George Vaughan Maddox

George Vaughan Maddox (1802–27 February 1864)[1] was a nineteenth-century British architect and builder, whose work was undertaken principally in the town of Monmouth, Wales, and in the wider county. Working mainly in a Neo-Classical style, his extensive output made a significant contribution to the Monmouth townscape. The architectural historian John Newman writes that his buildings "give(.) Monmouth its particular architectural flavour. For two decades from the mid-1820s he put up a sequence of public buildings and private houses in the town, in a style deft, cultured, and only occasionally unresolved."[2] The Market Hall and 1-6 Priory Street are considered Maddox's "most important projects"[3].

George Vaughan Maddox | |

|---|---|

Kingsley House (left), built to Maddox's design and his home for much of his life | |

| Born | 1802 |

| Died | 27 February 1864 (age 61/62) Hempsted, Gloucestershire |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Years active | 1820s–1840s |

Life and works

Maddox was born in 1802, the son of another architect, John Maddox,[4] who also worked in the county. Maddox designed some of Monmouth's most notable buildings, including the Market Hall, "his major work",[5] the Beaufort Arms Hotel, the Methodist Church,[6][7] the Masonic Hall, Kingsley House, Oak House, and 18 St James Street,.[6][8][9]

For much of his life, Maddox lived at 8 Monk Street, Monmouth.[10] In the early 1830s, Maddox won a competition organised by the Borough Council in Monmouth, to design a new scheme which would relieve Church Street of through traffic, and provide new accommodation for slaughterhouses and a new Market Hall to replace the market beneath the Shire Hall which faced disruption because of the need to extend the accommodation for the Assizes. Maddox proposed a new carriage road running above the bank of the River Monnow, supported by a viaduct. The Market Hall, with a crescent-shaped frontage of Bath Stone in a Doric style, and an Ionic cupola and clerestory above the central part of the building, was built on one side of the road, and a long convex stuccoed frontage, 1-6 Priory Street, on the opposite side.[11] The new slaughterhouses, comprising 24 rooms with openings onto the river so that their waste would drain directly into it, were sited beneath the sandstone arches of the viaduct. The new road – now Priory Street – was opened in 1834, and the Market Hall in 1840.[12][13]

His other works include Pentwyn at Rockfield, which he built as his own residence in 1834–37;[14] and Croft-y-Bwla, a villa midway between Monmouth and Rockfield[15] which was the home of Alexander Rolls and his first wife Kate Steward Rolls. He also undertook a limited early re-building of The Hendre,[16] and carried out work in Commercial Street, Pontypool.[17] Cadw suggests that Maddox was also the architect of the main block of Piercefield House, near Chepstow, working to designs by Sir John Soane.[18] Given the date of Maddox's birth, and the construction period for Piercefield, this seems unlikely. The architectural historian John Newman follows the more conventional attribution to Soane himself.[19]

Maddox died at Hempsted Rectory, Gloucestershire on 27 February 1864.[20]

Gallery

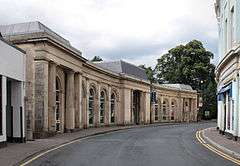

The Market Hall in Priory Street, Monmouth; the first storey in the centre of the building was destroyed by fire in 1963

The Market Hall in Priory Street, Monmouth; the first storey in the centre of the building was destroyed by fire in 1963 The slaughterhouses beneath the Market Hall

The slaughterhouses beneath the Market Hall

References

- Brodie (2001)

- Newman 2000, p. 394.

- Kissack 1975, p. 298.

- Public Architecture, House of Correction, Usk Archived 26 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 19 January 2012; "the only son of James Maddox, a builder of Monmouth, and was doubtless related to George Maddox" (Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840, 3rd ed. 1995, s.v. "Maddox, George Vaughan".

- Newman 2000, p. 44.

- NONCONFORMITY IN MONMOUTH, Newsletter No. 29, Capel, The Chapels Heritage Society, accessed January 2012

- Newman 2000, p. 399.

- Kissack 2003, p. 35.

- Bly 2012, p. 10.

- Building permission Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed January 2012

- Newman 2000, pp. 405–6.

- Bly 2012, p. ?.

- Kissack 2003, p. xii.

- Newman 2000, p. 516.

- Newman 2000, p. 411.

- Newman 2000, p. 250.

- Newman 2000, p. 479.

- "Listed Buildings - Full Report - HeritageBill Cadw Assets - Reports". Cadwpublic-api.azurewebsites.net. 14 February 2001. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Newman 2000, p. 471.

- Brodie 2001, p. 121.

Sources=

- Bly, Phil (2012). Guide to the complete Monmouth Heritage Blue Plaque Trail. Monmouth: Monmouth Civic Society. OCLC 797974800.

- Brodie, Antonia (2001). Directory of British Architects 1834–1914: L–Z. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-4963-4.

- Kissack, Keith (1975). Monmouth: The Making of a County Town. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 9780850332094. OCLC 255539468.

- Kissack, Keith (2003). Monmouth and its Buildings. Woonton Almeley: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-904396-01-7. OCLC 55143853.

- Newman, John (2000). Gwent/Monmouthshire. The Buildings of Wales. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-300-09630-9.