George Lily

George Lily (died 1559) was an English Roman Catholic priest, humanist scholar, biographer, topographer and cartographer.

Life

George Lily was born in London, the son of William Lily the grammarian, and his wife Agnes. He may have attended St Paul's School, where his father was High Master; and he may have become a commoner of Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1528.[1] He subsequently entered the service of Reginald Pole, and in the years that followed shared some of Pole's self-imposed exile in France and Italy. Pole awarded him, by 1535, a prebend in Wimborne Minster. Also by this date, however, he was studying at the University of Padua, under such scholars as Giovanni Battista Egnazio, Lazarus Buonamici, and Fausto da Longiano. In 1538–39 he was living in Rome; and he afterwards travelled with Pole to Viterbo. At some point before 1543 he was outlawed in England for treason, presumably on account of his connections with Pole, who was by now a Cardinal and unofficial leader of the English Catholic church in exile.[1]

Between 1549 and 1554 Lily served three terms as Pole's deputy as warden of the English Hospice in Rome.[1] In 1554 he followed Pole to Brussels; and in November 1555 the two returned to England, now again a Catholic realm under Queen Mary I. Pole was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury in March 1556; while Lily became his domestic chaplain, and was also collated to the prebend of Kentish Town or Cantlers, in St. Paul's Cathedral, on 22 November 1556, and to the first prebend of Canterbury Cathedral probably on 10 March 1558.[1]

Lily died on 14 July 1559 in Canterbury.[1] He is thought to have been buried close to his father in the churchyard of St Paul's Cathedral.[2]

Works

Writings

Lily was a major contributor to the Descriptio Britanniae, Scotiae, Hyberniae et Orchadum, a chorography of the British Isles conceived by Paolo Giovio, Bishop of Nocera, which was published in Venice in 1548. As well as supplying information to Giovio for the geographical descriptions, Lily was the author of several self-contained historical appendices: "Virorum aliquot in Britannia qui nostro seculo eruditione & doctrina clari, memorabilesque fuerunt elogia", a collection of short biographies of English humanist scholars (including his own father, William), which was dedicated to Giovio; "Nova et Antiqua Locorum Nomina in Anglia et in Scotia", a table of ancient and modern place and tribal names; "A Bruto ... omnium in quos variante fortuna Britanniae imperium translatum brevis enumeratio", a discussion of the early history of Britain, in which Lily expressed scepticism about the legendary foundation of the realm by Brutus; "Lancastrii et Eboracensis de regno contentiones", an account of the Wars of the Roses; and "Regum Angliae genealogia", a genealogy of the Kings of England.

Lily has also been credited as author of "Catalogus sive Series Pontificorum et Caesarum Romanorum" (a catalogue of Roman Popes and Emperors), a "Life of John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester", and an account of the life of Thomas Cranmer ("De vita, moribus, et fine Thomae Cranmeri"); but the latter two of these attributions, at least, are no longer upheld.[2][1]

Cartography

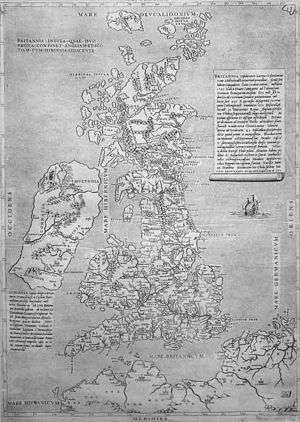

Almost certainly intended as a companion-piece to the Descriptio Britanniae, Lily drew the first map of the British Isles (at a reasonably detailed scale) to be printed.[3][4][5] It was engraved on two plates and published in Rome in 1546. The map is recognisably a relation of the 14th-century Gough Map, although the orientation has been reversed (West is at the top of the sheet), and many minor improvements have been made. The Scottish coastline, in particular, is considerably more accurate than that on the Gough Map, but Lily's sources for this are not known. The map was pirated on several occasions in Italy; and Lily and Pole appear to have carried the plates back to England with them, as they were reworked by the engraver Thomas Geminus for a London edition published in 1555.

It has also been suggested that Lily had a hand in the large-scale "Copperplate Map" of London, printed in about 1559.[6]

References

- Mayer 2008.

- Cooper 1892.

- Lynam 1934.

- Shirley, R.W. (1991). Early Printed Maps of the British Isles, 1477–1650 (2nd ed.). East Grinstead: Antique Atlas. pp. 20–22. ISBN 0951491423.

- Delano-Smith, Catherine; Kain, Roger J.P. (1999). English Maps: a history. London: British Library. pp. 52–3, 61–3. ISBN 0712346090.

- Barber, Peter (2001). "The Copperplate Map in context". In Saunders, Ann; Schofield, John (eds.). Tudor London: a map and a view. London Topographical Society Publication. 159. London: London Topographical Society. pp. 16–32 (22–3). ISBN 0902087452.

- Attribution

![]()

Further reading

- Lynam, Edward (1934). The Map of the British Isles of 1546. Jenkinstown, Pa.

- Mayer, T.F. (2008) [2004]. "Lily, George (d. 1559)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16663. (subscription required)