George Walter (1790–1854)

George Walter (1790–1854) was an English entrepreneur, known for his involvement with early railways of the 1830s.[1]

Early life

He was the second son of the Rev. Edward Newton Walter.[2] He became a Royal Marines 2nd lieutenant in 1811.[3] Towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars he was serving on HMS Chatham. Well-connected, he was a member of the London Stock Exchange from 1823 to 1828. In 1825 he was involved in the unrealised project of Nicholas Wilcocks Cundy of a Portsmouth-London ship canal. He founded in 1829 the General Annuity Endowment Association, later the Sovereign Life Assurance Company.[4][5][6]

Railway entrepreneur

Walter was one of the founders of the Southampton and London Railway and Dock Company, in 1831, with Abel Rous Dottin, and Robert Johnston (1783–1839) from Jamaica. The company failed.[4][7][8] George Thomas Landmann in October 1831 brought Walter into planning for the London and Greenwich Railway, and an initial meeting was held in Dottin's house in Argyle Street, London. The company's base was Walter's insurance office.[4]

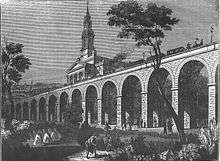

In 1831, Walter took the position of secretary of the London & Greenwich; in 1835, he became Resident Director (i.e. managing director). At that time, the London Bridge – Greenwich Railway Viaduct was close to completion, and the prospect existed that the London & Greenwich would be the first railway running into the metropolis. The capital position of the company was not healthy, however, and the raising of additional finance depressed the share price.[9][10] In July 1837, Dottin and Walter resigned as directors.[11]

In 1835 Walter founded and subsidised the Railway Magazine, having seen the potential in the Mechanics' Magazine and its railway promotion; he brought in John Yonge Akerman as its editor.[12] It was the first specialist railway periodical, and Walter used it to publicise the London & Greenwich, where Akerman was his replacement as secretary, and his other interests. In 1836 he sold it to John Herapath.[13][14]

Later life

In 1844 Walter became manager of the company manufacturing Kamptulicon; which was wound up in 1851.[15][16] In the same year his partnership with Ebenezer Gough, to manufacture Kamptulicon, also ended.[17]

Walter died at Prittlewell, Essex on 24 August 1854.[18]

Family

Walter married twice, and had 12 children.[15] They included Dottin Alleyne Walter, an architect known also as an antiquarian.[19]

Notes

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. pp. 30/1 caption. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- The History of Rochford Hundred. A. Harrington. 1867. p. 387.

- Great Britain. Admiralty (1855). The Navy List. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 320.

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- Peach, Annette. "Cundy, Thomas, the elder". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6906. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Wellcome Library, Limehouse 1882, Report of the Medical Officer of Health for Limehouse". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Stephanie Barczewski (8 December 2011). Titanic 100th Anniversary Edition: A Night Remembered. A&C Black. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4411-9308-7.

- Mason, George Champlin (1884). Reminiscences of Newport ...Extra Illustrated. Edition D. Internet Archive. Charles E. Hammett, Jr. p. 187. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. pp. 16 and 50. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- Opening of the Greenwich Railway [on 14th December, 1836]. Berger. 1836. p. 59.

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- J. E. C. Palmer (edited by H. W. Paar), Authority, idiosyncracy, and corruption in the early railway press, 1823–1844, Journal of the Railway and Canal Historical Society, July 1995, pp. 442–457, at p. 447.

- Steve Schifferes; Richard Roberts (27 August 2014). The Media and Financial Crises: Comparative and Historical Perspectives. Routledge. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-317-62452-3.

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- Ronald Henry George Thomas (1986). London's First Railway: The London and Greenwich. B. T. Batsford Limited. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7134-5414-7.

- https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/21206/page/1202/data.pdf

- The London Gazette. T. Neuman. 1851. p. 91.

- The Gentleman's Magazine. F. Jefferies. 1854. p. 412.

- The Antiquary. 33. London: Elliot Stock. 1880–1915. pp. 229–30. Retrieved 13 April 2017.CS1 maint: date format (link)