Goodman's mouse lemur

Goodman's mouse lemur (Microcebus lehilahytsara) is a species of mouse lemur from the region near Andasibe in eastern Madagascar. The species is named in honor of primatologist Steven M. Goodman. "Lehilahytsara" is a combination of the Malagasy words which mean "good" and "man". The finding was presented August 10, 2005, along with the discovery of the northern giant mouse lemur (Mirza zaza) as a separate species.

| Goodman's mouse lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Cheirogaleidae |

| Genus: | Microcebus |

| Species: | M. lehilahytsara |

| Binomial name | |

| Microcebus lehilahytsara | |

| |

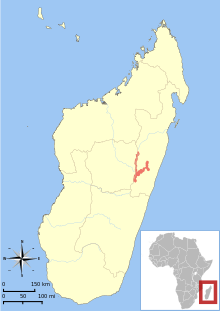

| Distribution of M. lehilahytsara[1] | |

In 2005, Goodman was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship for his discovery and further research in Madagascar.

Description

Mouse lemurs are among the smallest primates, and Goodman's mouse lemur is no exception.[4] Although not the smallest overall, Goodman's mouse lemur has a head-body length comparable to M. berthae which is the smallest known primate.[4] The average size ranges from 45-48 grams, with males being slightly larger than females.[4] Goodman's mouse lemur is mainly maroon with a white underbelly and orange tint on their backs.[4]

Goodman's lemurs undergo daily torpor as well as winter torpor.[5][6] Their tails are able to store fat which is useful in preparing for winter torpor.[4] Although, almost all females experience torpor each winter, not all males go into winter torpor annually.[6] For those males that do enter winter torpor, they exit torpor on average 20 days prior to females.[6] This is likely so males can better prepare for mating which happens almost immediately following the ending of female winter torpor.[6] The males that do not go into winter torpor are often older males that are better able to compete against younger males in procuring a mate; although, they often still undergo daily torpor.[6]

Social behavior

Goodman's mouse lemurs spend most of their waking time alone.[5] They are generally only found in pairs during reproduction and when altercations.[5] Approximately 51% of these altercations involve food.[5] Although females tend to be smaller than males, when fighting over food, females often come out as the winners.[4][5][6] This is because females are more dominant than males in Goodman's mouse lemurs.[5][6] Because females are more dominant, males tend to have a greater foraging area.[5] In some cases, the male's feeding area can be up to four times the size of females feeding area.[5] It has been proposed that the larger area is due to being chased away from better feeding grounds by the dominant females.[5][6]

However, not all social behavior is negative in Goodman's mouse lemur. Oftentimes groups of two to four lemurs of the same sex will gather together to sleep.[5] This is likely to conserve heat.[5] Most often in a group of females, those that share a sleeping space are related, however, groups of males do not show much if any relation with those they sleep with. T[5] In addition to mutualistic sleeping behavior, these lemurs share another positive social interaction. During the mating season, males and females must come together fairly peacefully. This happens in the spring shortly after waking up from winter torpor.[6] The males have large testes, which implies that as opposed to male-male competition in fighting, they are much more likely to undergo sperm competition which limits some of the social aspects of breeding that many other animals undergo.[4] The male Goodman's Mouse Lemur is known to have more bodyweight than the female during the reproductive season. However, other times, how much these species weigh can vary according to the season.[5][7][6]

Phylogeny

The genus Microcebus is shown to have diverged approximately ten to nine million years ago.[8] This split allowed for greater radiation of mouse lemurs. The mouse lemurs split into three distinct clades.[8] Goodman's mouse lemur has been grouped with five other species due to mitochondrial DNA sequencing.[8] 540 thousand years ago M. marohita initially split from the other four mouse lemur populations within that clade.[8] The most recent split was about 52 thousand years ago when M. lehilahytsara and M. mittermeieri became two distinct species.[8]

Correlated with the most recent speciation was a climatic change period.[8] It has been proposed that this climate change likely would have desiccated the central highlands of Eastern Madagascar.[8] The change in climate and habitat is likely the cause of the recent speciation.[8] Evidence for this is that the habitat for Goodman's Lemur does not overlap with any other mouse lemurs.[9] The habitat would have changed in such a way that the lemurs that would become Goodman's mouse lemur would be the only ones that could survive in that habitat. Their diet really varies from insects to fruits, flowers, nectar, gum and leaves. Not only food choices are diverse, but also their metabolism, body temperature and body mass can vary from time to time depending on the season and the conditions of the environment.[10]

References

- Dolch, R., Radespiel, U. & Blanco, M. (2020). "Microcebus lehilahytsara". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T136199A115580879. Retrieved 12 July 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Mittermeier, R.; Ganzhorn, J.; Konstant, W.; Glander, K.; Tattersall, I.; Groves, C.; Rylands, A.; Hapke, A.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Mayor, M.; Louis, E.; Rumpler, Y.; Schwitzer, C. & Rasoloarison, R. (December 2008). "Lemur Diversity in Madagascar" (PDF). International Journal of Primatology. 29 (6): 1607–1656. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9317-y. hdl:10161/6237.

- Kappeler; Rasoloarison; Razafimanantsoa; Walter; Roos (2005). "Morphology, Behaviour and Molecular Evolution of Giant Mouse Lemurs (Mirza spp.) Gray, 1870, with Description of a New Species". Primate Report. 71.

- Jurges; Kitzler; Zingg; Radespiel (2013). "First Insights into the Social Organisation of Goodman's Mouse Lemur (Microcebus lehilahytsara) – Testing Predictions from Socio-Ecological Hypotheses in the Masoala Hall of Zurich Zoo". Folia Primatologica. 84: 32–48. doi:10.1159/000345917.

- Karanewsky; Bauert; Wright (2015). "Effects of Sex and Age on Heterothermy in Goodman's Mouse Lemur (Microcebus lehilahytsara)". International Journal of Primatology. 36 (5): 987–998. doi:10.1007/s10764-015-9867-8.

- Ezran, Karanewsky, Camille, Caitlin. "The Mouse Lemur, a Genetic Model Organism for Primate Biology, Behavior, and Health". Genetics society of America. O. Hobert.

- Toder, AD; Cambell, CR; Blanco; dos Reis; Ganzhorn; Goodman; Hunnicutt; Larsen; Kappeler; Rasoloarison; Ralison; Swofford; Weisrock (2016). "Geogenetic patterns in mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) reveal the ghosts of Madagascar's forests past". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (29): 8049–8056. doi:10.1073/pnas.1601081113. PMC 4961119. PMID 27432945.

- Roos; Kappeler (2006). "Distribution and Conservation Status of Two Newly Described Cheirogaleid Species Mirza zaza and Microcebus lehilahytsara". Primate Conservation. 21: 51–53. doi:10.1896/0898-6207.21.1.51.

- KJ, Gron. "Mouse lemur (Microebus) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology". Primate factsheets. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Goodman's mouse lemur |

- Two new lemur species discovered - Press release from the Chicago Field Museum

- Photos from ARKive.

Arvedlund, M. & Nielsen, L.E. (1996) Do the anemonefish Amphiprion ocellaris (Pisces: Pomacentridae) imprint themselves to their host sea anemone Heteractis magnifica (Anthozoa: Actinidae)? Ethology, 102, 197–211⟨⟩