George Dunbar, 10th Earl of March

George de Dunbar, 10th Earl of Dunbar and March[1][2] (1338–1420),[3] 12th Lord of Annandale and Lord of the Isle of Man,[4] was "one of the most powerful nobles in Scotland of his time, and the rival of the Douglases."[5]

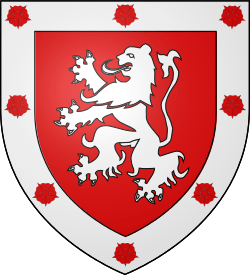

Gules a lion rampant Argent on a bordure of the same eight roses of the field

Family

Pitscottie states that this George is a son of John de Dunbar of Derchester & Birkynside, by his spouse Geiles (or Isabella), daughter of Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray (d. 1332).[6] John was son of Alexander de Dunbar, Knt. (a younger son of Patrick de Dunbar, 7th Earl of March), although some genealogies place John as a son of Patrick de Dunbar, 8th Earl of March.

If John's father Alexander was a younger brother of Patrick de Dunbar, "8th" Earl of March, then John is not a younger brother of Sir Patrick de Dunbar, 9th Earl of March.

George succeeded his first cousin once removed Sir Patrick in his honours and estates, and appears in a charter dated 28 June 1363; and is second witness, styled 'cousin' of Sir Patrick (rather than 'nephew') and his wife 'black' Agnes, in another charter signed at Dunbar Castle on 24 May 1367.[7] "Robetus de Lawedre, consanguineus noster" (a cousin) witnessed a charter of "Georgii comitis Marchie" relating to Sorrowlessfield, a still extant property on the (A68) road south of Earlston, Berwickshire, in the reign (1390–1406) of Robert III,[8] indicating both his extended family and that he was active in the management of the Dunbar family estates during Robert's reign.

Campaigns and intrigue

The Earl of March acquired the estates centred on the castles of Morton and Tibbers, with Morton likely becoming the centre of administration for both.[9]

The Earl of March accompanied James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas, in his incursion into England, and after the Battle of Otterburn (1388) he took command of the Scots, whom he conducted safely home. His daughter Elizabeth was betrothed by contract to David Stewart, Duke of Rothesay, son of King Robert III and heir to the throne, but Archibald Douglas, 3rd Earl of Douglas, 'The Grim', protested against the match, and through the influence of the Duke of Albany had the contract annulled, and had the prince married to his own daughter Marjory instead.[5]

Exile to England

In consequence of this slight upon his family's honour, George renounced his allegiance to Robert III and retired into England, placing himself under the protection of King Henry IV. On 28 June 1401, Henry granted, by Letters Patent, to "George de Dunbarre earl of the March of Scotland and Cristiana his wife" the lordship of Somerton in Lincolnshire, and the heirs male of their bodies, to be held by homage and military service. On the same day Henry gave "George de Dunbarre earl of the March of Scotland" £100 sterling per annum "of his special favour" and in October granted him 'costs' of £25/9s/7d; and granted his wife "Cristiana countess of Dunbarre" £40/19s/3d "for her charges and expenses coming from the North at his command, to prosecute certain matters touching her husband, herself, and their heirs".[10]

Battles

In 1401 he made a wasteful inroad into Scotland, and in June 1402 he was victorious against a small Scottish force at the Battle of Nesbit Moor. At the subsequent Battle of Homildon Hill he again fought on the English side.[5]

In the summer of 1403 the Percies declared open revolt against King Henry IV and raised their standard of revolt at Chester. A plan was hatched to seize the King's son, the young Prince of Wales, at Shrewsbury. The plan was foiled by the extreme speed with which Henry IV moved once he heard details of the revolt. "Egged on by his very competent and energetic ally, the renegade Scotsman, George Dunbar", he drove his men across the Midlands towards Shrewsbury, raising more troops as he went.[11] The Battle of Shrewsbury took place on 21 July 1403, with Dunbar fighting on the side of Henry IV.[12] It was a royal victory and the revolt was, for the moment, over.

