Film grain

Film grain or granularity is the random optical texture of processed photographic film due to the presence of small particles of a metallic silver, or dye clouds, developed from silver halide that have received enough photons. While film grain is a function of such particles (or dye clouds) it is not the same thing as such. It is an optical effect, the magnitude of which (amount of grain) depends on both the film stock and the definition at which it is observed. It can be objectionably noticeable in an over-enlarged film photograph.

RMS granularity

Granularity, or RMS granularity, is a numerical quantification of film-grain noise, equal to the root-mean-square (rms) fluctuations in optical density,[1] measured with a microdensitometer with a 0.048 mm (48-micrometre) diameter circular aperture, on a film area that has been exposed and normally developed to a mean density of 1.0 D (that is, it transmits 10% of light incident on it).[2]

Granularity is sometimes quoted as "diffuse RMS granularity times 1000",[3] so that a film with granularity 10 means an rms density fluctuation of 0.010 in the standard aperture area.

When the particles of silver are small, the standard aperture area measures an average of many particles, so the granularity is small. When the particles are large, fewer are averaged in the standard area, so there is a larger random fluctuation, and a higher granularity number.

The standard 0.048 mm aperture size derives from a drill bit used by an employee of Kodak.

Selwyn granularity

Film grain is also sometimes quantified in a way that is relative independent of size of the aperture through which the microdensitometer measures it, using R. Selwyn's observation (known as Selwyn's law) that, for a not too small aperture, the product of RMS granularity and the square root of aperture area tends to be independent of the aperture size. The Selwyn granularity is defined as:

where σ is the RMS granularity and a is the aperture area.[4][5]

Grain effect with film and digital

The images below show an example of extreme film grain:

Rallycross car pictured on Agfa 1000 RS slide

Rallycross car pictured on Agfa 1000 RS slide Detail of the same photo to show the grain better

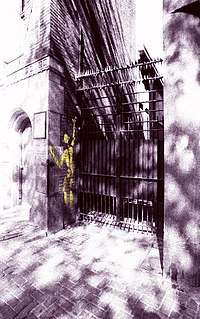

Detail of the same photo to show the grain better Recording Kodak Film 1000 ASA, Amsterdam, Graffiti 1996.

Recording Kodak Film 1000 ASA, Amsterdam, Graffiti 1996.

Digital photography does not exhibit film grain, since there is no film for any grain to exist within. In digital cameras, the closest physical equivalents of film grains are the individual elements of the image sensor (e.g. CCD cell), the pixels; just as small-grain film has better resolution but less sensitivity than large-grain film, so will an image sensor with more elements result in an image with better resolution but less light per pixel. Thus, like film grain, physical pixel size represents the compromise between resolution and sensitivity. However, while film grains are randomly distributed and have size variation, image sensor cells are of same size and are arranged in a grid, so direct comparison of film and digital resolutions is not straightforward. Instead, the ISO setting on a digital camera controls the gain of the electronic amplifier on the readout circuitry of the chip. Ultimately, high ISO settings on a digital camera operating in low light conditions does result in a noisy image, but the visual appearance is somewhat different from traditional photographic film.

The visual and artistic effect of film grain can be simulated in some digital photo manipulation programs by adding grain to a digital image after it is taken. Various raw image processing software packages (such as RawTherapee and DxO PhotoLab) feature "film simulation" effects that apply the characteristics of various film brands, including the graininess. Plugins for the same purpose also exist for various image editors such as Photoshop (e.g. in Nik Collection's Color/Silver Efex).

In digital photography, image noise sometimes appears as a "grain-like" effect.

Film grain overlay

Film grain overlay, sometimes referred to as "FGO", is a process in which film emulsion characteristics are overlaid using different levels of opacity onto a digital file. This process adds film noise characteristics, and in instances with moving images, subtle flicker to the more sterile looking digital medium.

As opposed to computer plug-ins, FGO is typically derived from actual film grain samples taken from film, shot against a gray card.

See also

References

- Brian W. Keelan (2002). Handbook of Image Quality: Characterization and Prediction. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-0770-2.

- Leslie D. Stroebel; John Compton; Ira Current; Richard D. Zakia (2000). Basic Photographic Materials and Processes. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80405-8.

- Efthimia Bilissi; Michael Langford (2007). Langford's Advanced Photography. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-52038-6.

- Hans I. Bjelkhagen (1995). Silver-halide Recording Materials. Springer. ISBN 3-540-58619-9.

- R. E. Jacobson; Sidney Ray; Geoffrey G. Attridge; Norman Axford (2000). The Manual of Photography. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-51574-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Film grain. |

- Film Grain discussed at FLIP Animation blog Retrieved March 2013