Green-head ant

The green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica), also known as the green ant or metallic pony ant, is a species of ant that is endemic to Australia. It was described by British entomologist Frederick Smith in 1858 as a member of the genus Rhytidoponera in the subfamily Ectatomminae. These ants measure between 5 to 7 mm (0.20 to 0.28 in). The queens and workers look similar, differing only in size, with the males being the smallest. They are well known for their distinctive metallic appearance, which varies from green to purple or even reddish-violet. Among the most widespread of all insects in Australia, green-head ants are found in almost every Australian state, but are absent in Tasmania. They have also been introduced in New Zealand, where several populations have been established.

| Rhytidoponera metallica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Worker from Newcastle, New South Wales | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | R. metallica |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhytidoponera metallica (Smith, 1858) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

This species lives in many habitats, including deserts, forests, woodland and urban areas. They nest underground below logs, stones, twigs, and shrubs, or in decayed wooden stumps, and are sometimes found living in termite mounds. They are among the first insects to be found in burnt-off areas after the embers have stopped smouldering. Rain presents no threat to colonies as long as it is a light shower in continuous sunshine. The green-head ant is diurnal, active throughout the day, preying on arthropods and small insects or collecting sweet substances such as honeydew from sap-sucking insects. They play an important role in seed dispersal, scattering and consuming seeds from a variety of species. Predators include the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) and a number of bird species.

Green-head ant workers are gamergates, meaning they can reproduce with winged males. With workers taking over the reproductive role, queens are relatively insignificant and are rarely produced in colonies. Nuptial flight begins in spring, with males mating with one or two females. Queens that establish their own colonies are semi-claustral, going out and foraging to support their young. Another way colonies are formed is through budding, where a subset of the colony leaves the main colony for an alternative nest site. The green-head ant is known for its painful and venomous sting that can cause anaphylactic shock in sensitive humans. However, they can also be beneficial to humans, acting as a form of pest control by preying on agricultural pests such as beetles, moths and termites.

Taxonomy

The green-head ant was first described in 1858 by British entomologist Frederick Smith in his Catalogue of Hymenopterous Insects in the Collection of the British Museum part VI, under the binomial name Ponera metallica based on two syntypes; a worker and a queen he collected in Adelaide, South Australia.[2] These specimens were later reviewed in 1958 with the designation of a lectotype from the syntypes, but it is unclear which specimen was designated.[3] The material is currently housed in the Natural History Museum in London. In 1862 Austrian entomologist Gustav Mayr moved the species from the genus Ponera and placed it in Rhytidoponera as Ectatomma (Rhytidoponera) metallicum, which at the time was a newly erected subgenus of Ectatomma.[4] Mayr's original reclassification was short-lived as in 1863 he moved the ant from Rhytidoponera to Ectatomma.[5] In 1897 Italian entomologist Carlo Emery named the ant Rhytidoponera metallica and in 1911 designated it as the type species of Chalcoponera, a subgenus of Rhytidoponera;[6][7] the ant was, however, mistakenly identified as the type species of Rhytidoponera by some scientists.[8]

The taxonomy of the green-head ant and other species related to it (forming the R. metallica species group) were a source of confusion due to the high geographic variations in the green-head ant and similar-looking species having been treated as forms (occurrence of multiple morphs). These forms have been described under different names through inadequate characterisations.[9] In 1958 American entomologist William Brown Jr., synonymised Rhytidoponera caeciliae, Rhytidoponera pulchra, Rhytidoponera purpurascens and Rhytidoponera varians with the green-head ant after reviewing the ants in a 1958 journal article.[3] The taxon R. purpurascens was named after its dark-purple appearance by William Morton Wheeler, but R. metallica tends to appear purple around the regions where Wheeler originally collected R. purpurascens. After examining collected specimens, Brown also noted no morphological differences between R. pulchra and R. caeciliae.[3] The species R. varians was described from specimens collected in Darlington, Western Australia. American entomologist Walter Cecil Crawley stated that the subspecies differs from R. metallica by its smaller size and faded metallic colour, varying from yellow-brown in most specimens to a metallic green on the head, thorax and gaster with no evidence of purple colouring.[10] An examination of R. varians showed that the superficial punctures of the gastric dorsum are coarser than usual, but these variants are found not only around the original collection site, but also throughout the southern regions of Australia. Such feature may occur naturally, which disallows R. varians to be considered as a separate population from R. metallica.[3] Under the present classification, the green-head ant is a member of the genus Rhytidoponera in the tribe Ectatommini, subfamily Ectatomminae. It is a member of the family Formicidae, belonging to the order Hymenoptera,[11] an order of insects containing ants, bees, and wasps. Other than its name "green-head ant", it is commonly known as the "metallic pony ant" or "green ant" in Queensland.[12][13] However, this may be confusing, as residents living in northern Queensland call the green-tree ant (Oecophylla smaragdina) "green ants".[13]

