Glarentza

Glarentza (Greek: Γλαρέντζα) was a medieval town located near the site of modern Kyllini in Elis, at the westernmost point of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece. Founded in the mid-13th century by William II of Villehardouin, the town served as the main port and mint of the Frankish Principality of Achaea, being located next to the Principality's capital, Andravida. Commerce with Italy brought great prosperity, but the town began to decline in the early 15th century as the Principality itself declined. In 1428, Glarentza was ceded to the Byzantine Despotate of the Morea, and served as its co-capital, being the residence of one of the Palaiologos despots, until the Ottoman conquest in 1460. Under Ottoman rule, Glarentza declined rapidly as the commercial links with Italy were broken, and by the 16th century was abandoned and falling into ruin. Little remains of the town today: traces of the city wall, of a church and a few other buildings, as well as the silted-up harbour.

History

Glarentza was founded in the mid-13th century by William II of Villehardouin (ruled 1246–78), the ruler of the Principality of Achaea,[1] a Frankish state established after the Fourth Crusade and encompassing the Peloponnese or Morea peninsula in southern Greece.[2] Its Frankish foundation is evident in its name, Clarence or Clairence in French, Chiarenza or Clarenza in Italian, Clarentia or Clarencia in Latin, rendered Κλαρέντσα (Klarentsa), Κλαρίντζα (Klarintza), or Γλαρέντζα (Glarentza) in contemporary Greek documents.[3]

The medieval town was located a bit further west of the modern village of Kyllini, on the northern tip of a headland that forms the westernmost point of the Peloponnese. This was a site known since Antiquity as the best anchorage in all of Elis, and was likely the site of the ancient city of Cyllene.[4] Glarentza was established as the haven for the Principality's capital, located inland at Andravida, some 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) away. Along with Andravida and the fortress of Clermont or Chlemoutsi, some 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from the port, Glarentza formed the administrative heart of the Principality of Achaea.[1][5]

Glarentza profited from its location and became the main port for communication and traffic between the Morea and Italy.[4] As described in the town's Greek Ministry of Culture website, Glarentza "rapidly established itself as the most important financial and urban centre of the Crusader principality, with an international renown",[1] while according to the medievalist Antoine Bon, it was "the agglomeration which should most resemble, by its activity, a city in the modern sense of the word".[6] It was a cosmopolitan city, frequented by emissaries from Italy, soldiers and merchants, chiefly Venetians. Trade brought great prosperity, as evidenced by the fact that it used its own system of weights and measures in the 14th century. It featured a hospital as well as banks, lodgings for the mariners, and a Franciscan monastery.[1][7] Based on a 1391 list of fiefs, the town counted ca. 300 hearths, making it among the largest in the Principality.[8]

The town was also the site of the princely mint, which from the 13th century until its cessation, in 1353, struck denier tournois or tornese coins, inscribed initially with [DE] CLARENTIA, and, from the reign of Florent of Hainaut (ruled 1289–97) onwards, with DE CLARENCIA.[1][9] Although Andravida was the main residence of the princely court, Glarentza too was a location of political significance, and several parliaments and assemblies took place there, such as the adjudication on the inheritance of the Barony of Akova in 1276, or the parliament and oath of allegiance to Isabella of Villehardouin and Florent of Hainaut in 1289.[10] Glarentza was surrounded by a set of walls, but scholars have long disputed exactly when this was done. The debate concerns the relation between Glarentza and the nearby fortress of Clermont/Chlemoutsi, which in the view of those who consider Glarentza to have originally been unfortified served as the town's citadel, in which case this was probably the original site of the mint, whence its alternative name of "Castel Tornese".[11]

In June 1315, Glarentza was captured by the Aragonese troops of the infante Ferdinand of Majorca, who claimed the princely title of Achaea for himself by virtue of his marriage to Isabella of Sabran, granddaughter of William II of Villehardouin. Ferdinand made Glarentza his residence, and soon seized all of Elis, aided by the defection of several Achaean barons dissatisfied with the Principality's rule by the Angevins of Naples.[12][13] Ferdinand began minting coins with his name—the rarest issues of the Glarentza mint—but his reign was cut short with the arrival of the legitimate claimants, Matilda of Hainaut and Louis of Burgundy. In the Battle of Manolada, fought to the northeast of Glarentza on 5 July 1316, the Aragonese were defeated and Ferdinand was killed. The remainder of his army fled to Glarentza, and soon handed over the town and the other fortresses they had occupied and departed the Peloponnese, taking the corpse of Ferdinand with them.[14][15]

