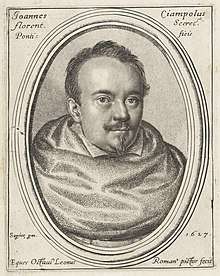

Giovanni Ciampoli

Giovanni Ciampoli or Giovanni Battista Ciampoli (Florence, 1589 – Iesi, 8 September 1643) was a priest, poet and humanist. He was closely associated with Galileo Galilei and his disputes with the Catholic Church.

Education and friendship with Galileo

With modest family origins, he was prepared from an early age for a literary career and had a talent for poetry. He was educated at the Universities of Padua and Pisa, where he met Galileo and became his pupil. Their relationship was renewed at the Medici court, where he was among Galileo’s circle of friends.[1]

His correspondence with Galileo stretched over many years. In February 1615 he wrote to reassure him that the furore about his Copernican opinions had died down, and 'the Friars don't seem to talk or think about that business any more.' [2] In 1619, when Galileo published his Discourse on the Comets, Ciampoli warned him that the Jesuits 'were much offended and were preparing to strike back.'[3]

Church and literary career

In 1614, after completing his studies, Ciampoli moved to Rome where he took holy orders. He was soon introduced to the circles of the Roman Curia and when Galileo was first investigated in 1615-16, out of consideration for his loyalty to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, kept up regular communication with his friend Galileo about developments within the senior ranks of the Catholic Church. Thereafter, in 1618, thanks to the good offices of Galileo, he was inducted into the Accademia dei Lincei together with his friend Virginio Cesarini.[4]

In 1621 he was promoted to Secretary of Briefs to Pope Gregory XV and in 1623 he became chamberlain to Pope Urban VIII, whom he had come to know when, as Maffeo Barberini, he had been Cardinal legate to Bologna. With a lively intellect and an amiable character, he maintained an extensive correspondence with many of the scientists of his time, including Ippolito Aldobrandini, Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, Federigo Borromeo, Giovanni Battista Strozzi the younger, and Evangelista Torricelli.

Galileo controversy

Ciampoli read a draft of Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1630, after which he wrote to Galileo assuring him of the Pope’s favourable view. At the same time, he indicated to the Pope that Galileo had faithfully followed the directions he had given him concerning how the book was to be written. His influence was pivotal in ensuring that the book obtained the necessary authorisation of the Church for publication in 1632. This turned to his disadvantage after the book was published, when Urban VIII decided that both Ciampoli and Galileo had deceived him about the book’s arguments.[5] The Pope also regarded Ciampoli as too sympathetic to radical philosophical ideas espoused by Galileo and others in his circle.[6] The Pope removed Ciampoli from his office in April 1632 and he left Rome in November of that year.[7]

Exile and later years

Before handing over his post as chamberlain to his successor, Monsignor Herrera, Ciampoli had taken care to have two sets of copies made of his diplomatic archives. When he was dismissed he was ordered to leave his copies in his office, but he had already secured the second set of copies, which he took with him together with his large personal archive when he left Rome. This included his books and scientific papers, correspondence with Galileo, and many other works.[8]

Ciampoli was exiled first to the town of Montalto delle Marche, where he served as governor, and later to governorships in Norcia (1636), San Severio della Marca (1637), Fabriano (1640), and Iesi. He maintained contact by letter with many important figures, including Cardinal Mazarin and Prince Maurice of Savoy. He also remained in contact with Valerianus Magnus, theologian and philosopher at the court of Władysław IV Vasa, King of Poland. Through his good offices, Ciampoli was appointed official historiographer to the King.[9]

When he died in 1643, Ciampoli bequeathed not only four volumes on the history of Poland, but all his manuscripts, including both his scientific and his poetic works, to the King of Poland. He intended his collected archive to be transported to Poland, but before the necessary arrangements could be made, representatives of the Holy Office appeared with a sequestration order, seized everything, and took it to Rome. Of his scientific work and his correspondence with Galileo, no further trace remains. Some of his historical and literary works were passed on to the Barberini and Casanatense libraries and to other collections. His poetry and prose writings, together with his History of Poland, were published through the Holy Office,[10] edited by his friend Francesco Sforza Pallavicino.[11]

Works

- Rime, Roma, Corbelletti, 1648 (Poems)

- Poesie Sacre, Bologna, Zenero, 1648 (Sacred Poetry)

- Prose, Bologna, 1649 (Prose)

- Lettere, Firenze, Amador Massi, 1650 (Letters)

- Poesie funebri e morali, Bologna, Ferroni, 1653 (Moral and Funeral Poetry)

- Dai fragmenti, Bologna 1654 (Fragments)

- Rime scelte, Roma, di Falco, 1666 (Selected Rhymes)

- Dialogo sul Sole e il foco (Dialogue concerning the Sun and Fire)

References

- Carmine Jannaco, Martino Capucci, Il Seicento, Piccin, 1986, p. 265

- The Crime of Galileo, Giorgio de Santillana, University of Chicago Press 1955, p.114

- The Crime of Galileo, Giorgio de Santillana, University of Chicago Press 1955, p.154

- Giuseppe Gabrieli, Due prelati Lincei in Roma alla corte di Urbano VIII: Virginio Cesarini e Giovanni Ciampoli, in «Atti dell'Accademia degli Arcadi», Roma, 1929-30

- The Crime of Galileo, Giorgio de Santillana, University of Chicago Press 1955, p.192

- In a letter from Niccolini to Cioli, Urban VIII is quoted as saying "May God help Ciampoli too, when it comes to the new opinions, for he is also a friend of this new philosophy." Cited in Galileo Heretic, Pietro Redondi, Princeton University Press 1987 p.258

- Galileo Heretic, Pietro Redondi, Princeton University Press 1987 p.266

- Galileo Heretic, Pietro Redondi, Princeton University Press 1987 p.267

- Galileo Heretic, Pietro Redondi, Princeton University Press 1987 pp.266-67

- Galileo Heretic, Pietro Redondi, Princeton University Press 1987 pp.266-68

- Giovanni Baffetti, Un problema storiografico: tra Ciampoli e Pallavicino, «Lettere italiane», Anno 2004 - N° 4, Ottobre-dicembre, Pag. 602-617