Description

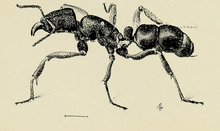

In general, green-head ants are monomorphic (occurs in a single form), measuring 5 to 7 mm (0.20 to 0.28 in) in length and varying in colour, ranging from green-blue to green-purple.[13][14] Their exoskeletons are hard and heavily armoured with a single-segmented waist.[13]

The queens measure 7.4 mm (0.29 in) with the head, thorax, and abdomen exhibiting various metallic colours.[2] The head is usually green behind the eyes and ferruginous (rust in colour) at the front with a less obvious purple tint between the colours. The antennae are ferruginous and the eyes are ovate (shape resembling an egg). The head is emarginate (having a notched tip or edge) from its posterior view and also rugose, along with the thorax and node (a segment between the mesosoma and gaster); these body parts are covered with large confluent punctures.[2] The basal segment of the abdomen has transversely curved striae (grooves which run across the body). The colour of the thorax is usually greenish, the wings are subhyaline (they have a glassy appearance), and the nervures (the veins of the wings) are testaceous (brick-red colour). The legs and apex are ferruginous, and the abdomen is purple.[2]

The workers and queens closely resemble each other, making the two castes hard to distinguish, but the workers differ in having a compressed and elongated thorax, and an abdomen that is predominately green-tinted.[2] The workers are also slightly smaller than the queens, measuring 6 mm (0.24 in).[15] The males are smaller than the workers and queens, measuring 5.5 mm (0.22 in) and appear to be black and fuscous (dark and sombre). The tarsus is fuscous, and the mandibles are rugose.[16] In contrast to the workers and queens, the funicular joints are shorter, the sculpture is denser on the head and thorax, the number of punctures is less than that of the other castes and the postpetiole is coarser. The first segment of the gaster is transversely roughened, and the pilosity (hair) on the legs is less dense.[17] The genitalia of the male is consistent with other formicids, composed of an outer, middle, and inner pair of valves.[18]

The predominant metallic colour is green, but can vary by region, ranging from metallic green to purple.[3] In the Flinders Ranges of South Australia and Alice Springs, the colour of the ants shifts from the typical green to a dark purple colour. In areas with more rainfall such as the New South Wales tablelands and Victorian savannahs, green-head ants are mostly green with purplish tints seen on the sides of the mesosoma.[3] In the northern regions of New South Wales and Queensland, the alitrunk is reddish-violet, which shades into golden around the lower portions of the pleura. The green colour is either limited or completely absent in this case. Most populations have a bright green gaster, except for those living in the central desert. In some areas examined near Brisbane, two different colour forms were discovered within a single colony. One possibility is that the two colour forms may represent two sibling species, but this cannot be confirmed because of lack of evidence.[3] In far north Queensland, populations appear to be dull green and distinct to those living in the south, but it is unknown how the ants in the far north and south hook up at the western and southern regions of the Atherton Tableland. With this said, it is unknown if the far north populations are actually a different species. In addition to colour variation, there are morphological differences among populations. For example, the size and shape of the head and petiole, the length of the appendages, and other sculptural details of the body may all vary.[3]

Sub-mature larvae measure 4.4 mm (0.17 in) and appear similar to sub-mature R. cristata larvae.[19] They can be distinguished by a less-swollen abdomen and shorter body hairs, measuring 0.096 to 0.15 mm (0.0038 to 0.0059 in). On the thorax and abdomen somite, they measure 0.2 mm (0.0079 in). On the flagelliform and ventral portion of the abdominal somites, they measure 0.075 to 0.15 mm (0.0030 to 0.0059 in). The hairs on the head have short denticles, and the antennae have three apical sensilla, each containing a somewhat bulky spinule.[19] Young larvae are much smaller than sub-mature larvae at 1.5 mm (0.059 in) long. They appear similar to sub-mature larvae, but the diameter differs, gradually decreasing from the fifth somite to the anterior end. The hairs measure 0.02 to 0.18 mm (0.00079 to 0.00709 in), with the longest found on the flagelliform and on all somites; the hairs on the somites, however, become sparse. The tips of the hairs on the head are simple or frayed, and overall the hairs measure 0.02 to 0.076 mm (0.00079 to 0.00299 in).[19] Both antennae have a subcone and three apical sensilla that resemble a spinule. The mandibles are sub-triangular with a curved apex. The apical and subapical teeth are sharp and short, but the proximal tooth is blunt. Unlike the mature larvae, the proximal tooth is not divided into two portions.[19]

