Greenhouse whitefly

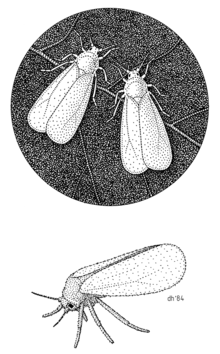

Trialeurodes vaporariorum, commonly known as the glasshouse whitefly or greenhouse whitefly, is an insect that inhabits the world's temperate regions. Like various other whiteflies, it is a primary insect pest of many fruit, vegetable and ornamental crops. It is frequently found in glasshouses (greenhouses), polytunnels, and other protected horticultural environments. Adults are 1–2 mm in length, with yellowish bodies and four wax-coated wings held near parallel to the leaf surface.[1]

| Greenhouse whitefly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Trialeurodes vaporariorum by Des Helmore | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | T. vaporariorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Trialeurodes vaporariorum Westwood, 1856 | |

Life cycle

Females are capable of mating less than 24 hours after emergence and most frequently lay their eggs on the undersides of leaves. Eggs are pale yellow in colour, before turning grey prior to hatching. Newly hatched larvae, often known as crawlers, are the only mobile immature life-stage. During the first and second larval instars, the appearance is that of a pale yellow/translucent, flat scale which can be difficult to distinguish with the naked eye. During the fourth and final immature life-stage referred to as the "pupa", compound eyes and other body tissues become visible as the larvae thicken and rise from the leaf-surface.[1]

Plant damage

All life-stages apart from eggs and "pupae" cause crop damage through direct feeding, inserting their stylet into leaf veins and extracting nourishment from the phloem sap. As a by-product of feeding, honeydew is excreted and that alone can be a second, major source of damage. The third and potentially most harmful characteristic is the ability of adults to transmit several plant viruses. The crop hosts principally affected are vegetables such as cucurbits, potatoes and tomatoes, although a range of other crop and non-crop plants including weed species are susceptible, and can therefore harbour the infection.[2]

Control

Effective control has been provided for many years through the release of beneficial insects, such as the aphelinid parasitoid, Encarsia formosa (Gahan). If required, integrated pest management strategies can incorporate applications of selective chemical insecticides or biopesticides such as Lecanicillium muscarium that complement these natural enemies. For the majority of outdoor crops chemicals are still the most widely used method of control.[2] To study pest resistance management a 787‐Mb high‐quality draft genome has been sequenced and assembled[3].

References

- Ferguson; et al. (July 2003). "Biology Of Whiteflies In Greenhouse Crops". Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- W.S. Cranshaw. "Greenhouse Whitefly". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Xie, Wen; He, Chao; Fei, Zhangjun; Zhang, Youjun. "Chromosome-level genome assembly of the greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum Westwood)". Molecular Ecology Resources. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13159. ISSN 1755-0998.

External links

- USDA Whitefly Knowledgebase