middlebrook, Sydney (1950). Newcastle upon Tyne, Its Growth and Achievement. SR Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-85409-523-3.

- Ford, Coreena (3 February 2016). "Café at Newcastle's Guildhall could be on the horizon as leisure entrepreneur makes plans". The Chronicle. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Town Hall & Corn Market, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England". Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. 1 October 1858. p. 331.

- "Newcastle upon Tyne". Kelly's Directory of Northumberland. 1894. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Guildhall Newcastle upon Tyne 1967". Co-curate. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Newcastle Guildhall". Art UK. Retrieved 2 August 2020.