Distribution and habitat

The green-head ant is among the most widespread of all insects endemic to Australia.[20] The ant is found throughout Victoria, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia.[21] It can be found in most areas of Western Australia but is less common in the north, and is present in the lower regions of the Northern Territory and east of Queensland. They are not present in Tasmania.[21] The green-head ant is an introduced species to New Zealand and was first seen in 1959.[22] Populations of the ant were probably introduced into the country on cargoes of timber; a number of other Rhytidoponera species were most likely introduced the same way.[20] Populations have been established in Napier, as the ants were collected in the town between 2001 and 2003. Nests were previously found in the suburb of Penrose in Auckland and Mount Maunganui, but no specimens have been collected there since the 1960s.[23]

The habitat of the green-head ant varies, ranging from desert, heath, open forests, urban areas and woodland.[14][21] These ants mainly live in moderate wooded or open areas, but they are abundant in lawns and gardens in cities.[20] Nests have been found in dry and wet sclerophyll woodland, mallee, savannah woodland, on roadsides, and in native vegetation.[3][24] Green-head ants are mostly found at altitudes of between 5 and 1,000 m (16 and 3,281 ft) above sea level.[24] The workers construct small and loosely integrated nests underground or in decaying wooden stumps. They may also nest in the termite mounds of Amitermes laurensis.[25] These nests are commonly found beneath grass roots or under logs, stones, twigs, or at the base of shrubs.[14][20][26] Green-head ants can nest in disturbed areas, and, as a result, colonies of these ants are rather common in urban areas. They are among the first insects to be seen foraging for food in areas where bushfires have occurred, and in some cases they return right after the embers have stopped smouldering. Rain also presents no threat to green-head ants as long as it is a light shower in continuous sunshine.[14]

Behaviour and ecology

Colonies show variation as to favoured nest location, with some, for example, avoiding nesting under small rocks and preferring larger ones, which apparently promote colony growth.[27] The promotion of colony growth is associated with territory size, border disputes, the increase of alates (fertile females and males), colony survival, and stable worker production. Colony growth under smaller rocks is slow and restricted. A colony that increases in size requires a larger space to accommodate such growth and the extra brood and workers. Despite this, green-head ants do not discriminate among rocks according to their thickness or temperature. Instead, they choose a rock based on its ground cover dimensions.[27] The distance of a rock is also important; colonies move no more than 3 metres (9.8 ft) to a rock they prefer. This suggests that the cost of moving to a suitable nesting site outweighs the benefits of moving to a larger rock. A large expenditure of energy is required for a move: scouts must first find a suitable site, brood must be transported safely, and the colony is exposed to an increased risk of predation. Nest abandonment by the green-head ant varies, but peaks during summer. Like other temperate species, activity in colonies is greatly reduced during the colder months, which may be the reason there is a high proportion of nest abandonment during summer. Nests abandoned by green-head ants are unlikely to be invaded by other species, so nest invasions are an unlikely cause of nest vacation. The structural breakdown of a nest and competition with other neighbouring colonies is also unlikely, but a possible factor is the seasonal production of food sources and food competition.[27]

Foraging, diet and predators

The green-head ant is a diurnal species that is active throughout the day, quickly foraging on either the ground or vegetation. They are scavengers, predators and seed-eaters, generally having a broad diet of animal material, insects, small arthropods, honeydew from sap-sucking insects and seeds. The workers usually prey on beetles, moths and termites, using their stingers to kill them by injecting venom.[13][14][20][28] The removal of the capitula (structure similar to an elaiosome) from Eurycnema goliath eggs reduces the chances of them being collected by green-head ants that carry them back into their nests.[29] In areas where the meat ant (Iridomyrmex purpureus) is dominant, the green-head ant is not affected by its presence and is still successful in finding food sources.[30] As green-head ants are primitive general predators, in contrast to the more advanced species (which forage in groups and always communicate via trail pheromones), they are unable to defend food sources from dominant ants. They rely heavily on any food source, and the impossibility of successfully defending it from other ants may have led to their peaceful coexistence with dominant species, including meat ants.[30]

