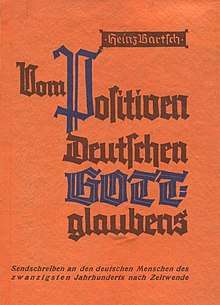

Gottgläubig

In Nazi Germany, Gottgläubig (literally "believing in God"[1][2]) was a Nazi religious term for a form of Non-denominationalism practised by those Germans who had officially left Christian churches but kept their faith in Jesus Christ or a higher power or divine creator. Such people were called Gottgläubige, and the term for the overall movement was Gottgläubigkeit. The term denotes someone who still believes in God, although without having any institutional religious affiliation. The Nazis were not favourable towards religious institutions of their time, but rather sought to revive the golden age of Christianity from centuries prior. They did not tolerate atheism of any type within the NSDAP membership: Gottgläubigkeit was a kind of officially sanctioned unorganised religion equivalent to a “non-denominational Christian” in the United States. The 1943 Philosophical Dictionary defined gottgläubig as: "official designation for those who profess a specific kind of piety and morality, without being bound to a church denomination, whilst however also rejecting irreligion and godlessness."[3] In the 1939 census, 3.5% of the German population identified as gottgläubig.[2]

Origins

In the 1920 National Socialist Programme of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), Adolf Hitler first mentioned the phrase "Positive Christianity". The Party did not wish to tie itself to a particular Christian denomination, but with Christianity in general, and sought freedom of religion for all denominations "so long as they do not endanger its existence or oppose the moral senses of the Germanic race."

When Hitler and the NSDAP got into power in 1933, they sought to assert state control over the churches, on the one hand through the Reichskonkordat with the Roman Catholic Church, and the forced merger of the German Evangelical Church Confederation into the Protestant Reich Church on the other. This policy seems to have gone relatively well until late 1936, when a "gradual worsening of relations" between the Nazi Party and the churches saw the rise of Kirchenaustritt ("leaving the church").[4] Although there was no top-down official directive to revoke church membership, some Nazi Party members started doing so voluntarily and put other members under pressure to follow their example.[4] Those who left the churches were designated as Gottgläubige ("believers in God"), a term officially recognised by the Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick on 26 November 1936. He stressed that the term signified political disassociation from the churches, not an act of religious apostasy.[4] The term "dissident", which some church leavers had used up until them, was associated with being "without belief" (glaubenslos), whilst most of them emphasised they still believed in God and thus required a different word.[4]

The Nazi Party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg was the first to leave his church[5] in November 1933, but for the next three years he would be the only prominent Nazi leader to do so.[4] In early 1936, SS leaders Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich terminated their membership of the Roman Catholic Church, followed by a number of Gauleiter including Martin Mutschmann (Saxony), Carl Röver (Weser-Ems) and Robert Heinrich Wagner (Baden).[4] In late 1936, especially Roman Catholic party members left the church, followed in 1937 by a flood of primarily Protestant party members.[4] Hitler himself never repudiated his membership of the Roman Catholic Church;[6] in 1941, he told his General Gerhard Engel: "I am now as before a Roman Catholic and will always remain so."[7]

Demography

People who identified as gottgläubig could hold a wide range of religious beliefs, including non-clerical Christianity,[4] Germanic neopaganism,[4] a generic non-Christian theism,[9] deism,[2] and pantheism.[2] Strictly speaking, Gottgläubigen were not even required to terminate their church membership, but strongly encouraged to.[10]

By the decree of the Reich Ministry of the Interior of 26 November 1936, this religious descriptor was officially recognised on government records.[8] The census of 17 May 1939 was the first time that German citizens were able to officially register as gottgläubig.[8] Out of 79.4 million Germans, 2.7 million people (3.5%) claimed to be gottgläubig, compared to 94.5% who either belonged to the Protestant or Roman Catholic churches, 300,000 Jews (0.4%), 86,000 adherents of other religions (including Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, neopagans and other religious sects and movements, 0.1%), and 1.2 million (1.5%) who had no faith (glaubenslos).[2][8] Paradoxically, Germans living in urban areas, where support for the Nazi Party was the lowest, were the most likely to identify as gottgläubig, the five highest rates being found in Berlin (10.2%), Hamburg (7.5%), Vienna (6.4%), Düsseldorf (6.0%) and Essen (5.3%).[11]

The term still appeared sporadically a few years after the war, and was recognised in the 1946 census inside the French Occupation Zone, before it faded from official documents.[12]

