Gunadhya

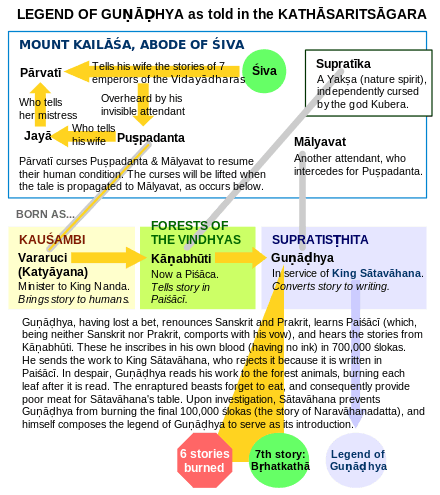

Guṇāḍhya is the Sanskrit name of the sixth-century Indian author of the Bṛhatkathā, a large collection of tales attested by Daṇḍin, the author of the Kavyadarsha, Subandhu, the author of Vasavadatta, and Bāṇabhaṭṭa, the author of the Kadambari.[1] Scholars compare Guṇāḍhya with Vyasa and Valmiki even though he did not write the now long-lost Brihatkatha in Sanskrit; the loss of this text is one of the greatest losses of Indian literature. Presently available are its two Kashmiri Sanskrit recensions, the Brihatkathamanjari by Kshemendra and the Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva.[2]

Gunadhya | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | author |

Works | Brihatkatha |

Date

Guṇāḍhya could have flourished during the reign of a Satvahana king of Pratishthana (modern-day Paithan, Maharashtra). According to D. C. Sircar, he probably flourished between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE. An alternative account, mentioned in the Nepala Mahatmya of the Skanda Purana, states that Gunadhya was born in Mathura, and was a court poet of the king Madana of Ujjain. Sircar calls this tradition less authentic.[4]

Relevance

The earliest reference to Vikramāditya is traced in the lost Brihatkatha. Guṇāḍhya describes the great generosity, undaunted valour and other qualities of Vikramāditya, whose qualities are also mentioned by Satavahana king Hāla or Halavahana, a predecessor of Gautamiputra Satakarni in his Gaha Sattasai; Guṇāḍhya and Hāla lived close to the time of Vikramāditya.[5]

Guṇāḍhya wrote the Brihatkatha in the little-known Prakrit called Paiśācī, the language of common people of the border regions of Northwest India.[6] Daṇḍin asserts the fundamental importance of the Brihatkatha and states that it was written in prose and not in poetic form suggested by the three known Kashmiri rescensions Haracaritacintamani of Jayaratha included.[7]

Brihatkatha must have been a storehouse of tales about heroes and kings and gods and demigods and also about animals and birds. Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari must be a faithful summary of the original which too was in eighteen Books called Lambakas. The earliest version must have been the Bṛhatkathāślokasaṃgraha of Budhasvamin, the complete work of which has not been found.[8]

Guṇāḍhya must have lived a glorious life; he must have been a versatile writer, a master of literary art capable of weaving into his story of romantic adventures all the marvels of myth, magic and fairy tale.[9] The stories forming the Brihatkatha had a divine origin which origin is recounted by Somadeva. Since King Satvahana has been identified with Shalivahana, Guṇāḍhya must have lived around 78 CE.[10] Guṇāḍhya is perhaps the only author of a well-known text who speaks in the first person. His story is told from his point of view, not by an unseen, omnipresent narrator as in the case of Vyasa and Valmiki.[11]

Notes

Citations

- Winternitz 1985, p. 346.

- Das 2005, p. 104.

- Lacôte & Tabard 1923, pp. 22–25.

- Sircar 1969, p. 108.

- Jain 1972, p. 157.

- Kawthekar 1995, p. 20.

- Keith 1993, pp. 266, 268.

- Raja 1962.

- Datta 1988, p. 1506.

- Srinivasachariar 1974, p. 414,417.

- Bhaṭṭa 1994, p. xxiv.

Bibliography

- Bhaṭṭa, Somadeva (1994). Kathasaritasagara. Penguin Books India. p. xxiv. ISBN 978-0-14-024721-3.

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005). A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0.

- Datta, Amaresh (1988). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- Kathasaritasagara. Penguin Books India. 1994. ISBN 978-0-14-024721-3.

- Kawthekar, Prabhakar Narayan (1995). Bilhana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-779-8.

- Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1993). A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1100-3.

- Lacôte, Felix; Tabard, A. M. (translator) (1923). Essay on Gunādhya and the Brhatkathā. Bangalore City: Bangalore Press. (reprint, from the Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, of Tabard's translation of Lacôte 1908: Essai sur Guṇāḍhya et la Bṛhatkathā at the Internet Archive)

- Raja, C. Kunhan (1962). Survey of Sanskrit Literature. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Sircar, D. C. (1969). Ancient Malwa And The Vikramaditya Tradition. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 108. ISBN 978-812150348-8. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- Srinivasachariar, M (1974). History of Classical Sanskrit Literature: Being an Elaborate Account of All Branches of Classical Sanskrit Literature, with Full Epigraphical and Archaeological Notes and References, an Introduction Dealing with Language, Philology, and Chronology, and Index of Authors & Works. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0284-1.

- Winternitz, Moriz (1985). History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.