Experiments suggest that the specific diets can result in differentiated mortality rates among colonies. In one experiment, three captive colonies were given three different diets: one colony was given the "Bhatkar and Whitcomb diet", an artificial diet consisting of whole raw eggs, honey and vitamin-mineral capsules, another was given honey-water and Drosophila flies while the third colony was given a standardised artificial diet of digestible carbohydrates. The two colonies that were given the standardised artificial diet and honey-water and flies were shown to raise more brood with a lower mortality in workers in contrast to the colony that received the Bhatkar and Whitcomb diet.[31]

The green-head ant is a seed-eating species, showing a preference for seeds with low mechanical defence properties, with stronger seeds being rarely eaten.[32][33] They are known to collect non-arillate seeds and disperse the seeds of the myrtle wattle (Acacia myrtifolia), golden wattle (Acacia pycnantha), coastal wattle (Acacia sophorae), sweet wattle (Acacia suaveolens) and juniper wattle (Acacia ulicifolia).[34] Green-head ants relocate almost half of the seeds they feed on approximately 60 to 78 centimetres (24 to 31 in) away from their nests in both unburned and burned habitats.[35] In some cases, the seeds of Adriana quadripartita are dispersed much farther; the green-head ant accounts for 93% of all ants that collect these seeds and can disperse them as far as 1.5 metres (59 in).[36] One study shows that the green-head ant, along with Aphaenogaster longiceps, removed the highest number of seeds and discarded them on top of their nest, with a few remaining several centimetres under the nest.[37] Most seeds dispersed by the green-head ant and A. longiceps are eventually eaten by Pheidole ants. Since the seeds have a higher survival rate if they are not collected by Pheidole, these two ants are more beneficial to the seeds than Pheidole.[37] Seeds in green-head ant nests rarely germinate.[38]

Foraging factors such as time spent outside and distance travelled by workers has been correlated to colony size.[39] Workers living in smaller colonies tend to forage smaller distances and spend less time outside, whereas those in larger colonies spend more time outside and at greater distances from their nest. Such results have also been seen in the western honey bee (Apis mellifera), but, unlike the honey bees, workers from small and large colonies transported equal workloads. The decreased foraging time may reduce the risk of predation and save energy; for example, the limited energy in R. aurata is a result of time spent looking for food sources, rather than the collection of food items.[39] The shorter foraging periods seen in smaller colonies results in these nests preserving energy and adopting behaviour that is less energetic. Group retrieval only occurs if a worker encounters another nestmate that is heavily loaded with resources. As these ants are solitary foragers and rarely recruit other nestmates, the chance of a worker encountering others is improved by marking the ground with trail pheromones. This behaviour may serve as a simple method of localised chemical recruitment of other nestmates.[39] Marking behaviour increases when workers encounter large prey items, which suggests that foragers with heavy loads deliberately try to raise the encounter rate with nestmates. However, when workers are transporting small to large crickets, marking behaviour decreases to ensure transport efficiency and lower the retrieval time for other ants.[39] Workers can quickly readjust their foraging activity in accordance with food quality.[40]

Large green-head ant colonies exhibit age caste polyethism, where the younger workers act as nurses and tend to the brood and the older workers go out and forage.[41][42] In smaller colonies, age caste polyethism does not occur, with nursing and foraging initiated by both younger and older workers. These results show that ageing is not the mechanism that drives labour among colonies. The emergence of age polyethism in larger colonies is a result of worker specialisation. Workers in small colonies usually tend to the brood much more than those in larger colonies, but this is due to the differentiated social environment between small and large societies.[41] In contrast, old workers from large colonies forage for significant periods of time, and those in small colonies forage less. A predatory species such as the green-head ant may not be able to increase prey retrieval within its environment, even if there is a larger foraging force. This means that the workers may have to spend more time foraging to retrieve any prey item. Contact among nestmates also differs between small and large colonies, strongly suggesting that colony size regulates contact rates. Higher contact rates allow colonies to scan their environment and determine their needs more quickly, which makes a colony react faster. Task allocation patterns (referring to the way that tasks are chosen) are different in small and large colonies, which may determine the contact rate.[41]

