Gertrud Kolmar

Gertrud Käthe Chodziesner (10 December 1894 – March 1943), known by the literary pseudonym Gertrud Kolmar, was a German lyric poet and writer. She was born in Berlin and died, after her arrest and deportation as a Jew, in Auschwitz, a victim of the Nazi Final Solution. Though she was a cousin of Walter Benjamin, little is known of her life. She is considered one of the finest poets in the German language.[1]

Life

Gertrud Kolmar came from an assimilated middle-class German Jewish family. Her father, Ludwig Chodziesner, was a criminal defense lawyer. Her mother Elise's maiden name was Schoenflies. She grew up in Berlin's Charlottenburg quarter, in the present-day Berlin-Westend, and was educated in several private schools, the last one being a women's agricultural and home economics college at Elbisbach near Leipzig. While active as a kindergarten teacher, she learnt Russian and completed a course in 1915/1916 for language teachers in Berlin, graduating with a diploma in English and French. At about this time she had a brief affair with an army officer, Karl Jodel, which ended with an abortion, which her parents insisted on her having. During the last two years of World War I she was also employed as an interpreter and censor of soldiers' correspondence in a prisoner-of-war camp in Döberitz, near Berlin.

In 1917 her first book, simply titled 'Poems', (Gedichte) appeared, under the pseudonym of Gertrud Kolmar, Kolmar being the German name for the town of Chodzież in the former Prussian province of Posen from which her family came. After the war, she worked as a governess for several families in Berlin, and briefly, in 1927, in Hamburg, as a teacher of the handicapped. In that same year she undertook a study trip to France, staying in Paris and Dijon, where she trained to be an interpreter. In 1928, she returned to her family home after her mother's health deteriorated in order to look after the household. Upon her mother's death in March 1930, she worked as her father's secretary.

In the late 1920s her poems began to appear in various literary journals and anthologies. Her third volume, Die Frau und die Tiere[2] came out under a Jewish publisher's imprint in August 1938 but was pulped after the Kristallnacht pogrom in November of that year. The Chodziesner family, as a result of the intensification of the persecution of Jews under National Socialism, had to sell its house in the Berlin suburb of Finkenkrug, which, to Kolmar's imagination became her 'lost paradise' (das verlorene Paradies), and was constrained to take over a floor in an apartment block called 'Jewshome' (Judenhaus) in the Berlin suburb of Schöneberg.

From July 1941 she was ordered to work in a forced labour corvée in the German armaments industry. Her father was deported in September 1942 to Theresienstadt where he died in February 1943. Gertrud Kolmar was arrested in the course of a factory raid on 27 February 1943, and transported on 2 March to Auschwitz, though the date and circumstances of her death are not known.

Literary standing

Post-war critics have accorded Kolmar a very high place in literature. Jacob Picard, in his epilogue to Gertrud Kolmar: Das Lyrische Werk described her both as 'one of the most important woman poets' in the whole of German literature, and 'the greatest lyrical poetess of Jewish descent who has ever lived'. Michael Hamburger withheld judgement on the latter affirmation on the grounds he was not sufficiently competent to judge, but agreed with Picard's high estimation of her as a master poet in the German lyrical canon.[3] Patrick Bridgwater, citing the great range of her imagery and verse forms, and the passionate integrity which runs through her work, likewise writes that she was 'one of the great poets of her time, and perhaps the greatest woman poet ever to have written in German'.[4]

Posthumous honours

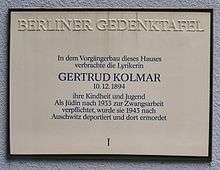

On the 24 February 1993, a plaque in her honour was placed at Haus Ahornallee 37, in Berlin's Charlottenburg suburb. Her name has also been given to a street in Berlin which runs directly through the former site of Hitler's Reich Chancellery, near the location of the Führerbunker.

Works

- Original language

- Gedichte, Berlin 1917

- Preußische Wappen, Berlin 1934

- Die Frau und die Tiere, Berlin 1938

- Welten, Berlin 1947

- Das lyrische Werk, Heidelberg [and others] 1955

- Das lyrische Werk, Munich 1960

- Eine Mutter, Munich 1965

- Die Kerze von Arras. Ausgewählte Gedichte. Berlin and Weimar: Aufbau-Verl., 1968

- Briefe an die Schwester Hilde, Munich 1970

- Das Wort der Stummen. Nachgelassene Gedichte, edited, and with an afterword by Uwe Berger and Erinnerungen an Gertrud Kolmar (Memories of Gertrude Kolmar) by Hilde Benjamin, Berlin: Buchverl. Der Morgen, 1978

- Susanna, Frankfurt am Main, 1993; on 2 CDs, Berlin: Herzrasen Records, 2006

- Nacht, Verona 1994

- Briefe, Göttingen 1997

- English translation

- Dark Soliloquy: the Selected Poems of Gertrud Kolmar, Translated with an Introduction by Henry A. Smith. Foreword Cynthia Ozick. Seabury Press, NY, 1975 ISBN 978-0-8164-9199-5 or ISBN 0-8164-9199-2

- A Jewish Mother from Berlin: A Novel; Susanna: A Novella, tr. Brigitte Goldstein. New York, London: Holmes & Meier, 1997. ISBN 978-0-8419-1345-5

- My Gaze Is Turned Inward: Letters 1934-1943 (Jewish Lives), ed. Johanna Woltmann, tr. Brigitte Goldstein. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8101-1854-6

References

- See, for example, Hamburger (1957), Bridgwater (1963) and Picard's epilogue to Das lyrische Werk

- Now the subject of an academic monograph. Cf. Kathy Zarnegin, Tierische Träume: Lektüren zu Gertrud Kolmars Gedichtband 'die Frau und die Tiere', M. Niemeyer, 1998

- Michael Hamburger, review of Gertrud Kolmar: Das Lyrische Werk, in Commentary, January 1957

- Patrick Bridgwater, (ed.) Twentieth-Century German Verse,(1963) rev.ed., Penguin 1968 p.xxiii

External links

- Gertrud Kolmar in the German National Library catalogue

- Collection of links to biographies and other information about Gertrude Kolmar at the library of the Free University of Berlin (in German)

- Krick-Aigner, Kirsten. "Gertrud Kolmar." Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 1 March 2009. Jewish Women's Archive

- Gertrud Kolmar Collection, AR 1346 Archival Collection at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York