George Merrill (gay activist)

George Merrill (1867 – 16 January 1928) was the life partner of English poet and LGBT activist Edward Carpenter.[2]

George Merrill | |

|---|---|

George Merrill by Lena Connell | |

| Born | George Merrill 1867[1] |

| Died | 16 January 1928 (aged 60–61) |

| Partner(s) | Edward Carpenter (1891–1928) |

Merrill was a working-class man who grew up in the slums of Sheffield; he had no formal education.[1] He met Edward Carpenter on a train in 1891, and moved into Carpenter's home, a small holding at Millthorpe, Derbyshire[3] in February 1898, when Carpenter's previous domestic help, George Adams and his family, moved out when Adams retired. Merrill had previously worked in a newspaper office, a hotel, and in an ironworks. He was always officially Carpenter's servant, and he undertook the cooking and cleaning in the home, decorating and placing flowers in every room. Carpenter noted that "George in fact was accepted and one may say beloved by both my manual worker friends and my more aristocratic friends." He had a fine baritone voice and liked to sing comical songs.[4]

Merrill arrived in a blizzard, "trundling with the help of two boys all his worldly goods in a handcart over the hills, and through a disheartening blizzard of snow."[4] His arrival was commemorated by Carpenter in the poem "Hafiz to the Cupbearer", part of Carpenter's Towards Democracy which was published in stages between 1882 and 1902.[5][6]

The two lived openly as a couple for almost forty years, until Merrill's death in 1928.[7] Carpenter died the following year and was buried beside Merrill.[1]

The relationship between Carpenter and Merrill was the inspiration for E. M. Forster's novel Maurice, and the character of the gamekeeper Alec Scudder was in part modelled after George Merrill.[8][9] The novelist D. H. Lawrence read the manuscript of Maurice, which was not published until after Forster's death. The manuscript and Carpenter and Merrill's rural lifestyle influenced Lawrence's 1928 novel Lady Chatterley's Lover, which also involves a gamekeeper becoming the lover of a member of the upper classes.[10][11]

Gallery

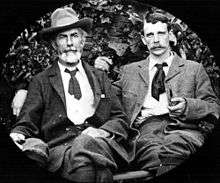

Edward Carpenter and Merrill, c. 1900.

Edward Carpenter and Merrill, c. 1900. The grave of Merrill and Edward Carpenter at the Mount Cemetery, Guildford, Surrey.

The grave of Merrill and Edward Carpenter at the Mount Cemetery, Guildford, Surrey.

References

- Rowbotham, Sheila (2008). Edward Carpenter: a life of liberty and love. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-295-0.

- Bailey, Quentin (2002) "Heroes and Homosexuals: Education and Empire in E. M. Forster" in Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 48, No. 3 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 324-347.

- Historic England. Millthorpe and Edward Carpenter. Retrieved 11 August 2020

- Carpenter, Edward (1916) My Days And Dreams Being Autobiographical Notes. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- Carpenter, Edward (2018) Towards Democracy. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Franklin Classics. (Reprint of the original published 1882-1902) ISBN 978-0342891542

- Pierson, Stanley (1970) "Edward Carpenter, Prophet of a Socialist Millennium" in Victorian Studies Vol. 13, No. 3 (Mar., 1970), pp. 301-318.

- James, Solomon (2017) "Edward Carpenter: Radical Mystic and Lover". Introduction to: Carpenter, Edward On Friendship and Love: A Reader, p. 5. Azafran Books. ISBN 978-0995655799.

- Symondson, Kate (25 May 2016) E M Forster’s gay fiction . The British Library website. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Rowse, A. L. (1977). Homosexuals in History: A Study of Ambivalence in Society, Literature, and the Arts. New York: Macmillan. pp. 282–283. ISBN 0-88029-011-0.

- King, Dixie (1982) "The Influence of Forster's Maurice on Lady Chatterley's Lover" in Contemporary Literature Vol. 23, No. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 65-82.

- Delaveny, Emile (1971) D. H. Lawrence and Edward Carpenter: A Study in Edwardian Transition. New York: Taplinger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0800821807

External links

- George Merrill's biographic sketch at Find a Grave

- Edward Carpenter, George Merrill, a true history, & study in psychology (1913). Transcription of the unpublished typescript.

- Edward Carpenter, My days and dreams, being autobiographical notes, Allen & Unwin, 1916, chapter 9.