Green-head ants are prey for a number of predators, including assassin bugs and the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), in the faeces of which have been found worker ants.[43][44] Birds also eat these ants, including the Australian white ibis (Threskiornis moluccus), black kite (Milvus migrans), masked lapwing (Vanellus miles) and the Australian owlet-nightjar (Aegotheles cristatus).[45] Workers and larvae can be infected by parasites; examined workers were seen with late-stage pupae of an unidentified parasite in their thoraces.[46] In some nests of the green-head ant, some myrmecophilous insects such as the beetle Chlamydopsis longipes are sometimes seen living inside colonies.[47][48]

Life cycle and reproduction

Green-head ant males are produced irregularly throughout the year and are low-flying ants.[49] Recorded nuptial flights begin between September to November at temperatures of 20–25 °C (68–77 °F), when a number of males begin to emerge from their nest.[50] Sometimes, however, the males may return to their nest after briefly appearing outside. The green-head ant is a gamergate species, which means that males can successfully mate with the workers.[51] These workers remain outside their nest with their head and thorax appressed and gaster elevated into the air. Observation has shown the workers first attacking the males when the two first encounter each other, followed by the male mounting the worker by grasping it in the cervical region with its mandibles, successfully attaching itself.[50] Both ants usually rest when they mate, but sometimes the workers may groom themselves or move about several moments after, thereby disengaging with the male. On a few occasions, workers have been seen to move as soon as copulation begins and drag the male, eventually dislodging it. Copulation usually occurs at 8 to 9 in the morning, with pairs lasting for 30 seconds to almost one minute. Most pairs mate once, but others may copulate with each other twice. In some cases, males will successfully mate with two workers, and some pairs may return to their nest while mating.[50]

The green-head ant is known for its rarity of virgin queens, with some nests occasionally producing winged females; queens are able to establish their own colonies in captivity, but out in the wild they have never been seen to establish a colony, suggesting that the species is losing its queen caste.[52] The majority of observations show males mating with workers, but not queens.[50] One factor further suggesting the loss of the queen caste is that the green-head ant is going through an evolutionary process where queens are a rare morphological form with little significance, so workers usually replace the queens and take on the reproductive role.[50][53] Queens still undertake the role of nuptial flight as some have been seen mating with males. They are known to release a sex pheromone from the pygidial gland, an exocrine gland found between the last two abdominal segments.[54][55][56] The ergatoid (wingless reproductive females) queens emerge from their nest and, like the workers, appress their head onto the ground and elevate their gaster, from which the intersegmental membrane at the back of the abdomen extends. The queens then release the sex pheromones, which attracts the males, who frantically search for the queens through agitated locomotion. The males may attempt to copulate with workers that did not "call" for them, suggesting that workers might be able to release these pheromones. When a male makes contact with a queen, the male touches her with his antennae and grasps the female's thorax with his mandibles. A queen is ready to mate when she turns her abdomen to the side, where the male will search for the genitalia with his copulatory apparatus (parts of the organ involved with copulation). The pair may copulate for several minutes.[54]

.jpg)

Colony founding is mostly initiated by a fertilised worker that establishes herself in a closed cell, from which she sometimes emerges to forage for food. Observations show that most workers establishing their own colonies follow the typical behaviour of a Ponerine ant, laying eggs and rearing their larvae. However, the brood in captive colonies founded by workers only emerges as males. Such a case would mean that a new colony is probably formed by a number of workers leaving their parent nest, of which a few individuals are fertilised.[50] This process is called budding, also called "satelliting" or "fractionating", where a subset of the colony leave the main colony for an alternative nest site.[57] This may not be the case entirely, as some queens can establish their own colonies.[58] Inseminated queens can successfully establish a colony in non-claustral, haplometrotic conditions (as in founded by a single queen that hunts for food to feed her young), but the development of a colony straight after colony founding is very slow, whereas other Rhytidoponera species tend to grow faster.[58][59] There is also a clear sign of division of labour between the queens and workers. Upon the death of a queen, workers may sometimes compete and exhibit sexual calling behaviour,[60] which means that workers are able to reproduce in queenless nests.[61][62] Despite the near-absence of queens, long-range dispersal with winged queens may still be an option.[58] Colonies start small but can rapidly expand to the point they are considered mature.[50]