The town's decline began in the early 15th century, following the worsening fortunes of the Principality itself.[1] At that time, Achaea, under Prince Centurione II Zaccaria (ruled 1404–30), found itself endangered by the attacks of the Byzantines of the Despotate of the Morea on the one hand and the expansionist designs of the Tocco family of Cephalonia and Zakynthos on the other. In late 1407, Centurione's own brother-in-law Leonardo II Tocco seized Glarentza and reaped an enormous booty, as recorded in the Chronicle of the Tocco. It took several years of conflicts and diplomatic manoeuvrings before a Venetian-mediated deal restored the city to Centurione in July 1414.[1][16][17] In 1417, the Byzantines under the Despot Theodore II Palaiologos and his brother John VIII Palaiologos, launched another attack on the remains of the Principality. The brothers made swift progress, forcing Prince Centurione to retire to Glarentza, which was unsuccessfully attacked by the Byzantines. A truce was concluded in 1418, but in the same year, an Italian adventurer, Olivier Franco, seized the town, which in 1421 he sold to Carlo I Tocco, Leonardo's elder brother.[18][19]

With Glarentza in their hands, the Tocchi now began to openly pursue their aspirations in the Peloponnese, and attacked the territories of the Latin Archbishop of Patras Stephen Zaccaria, Centurione's brother.[20] In 1427, the Byzantines, led by emperor John VIII in person, attacked the Tocco lands in the Peloponnese. After the Byzantine fleet defeated his navy, Carlo was forced to submit, and in 1428, Glarentza was handed over as part of the dowry of his niece, Maddalena, who was married to the Despot Constantine Palaiologos (the future last Byzantine emperor).[21][22] When Constantine besieged Patras in 1429, a Catalan fleet that came to the city's aid captured Glarentza, forcing Constantine to ransom it back. He then destroyed its fortifications, so that it could no longer be seized and used by a western power.[1][23]

In 1430, following the final subjugation of the Principality of Achaea by the Byzantines, the Peloponnese was divided into appanages among the various Palaiologos princes. Glarentza became the residence of Thomas Palaiologos until 1432, when he exchanged his portion with Constantine, who had originally settled at Kalavryta.[24] In 1446, Glarentza and its surrounding region were raided by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Murad II, and in 1460, it fell to the Ottomans along with the remainder of the Byzantine Peloponnese.[1] Although nearby Chlemoutsi continued to play a role as a military stronghold until the 19th century—it was garrisoned by the Venetians during the Ottoman–Venetian War of 1463–79, and attacked by the Knights of Malta in 1620[25]—Glarentza itself seems to have rapidly fallen into obscurity under the Ottomans, apparently declining as the maritime links with Italy were severed. By the 16th century, it was already abandoned and half-ruined.[9] The ruins were described by successive travellers until the 19th century, and photographs were also taken later. During the German occupation of Greece in World War II, the German Army demolished many of the remains.[1]

In the early 19th century, several authors and travellers, like Robert Byron, contended that Glarentza (in its Latin form, Clarentia/Clarencia) gave its name to the royal English title of the "Duke of Clarence", via Princess Matilda of Hainaut and her cousin Philippa of Hainaut,[26][27] a claim that has been repeated by reputable publications like the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon encyclopedia into the 20th century.[28] However, this view was conclusively rejected already in 1846 by the military officer and antiquarian William Martin Leake, who pointed out that at no time did English royalty hold Moreote titles, and that "Clarence" originates from Clare, Suffolk, and not Glarentza.[29]

