Grezzo 2

Grezzo 2[lower-alpha 2] is a first-person shooter video game developed by Italian game designer Nicola Piro and released in 2012. The game is a total conversion modification of the 1993 video game Doom and its development began in the early 2000s, with the version called Grezzo 1, when Nicola Piro attended high school.

| Grezzo 2 | |

|---|---|

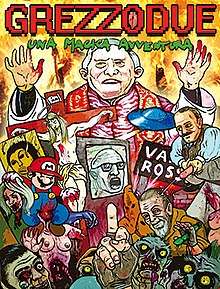

Grezzo 2 cover artwork, featuring caricatures of Pope Benedict XVI and other Italian pop culture icons | |

| Developer(s) | Giochi Penosi[lower-alpha 1] |

| Designer(s) | Nicola Piro |

| Writer(s) | Nicola Piro |

| Engine | Doom Engine |

| Platform(s) | Microsoft Windows |

| Release | 2012 |

| Genre(s) | First-person shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player video game |

The plot follows the adventure of pagan farmer Piro which, annoyed and disgusted by Christianity, plans to kill Jesus Christ to prevent the rise of his religious phenomenon. Gameplay requires the player to face various levels, defeating enemies and bosses and using a wide range of weapons. Many well-known personalities of the culture of Italy appear in the game, as well as references to extremely satirized social, political and religious issues of the country.

Following the 2012 release, Grezzo 2 received significant attention, both inside and outside of its country of origin, due to its extremely blasphemous, vulgar and violent content.

Gameplay

Much like Doom, the gameplay of Grezzo 2 requires the player to navigate to the exit of each level while surviving various hazards on the way. The game contains an exhaustive variety of weapons, many of which are taken from other Doom mods; such weapons include beer bottles, plasma rifles, crucifix launchers, and the "Lanciaratzinger", a powerful cannon which launches digitized sprites of Pope Benedict XVI. Grezzo 2 contains an equally exhaustive amount of NPCs pulled from various games and modifications, such as the innocent bystanders from Carmageddon and the Cabal cultists from Blood.[1] Regardless of their lethality, the player is often required to slaughter through large amounts of NPCs in order to progress. Occasionally, the player fights powerful "boss" enemies representing prominent figures of Christianity, such as Pope John Paul II, Jesus Christ, and God.

Plot

The protagonist of Grezzo 2 is Piro, a pagan farmer from Perugia, Italy. Embittered over the rise of Christianity, Piro embarks on a killing spree, with his first target being the church hosting his grandparents' silver wedding anniversary. Piro massacres the event's reception, and dies shortly thereafter; he then falls into the afterlife to be judged by God, who is depicted as a short-tempered, foul-mouthed man adorned with cultist robes. Depending on the player's actions, Piro can either fight and kill God, or avoid the fight and escape the afterlife.[2]

After returning to Earth and killing countless others, Piro initiates a plan to kill Jesus Christ in his infancy, thereby preventing the creation of Christianity. Piro infiltrates the womb of the Virgin Mary and slays the gestating Jesus within. An egg opportunistically appears where Jesus dies, which Piro fertilizes with his semen. From this egg a new Piro is born, who graphically bursts out of the Virgin Mary, killing her. The reborn Piro pulls out a banjo and plays a song for the Three Wise Men who stood at the Virgin Mary's side.[3]

Development

Grezzo 1, the predecessor of Grezzo 2, was developed by Nicola Piro in the computer room of his high school's religion class. Piro inserted the likenesses of his friends into the game, which was distributed throughout the school. According to Piro, the game was quickly banned at the school once teachers had learned of its content. Because Grezzo 1 contained a large amount of in-jokes that would only be decipherable by his classmates, Piro decided against releasing the game to the public.[2][1] The development of Grezzo 2 took two years, one of which Piro dedicated to researching the editors and assets he'd utilize in making the game. By Piro's admission, much of the content in Grezzo 2 is taken from other games, such as Blood and Carmageddon. Piro would frequently modify the content to suit his own needs, oftentimes by introducing references to Italian pop culture. To this effect, many prominent Italian celebrities and politicians appear in Grezzo 2, typically in the role of antagonists.[2][1]

In discussing his vision for Grezzo 2, Piro explained: "I really wanted to create a game that would piss off any mother, any religious organization, something vulgar and unheard of."[2] In another interview, Piro mused that Grezzo 2 represents how he sees the world: "For me, the world is like this: the Pope is obviously a monster, an enemy, and everything is taken to excess!"[4] Grezzo 2 runs on Skulltag, a modified version of the Doom engine which supports modern operating systems and provides additional amenities for mod creators.

Reception and controversy

As a result of Grezzo 2's graphic violence, sexual content, and irreverence towards religious figures, the game received a significant amount of media attention. Numerous journalists have characterized Grezzo's content as blasphemous.[5][6] Kotaku editor Patricia Hernandez wryly described the content of the mod as "Child murder, priest murder, Barney the dinosaur murder, Mario murder, Buddha murder... really, just murder murder; nothing is sacred."[7] In 2015, the video game live streaming website Twitch added Grezzo 2 to its list of prohibited games, banning users from streaming the title.[8]

Grezzo 2 received an honorary mention during the 2012 Cacowards, with the reviewer labeling the game as "the most psychotic thing to release this year", while praising the over-the-top presentation as "so bad it's awesome".[9]

Legacy

After Grezzo 2, Giochi Penosi developed and released Super Botte & Bamba II Turbo, a 2D fighting game whose roster includes several characters of the Italian trash culture.[10] In March 2018, Giochi Penosi announced the sequel of Grezzo 2, called GrezzoDue 2 (lit. Raw Two 2).[10]

Notes

References

- Luca di Beradino (February 24, 2015). "IL GROTTESCO NEL VIDEOGAME INTERVISTA A NICOLA PIRO". holyeye.com (in Italian). Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Virginia Ricci (April 2, 2013). "Più grezzo del grezzo". vice.com (in Italian). Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Nicola Piro (2012). Grezzo Due: Una Magica Avventura (Windows).

- La Redazione (October 2, 2014). "GREZZO 2: INTERVISTA AGLI SVILUPPATORI". pixelflood.it (in Italian). Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Alessandro Mari (January 8, 2013). "Mod blasfema per Doom". spaziogames.it (in Italian). Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Riccardo Coppola (December 6, 2016). "Cose molto sbagliate nei videgiochi #2: Postal, Playing History 2, Grezzo 2". inmediarex.it (in Italian). Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Patricia Hernandez (January 7, 2013). "How Many Offensive Things Can You Count In This Doom Mod?". kotaku.com. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- "List of Prohibited Games". Twitch. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- "Doomworld -- The 19th Annual Cacowards". doomworld.com. 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Antonio Izzo (March 14, 2018). "Giochi Penosi annuncia GrezzoDue 2, seguito dell'irriverente e satirico Grezzo 2". everyeye.it (in Italian). Retrieved December 26, 2018.