Genetic patterns suggest that green-head ant workers mate with unrelated males from distant colonies.[63] The relatedness among workers is also very low, and there is a high proportion of gamergate ants. If the gamergates are all unrelated, the number of gamergates living in a nest can reach as many as nine; all of these gamergates contribute to the reproduction of young. The average number of gamergates can still be very high if they are related and get a larger share in reproduction. Most of the time, however, gamergates are generally unrelated, and it is uncommon for them to have a degree of relatedness. In many colonies, workers and gamergates police young females, which prevents them from reproducing.[63]

Relationship with humans

The green-head ant possesses a highly potent sting that can be painful but is short-lived.[13][20] An icepack or commercially available spray can be used to relieve the pain, but individuals experiencing an allergic reaction are normally taken to the hospital for treatment.[14] The venom is powerful enough to cause anaphylactic shock in sensitive humans. In a 2011 Australian ant allergy venom study, of which the objective was to determine what native Australian ants were associated with ant sting anaphylaxis, it was shown that 34 participants reacted to the venom of the green-head ant. The rest of the participants reacted to Myrmecia venom, in particular, 176 to M. pilosula alone. The study concluded that four main groups of Australian ants were responsible for causing anaphylaxis. The green-head ant was the only ant that was not a Myrmecia species to cause allergic reactions in participating individuals.[64] Green-head ants have been reported causing mortality amongst poultry.[65] Despite its potential danger to sensitive humans, green-head ants can be beneficial. They can serve as a form of pest control by killing agricultural pests such as beetle and moth larvae and termites.[28]

References

- Johnson, Norman F. (19 December 2007). "Rhytidoponera metallica (Smith)". Hymenoptera Name Server version 1.5. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Smith, F. (1858). Catalogue of Hymenopterous Insects in the Collection of the British Museum part VI (PDF). London: British Museum. p. 94.

- Brown, W.L. Jr. (1958). "Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. II. Tribe Ectatommini (Hymenoptera)" (PDF). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 118 (5): 175–362. doi:10.5281/zenodo.26958.

- Mayr, G. (1862). "Myrmecologische studien" (PDF). Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 12: 649–776. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25912.

- Mayr, G. (1863). "Formicidarum index synonymicus" (PDF). Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 13: 385–460. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25913.

- Emery, C. (1897). "Viaggio di Lamberto Loria nella Papuasia orientale. XVIII. Formiche raccolte nella Nuova Guinea dal Dott. Lamberto Loria". Annali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale Giacomo Doria (Genova). 2. 18 (38): 546–594. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25475.

- Emery, C. (1911). "Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Ponerinae" (PDF). Genera Insectorum. 118: 1–125.

- Wheeler, W.M. (1911). "A list of the type species of the genera and subgenera of Formicidae" (PDF). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 21: 157–175. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25141.

- Brown, W.L. Jr. (1954). "Systematic and other notes on some of the smaller species of the genus Rhytidoponera Mayr". Breviora. 33: 1–11. doi:10.5281/zenodo.26929.

- Crawley, W.C. (1922). "New ants from Australia" (PDF). Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 9 (9): 427–448. doi:10.5281/zenodo.26712.

- Bolton, B. (2014). "Rhytidoponera metallica". AntCat. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Andersen, A.N. (2002). "Common names for Australian ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Australian Journal of Entomology. 41 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6055.2002.00312.x.

- "Green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica)". Sciencentre (Queensland Museum). Government of Queensland. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Australian Museum. "Animal Species: Green-head ant". Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Rhytidoponera metallica (Smith, 1858): Green-head Ant". Atlas of Living Australia. Government of Australia. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Mayr, G. (1866). "Diagnosen neuer und wenig gekannter Formiciden". Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 16: 885–908. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25847.

- Crawley, W.C. (1925). "New ants from Australia - II" (PDF). Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 16 (9): 577–598. doi:10.1080/00222932508633350.

- Forbes, J.; Hagopian, M. (1965). "The male genitalia and terminal segments of the Ponerine ant Rhytidoponera metallica F. Smith (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 73 (4): 190–194. JSTOR 25005974.

- Wheeler, G.C.; Wheeler, J. (1964). "The ant larvae of the subfamily Ponerinae: supplement". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 57: 443–462. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25079.

- Taylor, R.W. (1961). "Notes and new records of exotic ants introduced into New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Entomologist. 2 (6): 28–37. doi:10.1080/00779962.1961.9722798. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016.

- Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (2008). "Species Rhytidoponera metallica (Smith, 1858)". Australian Biological Resources Study: Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra: Government of Australia. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Don, W. (2007). Ants of New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-877372-47-6.

- Don, W.; Harris, R. "Rhytidoponera metallica (Fr. Smith 1858)". Landcare Research New Zealand. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Species: Rhytidoponera metallica". AntWeb. The California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Higashi, S.; Ito, F. (1989). "Defense of termitaria by termitophilous ants". Oecologia. 80 (2): 145–147. Bibcode:1989Oecol..80..145H. doi:10.1007/BF00380142. JSTOR 4219024. PMID 28313098.

- Lowne, B.T. (1865). "Contributions to the natural history of Australian ants" (PDF). The Entomologist. 2: 275–280. doi:10.5281/zenodo.25931.

- Thomas, M.L. (2002). "Nest site selection and longevity in the ponerine ant Rhytidoponera metallica (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)". Insectes Sociaux. 49 (2): 147–152. doi:10.1007/s00040-002-8294-y.

- Fell, H.B. (1940). "Economic importance of the Australian ant, Chalcoponera metallica". Nature. 145 (3679): 707. Bibcode:1940Natur.145..707F. doi:10.1038/145707a0.

- Stanton, A.O.; Dias, D.A.; O'Hanlon, J.C. (2015). "Egg dispersal in the Phasmatodea: convergence in chemical signaling strategies between plants and animals?". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 41 (8): 689–695. doi:10.1007/s10886-015-0604-8. PMID 26245262.

- Gibb, H. (2005). "The effect of a dominant ant, Iridomyrmex purpureus, on resource use by ant assemblages depends on microhabitat and resource type". Austral Ecology. 30 (8): 856–867. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2005.01528.x.

- Dussutour, A.; Simpson, S. J. (2008). "Description of a simple synthetic diet for studying nutritional responses in ants". Insectes Sociaux. 55 (3): 329–333. doi:10.1007/s00040-008-1008-3.

- Meeson, N.; Robertson, A.I.; Jansen, A. (2002). "The effects of flooding and livestock on post-dispersal seed predation in river red gum habitats". Journal of Applied Ecology. 39 (2): 247–258. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00706.x.

- Rodgerson, L. (1998). "Mechanical defense in seeds adapted for ant dispersal". Ecology. 79 (5): 1669–1677. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1669:MDISAF]2.0.CO;2.

- Murray, D.R. (1986). Seed Dispersal. Sydney: Academic Press. pp. 99–100, 110. ISBN 978-0-323-13988-5.

- Beaumont, K.P.; Mackay, D.A.; Whalen, M.A. (2013). "Multiphase myrmecochory: the roles of different ant species and effects of fire". Oecologia. 172 (3): 791–803. Bibcode:2013Oecol.172..791B. doi:10.1007/s00442-012-2534-2. PMID 23386041.

- Beaumont, K.P.; Mackay, D.A.; Whalen, M.A. (2009). "Combining distances of ballistic and myrmecochorous seed dispersal in Adriana quadripartita (Euphorbiaceae)". Acta Oecologica. 35 (3): 429–436. Bibcode:2009AcO....35..429B. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2009.01.005.

- Hughes, L.; Westoby, M. (1992). "Fate of seeds adapted for dispersal by ants in Australian sclerophyll vegetation". Ecology. 73 (4): 1285–1299. doi:10.2307/1940676. JSTOR 1940676.

- Drake, W.E. (1981). "Ant-seed interaction in dry sclerophyll forest on North Stradbroke Island, Queensland". Australian Journal of Botany. 29 (3): 293–309. doi:10.1071/BT9810293.

- Thomas, M. L.; Framenau, V. W. (2005). "Foraging decisions of individual workers vary with colony size in the greenhead ant Rhytidoponera metallica (Formicidae, Ectatomminae)". Insectes Sociaux. 52 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1007/s00040-004-0768-7.

- Dussutour, A.; Nicolis, S.C. (2013). "Flexibility in collective decision-making by ant colonies: Tracking food across space and time". Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 50: 32–38. Bibcode:2013CSF....50...32D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.439.4804. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2013.02.004.

- Thomas, M.L.; Elgar, M.A. (2003). "Colony size affects division of labour in the ponerine ant Rhytidoponera metallica". Naturwissenschaften. 90 (2): 88–92. Bibcode:2003NW.....90...88T. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0396-x. PMID 12590305.