Location and archaeological remains

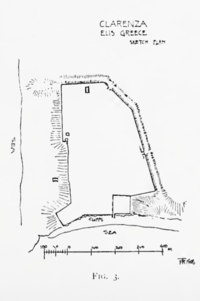

The town of Glarentza was situated on a small plateau, sloping slightly downwards from west to east, at the extreme northwestern end of the peninsula known in Antiquity as Chelonatas. The town occupied an irregular shape of ca. 450 metres (1,480 ft) from east to west and 350 metres (1,150 ft) from north to south, i.e. a surface of ca. 8,800 square metres (95,000 sq ft). The northern and western sides of the town bordered on the sea and were protected by a cliff of some 50 m in height descending to the sea. The port was located in the north, shielded from the dangerous western and southwestern winds.[30]

There are very few material remains of the medieval town today. The city wall that surrounded the settlement has largely disappeared and is difficult to trace today, but from the remains of its foundations it does not appear to have been a substantial fortification. It was lightly built, with a thickness of perhaps 1.8–2 metres (5.9–6.6 ft), reinforced by rectangular towers. The three gates have left far more substantial remains. The eastern, southeastern and southern sides were fronted by a ditch of some 20–22 metres (66–72 ft), with the excavated soil dumped on the inner side and used to elevate the city wall. A small citadel was located in the southwestern corner of the town.[31] The port was separated from the main town by a wall, and was situated in an excavated basin (today a swamp) and probably separated from the sea by an artificial mole and protected by extensions of the city walls. The entrance to the harbour was from the west, offering protection from both the wind and the coast's shoals.[32]

Among the few remains of buildings from the interior of the town, most notable are a large monumental staircase and a large church, with dimensions of some 43 by 15 metres (141 ft × 49 ft), in the northeast. The church was of relatively simple construction, but of unusual size, and A. Bon proposes its identification with the church of the Franciscans, where assemblies of the nobles of Achaea were held in 1276 and 1289. The remaining portions of the church's walls were completely destroyed by the German Army during the Occupation.[33]

The site is currently managed by the 6th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities. It is accessible by car, and is open for visitors.[34]

References

- Ralli, A. Κάστρο Γλαρέντζας: Ιστορικό (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Bon 1969, pp. 59–73.

- Bon 1969, p. 320 (note 3).

- Bon 1969, p. 321.

- Bon 1969, pp. 320, 602.

- Bon 1969, p. 320.

- Bon 1969, pp. 321–322.

- Bon 1969, pp. 691–692.

- Bon 1969, p. 324.

- Bon 1969, pp. 165, 320, 322.

- Bon 1969, pp. 322–324.

- Bon 1969, pp. 191–192.

- Topping 1975, pp. 110–112.

- Bon 1969, pp. 192–193.

- Topping 1975, pp. 112–114.

- Bon 1969, pp. 281–284.

- Topping 1975, pp. 161–162.

- Bon 1969, pp. 285–288.

- Topping 1975, pp. 162–163.

- Bon 1969, pp. 288ff..

- Bon 1969, p. 291.

- Topping 1975, pp. 164–165.

- Bon 1969, p. 292.

- Bon 1969, p. 293.

- Traquair 1907, pp. 276–277.

- Trant 1830, p. 4.

- Stoneman 1994, p. 56.

- "Clarence [3]". Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon (in German). 4. Leipzig. 1906. p. 174.

- Leake 1846, p. 212.

- Bon 1969, pp. 602–603.

- Bon 1969, pp. 602–606.

- Bon 1969, pp. 606–607.

- Bon 1969, pp. 559–566, 607.

- Ralli, A. Κάστρο Γλαρέντζας: Πληροφορίες (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

Sources

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe (in French). Paris: De Boccard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leake, William Martin (1846). Peloponnesiaca: A Supplement to Travels in the Moréa. London: J. Rodwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stoneman, Richard, ed. (1994). A Literary Companion to Travel in Greece. L. Paul Getty Trust. ISBN 0-89236-298-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1311–1364". In Hazard, Harry W. (ed.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 104–140. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1364–1460". In Hazard, Harry W. (ed.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 141–166. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Traquair, Ramsay (1907). "Mediaeval Fortresses in the North-Western Peloponnesus". The Annual of the British School at Athens, No. XIII, Session 1906–1907. London. pp. 268–284.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trant, Thomas Abercromby (1830). Narrative of a journey through Greece in 1830: With remarks upon the actual state of the naval and military power of the Ottoman empire. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- D. Athanasoulis, Γλαρέντζα - Clarence