Himmler and the SS

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, himself a former Roman Catholic, was one of the main promoters of the gottgläubig movement.[2] He was hostile towards Christianity, its values, the churches and their clergy.[2] However, Himmler declared: "As National Socialists, we believe in a Godly worldview."[2] He insisted on the existence of a creator-God, who favoured and guided the Third Reich and the German nation, as he announced to the SS: "We believe in a God Almighty who stands above us; he has created the earth, the Fatherland, and the Volk, and he has sent us the Führer. Any human being who does not believe in God should be considered arrogant, megalomaniacal, and stupid and thus not suited for the SS."[2] He did not allow atheists into the SS, arguing that their "refusal to acknowledge higher powers" would be a "potential source of indiscipline".[13]

Himmler was not particularly concerned by the question how to label this deity; God Almighty, the Ancient One, Destiny, "Waralda", Nature etc. were all acceptable, as long as they referred to some "higher power that had created this world and endowed it with the laws of struggle and selection that guaranteed the continued existence of nature and the natural order of things."[2] According to Himmler, "Only he who opposes belief in a higher power is considered godless"; everyone else was gottgläubig, but should be thus outside of the church. SS members were put under pressure to identify as gottgläubig and revoke their church membership, if necessary under the threat of expulsion.[2]

The SS personnel records show that most of its members who left the church of their upbringing, did so just before or shortly after joining the SS.[2] The Sicherheitsdienst (SD) members were the most willing corps within the SS to withdraw from their Christian denominations and change their religious affiliation to gottgläubig at 90%. Of the SS officers, 74% of those who joined the SS before 1933 did so, while 68% who joined the SS after 1933 would eventually declare themselves gottgläubig. Of the general SS membership, 16% had left their churches by the end of 1937.[14]

See also

References

- Steigmann-Gall, Richard (2003). The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 0-521-82371-4. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- Ziegler, Herbert F. (2014). Nazi Germany's New Aristocracy: The SS Leadership, 1925-1939. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-14-00-86036-4. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "amtliche Bezeichnung für diejenigen, die sich zu einer artgemäßen Frömmigkeit und Sittlichkeit bekennen, ohne konfessionell-kirchlich gebunden zu sein, andererseits aber Religions- und Gottlosigkeit verwerfen". Philosophisches Wörterbuch Kröners Taschenausgabe. Volume 12. 1943. p. 206.. Cited in Cornelia Schmitz-Berning, 2007, p. 281 ff.

- Steigmann-Gall, Richard (2003). The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 9780521823715. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Rosenberg was baptised in the Lutheran St. Nicholas' Church, Tallinn shortly after his birth.

- Christopher Hitchens (22 December 2007). "Hitchens on Hitler". Retrieved 24 January 2018 – via YouTube.

- Toland, John (1992). Adolf Hitler: The Definitive Biography. New York: Anchor Publishing. p. 507. ISBN 978-0385420532.

- Gailus, Manfred; Nolzen, Armin (2011). Zerstrittene "Volksgemeinschaft": Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 195–196. ISBN 9783647300290. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Hans-Adolph Jacobsen, Arthur L. Smith Jr. , The Nazi Party and the German Foreign Office, Routledge, 2012, page 157.

- Steigmann-Gall, p. 221–222.

- Steigmann-Gall, p. 222.

- Albert Zink: Die Pfalz am Rhein. Speyer 1952, Volume D, Table 19 p. 263 f, Konfessionsverteilung im späteren Regierungsbezirks Pfalz bei der Volkszählung vom 26. Januar 1946: in the urban and rural districts, each had three-digit numbers of "Gottgläubigen", together 8,300 of the 931,640 inhabitants (see table 6, p. 259 f for the total) in the Palatinate. Also compare the text from the Heimatjahrbuch Vulkaneifel (fourth last paragraph) on the 1946 census in Jünkerath, French Occupation Zone. Even in 1950, religious statistics with "Gottgläubigen" appear sporadically, for example in Kamen, see auf wiki-de.genealogy.net or in Hameln, in: Erich Keyser, Deutsches Städtebuch, Band Niedersächsisches Städtebuch (Stuttgart 1952), p. 168.

- Burleigh, Michael: The Third Reich: A New History; 2012; pp. 196–197

- State University of New York George C. Browder Professor of History College of Freedonia (16 September 1996). Hitler's Enforcers: The Gestapo and the SS Security Service in the Nazi Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-534451-6. Retrieved 14 March 2013.