- Giraldo, Y.M.; Traniello, J.F.A. (2014). "Worker senescence and the sociobiology of aging in ants". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 68 (12): 1901–1919. doi:10.1007/s00265-014-1826-4. PMC 4266468. PMID 25530660.

- Griffiths, M.; Kerkut, G.A. (2015). Echidnas: International Series of Monographs in Pure and Applied Biology: Zoology. Canberra: Elsevier. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-4831-5040-6.

- "Robbers and Assassins of the Insect World". The Sydney Mail. Sydney, N.S.W.: National Library of Australia. 6 October 1937. p. 54.

- Barker, R.; Vestjens, W. (1989). Food of Australian Birds 1. Non-passerines. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 108, 151, 239, 423. ISBN 978-0-643-10296-5.

- Whelden, R.M. (1960). "The anatomy of Rhytidoponera metallica F. Smith (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 53 (6): 793–808. doi:10.1093/aesa/53.6.793.

- Oke, C. (1923). "Notes on the Victorian Chlamydospini (Coleoptera), with descriptions of new species". The Victorian Naturalist. 40 (8): 152–162.

- Clark, J. (1928). "Excursion through Western District of Victoria. Entomological Reports. Formicidae" (PDF). The Victorian Naturalist. 45: 39–44.

- Haskins, C.P. (1978). "Sexual calling behavior in highly primitive ants". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 85 (4): 407–415. doi:10.1155/1978/82071.

- Haskins, C.P.; Whelden, R.M. (1965). "Queenlessness, worker sibship, and colony versus population structure in the Formicid genus Rhytidoponera". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 72 (1): 87–112. doi:10.1155/1965/40465.

- Peeters, C. (1991). "The occurrence of sexual reproduction among ant workers". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 44 (2): 141–152. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00612.x.

- Monnin, T.; Peeters, C. (2008). "How many gamergates is an ant queen worth?". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (2): 109–116. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..109M. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0297-0. PMID 17721700.

- Chapuisat, M.; Painter, J. N.; Crozier, R. H. (2000). "Microsatellite markers for Rhytidoponera metallica and other ponerine ants" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 9 (12): 2218–2220. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2000.105334.x. PMID 11123662.

- Hölldobler, B.; Haskins, C.P. (1977). "Sexual calling behavior in primitive ants". Science. 195 (4280): 793–794. Bibcode:1977Sci...195..793H. doi:10.1126/science.836590. JSTOR 1743987. PMID 836590.

- Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 152.

- Meinwald, J.; Wiemer, D. F.; Hölldobler, B. (1983). "Pygidial gland secretions of the ponerine ant Rhytidoponera metallica". Naturwissenschaften. 70 (1): 46–47. Bibcode:1983NW.....70...46M. doi:10.1007/BF00365963.

- Haskins, C.P.; Haskins, E. F. (1979). "Worker compatibilities within and between populations of Rhytidoponera metallica". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 86 (4): 299–312. doi:10.1155/1979/12031.

- Ward, P.S. (1986). "Functional queens in the Australian Greenhead ant, Rhytidoponera metallica: (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 93 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1155/1986/89482.

- Hou, C.; Kaspari, M.; Vander Zanden, H. B.; Gillooly, J. F. (2010). "Energetic basis of colonial living in social insects". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (8): 3634–3638. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.3634H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908071107. PMC 2840457. PMID 20133582.

- Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 222.

- Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 190.

- Trager, J.C. (1988). Advances in Myrmecology (1st ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-916846-38-1.

- Chapuisat, M.; Crozier, R. (2001). "Low relatedness among cooperatively breeding workers of the greenhead ant Rhytidoponera metallica". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 14 (4): 564–573. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00310.x.

- Brown, S.G.A.; van Eeden, P.; Wiese, M.D.; Mullins, R.J.; Solley, G.O.; Puy, R.; Taylor, R.W.; Heddle, R.J. (2011). "Causes of ant sting anaphylaxis in Australia: the Australian Ant Venom Allergy Study". The Medical Journal of Australia. 195 (2): 69–73. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03209.x. PMID 21770873.

- "Poultry Notes". The Daily Advertiser. Wagga Wagga, N.S.W.: National Library of Australia. 13 July 1940. p. 3.

Cited literature

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. (1990). The Ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04075-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links