Gomani II

Inkosi ya Makosi (chief of chiefs) Gomani II was born Zitonga (child of knobkerries) at Chipiri in present-day Mozambique. His mother was naNgondo, junior wife to Gomani I, also known as Chatamthumba.[1]

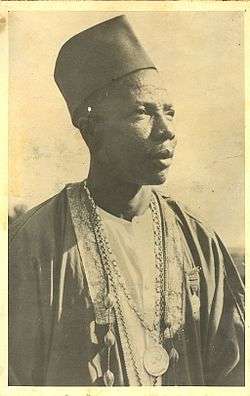

| Gomani II, Zitonga / Philip | |

|---|---|

Zitonga Gomani II, Inkosi ya Makosi of the Gomani Ngoni in Malawi | |

| Reign | 1921-1954 |

| Born | 1921 Chipiri, Mozambique |

| Died | 1954 (aged 32-33) |

| Issue | Gomani III, Willard |

| Father | Gomani I, Chatamthumba |

| Mother | naNgondo |

| Occupation | Chief of chiefs of the Gomani Ngoni Tribe |

Early life

He was a descendant of Mputa and Chikuse, becoming paramount of the Maseko Ngoni of Ntcheu, southern Malawi, from 1921 to 1954. He was also one of the few leaders to have stood against the establishment of Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.[2]

After mastering the basics of reading and writing, Zitonga went to Henry Henderson Institute in Blantyre. He was baptised in 1921, the year he became chief, reviving the Maseko royal house.[3]

Taking office

Under the Native Ordinance of 1933, Zitonga, now using the Christian name of Philip, was officially recognised as the paramount chief of Ntcheu district. Oct 27, 1926, he was guest of honour when people of the central Angoniland had built an obelisk, in memory of his father Gomani 1, who was killed by British colonialists.

In the 1930s, when the colonial government introduced modern agriculture, Gomani II encouraged his people to adopt them, becoming a model chief.[4]

Resistance to Federation, arrest and death

Totally opposed to the Federation of Nyasaland and Rhodesia, he was supposed to be part of the delegation of chiefs to London to oppose its institution. But because of poor health, his son Willard represented him. This delegation met some key figures in London including Reverend Michael Scott at the African Bureau and Cannon Collins of Christian Action.

When the Federation was imposed in 1953, Gomani began to pursue resistance by ignoring official agricultural and conservation regulations. In response, the colonial government suspended and then withdrew its recognition as the paramount chief. In May 1953, the police tried to force Gomani out of the district but failed due to the thousands of people that had gathered at his house in Lizwe la Zulu (or Lizuli in short).[5]

In the midst of the chaos, Gomani and heir to his throne, Willard, together with Reverend Michael Scott, escaped into Mozambique where they hid near Villla Courtinho. Michael Scott was visiting the chief's court when this happened. They were arrested by Mozambican authorities and handed back to the authorities in Malawi. Scott was declared a prohibited immigrant and deported.[6]

His arrest was followed by a major disquiet throughout the colony.

In June 1953, he was due to appear in the magistrate court in Zomba. He could not appear because he was sick, admitted at the Seventh Day Adventist hospital in Thyolo, southern Malawi. He died shortly, and was buried at Lizulu. His funeral was attended by thousands of people including the leading nationalists of the day.

He was succeeded by his son Willard, who became Gomani III.

References

- Phiri, Desmond (1982). From Nguni to Ngoni. Popular Publications. p. 113.

- Karinga, Owen (2001). Historical Dictionary of Malawi. Scarecrow. p. 144.

- Karinga, Owen (2001). Historical Dictionary of Malawi. Scarecrow. p. 144.

- Ross, Andrew (2009). Colonialism to Cabinet Crisis. Kachere. p. 39.

- Power, Joey (2010). Political Culture and Nationalism in Malawi. University of Rochester Press. pp. 67–68.

- Ross, Andrew (2009). Colonialism to Cabinet Crisis. Kachere. p. 74.