Georges Wague

Georges Wague, born Georges Marie Valentin Waag, (14 January 1874 - 17 April 1965) was a French mime, teacher and silent film actor.

Georges Wague | |

|---|---|

Portrait in pastel of Georges Wague in Pierrot by Jules Chéret, 1909 | |

| Born | Georges Marie Valentin Waag 14 January 1874 Paris, France |

| Died | 17 April 1965 (aged 91) Menton, Alpes-Maritimes, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Mime and silent film actor |

Birth and education

Georges Marie Valentin Waag was born in Paris on 14 January 1874.[1] His parents were strict and devout. His mother died when he was nine, and he was placed in the school of the Brothers of the Christian doctrine on rue d'Assas in Paris. Here he helped with performances given by the association of young people from the parish of Saint-Sulpice, and began to recite poetry with this association. He qualified as an electrical engineer before entering the Conservatory of Dramatic Art of Paris as an auditor.[2] At the Conservatory he attended the course given by Dupont Vernon.

Early career

In the early 1890s Wague participated in the soirées of La Plume, the literary magazine founded by Léon Deschamps, where he was noticed for his verse recitals. Xavier Privas proposed to sing songs while Georges Wague mimed them, creating a new artistic expression they called "cantomime".[lower-alpha 1] In the cantomimes, which began in 1893 at the Café Procope, Wague performed on stage with a singer and piano in the wings. Often the character was Pierrot.[2] The established mime Félicia Mallet assisted Wague in developing his highly individual style during the early part of his career.[3] Cantomimes included Noël de Pierrot (1894) and Le Testament de Pierrot (1895).[2] Some were performed at Théâtre de la Bodinière in the Rue Saint-Lazare. Wague staged his first pantomime at the Théâtre Montparnasse in 1895, Le Voeu de Musette. Many others followed over the years.[2]

To revive his career after his return from military service in 1898, Georges Wague began to participate in soirées of the "Veillées artistiques de Plaisance". Cantomimes included Pierrot Chante (1899) and Sommeil Blanc (1899).[2] Sommeil blanc (White Sleep) was written for him by Xavier Privas, with music by Louis Huvey. Due to rivalry with other performers of cantomimes, Wague created a company with Christiane Mandelys (or Mendelys), who became his wife, to preserve his rights as inventor of the concept. With his troupe, he played La Roulotte (The Caravan) directed by Georges Chartron. He won success and began touring in France and abroad, leading to presentation of the last show at the Exposition Universelle (1900) where he played Pierrot parts such as unfaithful Pierrot and Christmas Pierrot.

Star

Georges Wague decided to move into white pantomime, where large gestures and movements are made, and the pantomime is dramatic. For this he changed his stage play: his mime consisted of gestures reduced to the simplest attitudes to express the full range of thought in constant movement. He did not use the conventional alphabet of mimes in this original form of expression.

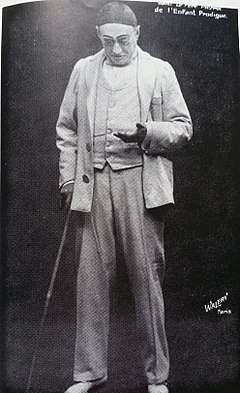

Georges Wague taught pantomime, notably to the writer Colette, with whom he made a tour from 1906 to 1912 and caused a scandal with presentations of La Chair (Flesh) where Colette was largely naked.[4] Wague performed in many stage pantomimes including Scaramouche, Barbe Bluette and L'homme aux poupées, and played silent roles in ballet and opera. Between 1907 and 1922, he also performed in more than forty films.[5] He started his film career with the silent film L'Enfant prodigue (The Prodigal Son) by Michel Carré, where he played a Pierrot. His last film performance was in 1922 in Faust by Gérard Bourgeois. He continued to play a white-faced Pierrot at the Opéra-Comique during the 1920s.[6] In 1925, he performed with the flamenco dancer Antonia Mercé y Luque, "La Argentina", in El amor brujo at the Théâtre Trianon-Lyrique.[7]

From 1916 Wague taught at the Conservatoire national supérieur d'art dramatique.[2] Wague taught mimes who went on the fame such as Christine Kerf, Caroline Otéro, Angèle Héraud and Charlotte Wiehé. He also taught actors and opera singers how to use their bodies to express their feelings. This skill was much neglected in opera, where often the singers were chosen for their voice rather than their appearance and had little acting ability.[2] Wague collaborated with the mime and actor Jean-Louis Barrault when he played Jean-Gaspard Deburau in the 1943 film Children of Paradise, the basis for his 1946 mime piece Baptiste.[8]

Georges Wague was awarded the Grande médaille de vermeil by the city of Paris in 1962. He died on 17 April 1965 at Menton in the Alpes-Maritimes, aged 91.[1]

Views

Although Georges Wague began his career in Pierrot's costume, he ultimately dismissed the work of Jean-Gaspard Deburau ("Baptiste") as puerile and embryonic, averring that it was time for Pierrot's demise in order to make way for "characters less conventional, more human."[9][10] Wague criticized the classical Italian mime tradition in a 1908 interview, contrasting it to the new form of mime emerging in France. He said,

The first school - that of the Italian tradition - has one great fault that kills the rest. That is, it has at its disposition a fairly limited number of restrained movements of which many are purely conventional - a sort of mute alphabet ... The public can't understand these without being initiated. ... The new school - the French one - is more sober and true. It endeavors to depict a feeling or state of mind solely through the general attitude of the body and the expressions that the extraordinary mobility of the face makes almost unlimited. All of these felt impressions find ample reflection - so to speak - in the facial features that they infinitely modify, change and transform ... All of the dramatic arts have changed, why not pantomime?[11]

Wague saw the art of pantomime as capable of far greater range than spoken words, particularly in communicating feelings. He said, "With the blaze of a look, the cadence of a step, a torso rotation, a wrinkling of the features, a mime artist can characterize ulterior motives such as hatred, remorse, desire, enjoyment or disgust, which the most warmly described and dramatically well-stated phrases can only superficially provide."[12]

Selected films

- 1907: L'Enfant prodigue (The Prodigal Son) by Michel Carré

- 1917: Le Bonheur qui revient (The Happiness that returns) by André Hugon

- 1922: Faust by Gérard Bourgeois

References

Notes

- Cantomime from "canto" (singing) and mime

Citations

- Acte de naissance 6/1874/135.

- Lust 2002, p. 62.

- Gaudreault, Dulac & Hidalgo 2012, p. 106.

- Tilburg 2007, p. 63.

- Gaudreault, Dulac & Hidalgo 2012, p. 107.

- Lust 2002, p. 92.

- Bennahum 2000, p. 85.

- Lust 2002, p. 79.

- Wague 1913, p. 8-11.

- Rémy 1964, p. 27.

- Gaudreault, Dulac & Hidalgo 2012, p. 106-107.

- Gaudreault, Dulac & Hidalgo 2012, p. 110.

Sources

- "Acte de naissance 6/1874/135", Archives numérisées de l'état civil de Paris Date and place of death noted in the margin.

- Bennahum, Ninotchka (2000). Antonia Merce,́ "La Argentina": Flamenco and the Spanish Avant Garde. Wesleyan University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8195-6383-5. Retrieved 2013-06-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaudreault, André; Dulac, Nicolas; Hidalgo, Santiago (2012-07-02). A Companion to Early Cinema. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3231-5. Retrieved 2013-06-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lust, Annette (November 2002). From the Greek Mimes to Marcel Marceau and Beyond: Mimes, Actors, Pierrots, and Clowns : a Chronicle of the Many Visages of Mime in the Theatre. SCARECROW PressINC. ISBN 978-0-8108-4593-0. Retrieved 2013-06-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rémy, Tristan (1964). Georges Wague: le mime de la belle époque. G. Girard. Retrieved 2013-06-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tilburg, Patricia (2007). "The Triumph of the Flesh: Women, Physical Culture, and the Nude in the French Music Hall". Radical History Review. 98.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wague, Georges (1913). La Pantomime moderne, conférence prononcé le 19 janvier 1913, dans la salle de l'Université Populaire. Paris: Editions de l'Université Populaire.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)