Estates

Thereafter in the same year "George de Dunbar earl of the March of Scotland" petitioned (Parliamentary Petitions, No.961) Henry IV stating that he had lost all his castles, lordships, goods and chattels in Scotland on account of his being his liegeman, and asked the King to "ordain in this parliament that if any conquest is made in the realm of Scotland, the petitioner may have restoration of his castles, &c., and also his special protection for all dwelling in the earldom of March who come to his allegiance hereafter". This was endorsed by the King.[13]

On 21 January 1403/4 "George de Dunbarre earl of the March of Scotland" received a £100 annuity from Henry IV.[14]

Between 14 and 18 August 1403, King Henry granted George de Dunbar, Earl of March, the ward of the manors and lordships of Kyme and Croftes in Lincolnshire, and a house and chattels in Bishopsgate, City of London, for life, which had previously belonged to the late Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester, and was forfeited by his rebellion.[15]

Under a Letters Patent, "the King's cousin, George de Dunbarre, Earl of March of Scotland", for "his daily service and great costs" was given the manor of Clippeston in Shirewood by King Henry IV on 10 June 1405. In addition, on 14th of the following month, the King gave him the ward of the lands of the late Thomas Umfraville in Haysille on Humber in York, till the majority of Gilber his heir, or his heirs in succession if he dies in minority.[16]

In addition he shared in the forfeited estates of the attainted Thomas Bardolf, 5th Lord Bardolf (who later fell with Percy at the Battle of Bramham Moor in February 1408). However, as the following decree shows, George did not retain them all: "27 April 1407. The King to the sheriff of Lincoln. Referring to the late plea in Chancery between Amicia wife of Thomas, late lord of Bardolf, and George de Dunbarre regarding certain lands in Ruskynton forfeited by Thomas, which had been granted by the King to George, with the manor of Calthorpe, the half of Ancaster (and many others), wherein it was adjudged that Rusynton should be excepted from the grant and restored to her with the rents, etc., from 27 November 1405, drawn by George, - the King orders him to restore the same to Amicia. Westminster. [Close, 9 Henry IV. m.17.]".[17]

Return to Scotland

Through the mediation of Sir Walter Haliburton of Dirleton,[18] reconciliation with the Douglases was effected in 1408, and he was allowed to return to Scotland the following year, taking possession of his earldom of March, but said to be deprived of the lordship of Annandale.[19]

In 1411 he was one of the Scottish Commissioners for negotiating a truce with England, but died of a contagious fever, in 1420, at the age of 82.[5]

He married Christina, daughter of Alan de Wyntoun and had at least eight children, including:

- Sir George, 11th Earl of Dunbar & March

- Columba de Dunbar, Bishop of Moray[20][21]

- Sir Gavin de Dunbar of Cumnock, Ayrshire.[20]

- Patrick de Dunbar of Biel, Haddingtonshire, living 1452.[22]

- Sir David de Dunbar of Cockburn, whose daughter, Marjorie/Margaret de Dunbar, married Alexander Lindsay, 4th Earl of Crawford[23]

- Janet, who married as her first husband, Sir John Seton of Seton, Knt.,(died 1441)[24][25] She married secondly, Adam Johnstone of that Ilk (in Annandale).[26]

- Marjory, who married Sir John Swinton, 15th of that Ilk, killed at the Battle of Verneuil, France, in 1424.[27]

References

- Brown, Peter, publisher, The Peerage of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1834: 145, where he is stated to be the 10th earl.

- Anderson, William, The Scottish Nation, Edinburgh, 1867, vol.iv, p.74, where he is given as the 10th earl

- Anderson (1867), vol.iv:74, where it is stated "he died of a contagious fever in 1420, aged 82

- Angus, William, 'Miscellaneous Charters 1315-1401' in Miscellany of The Scottish History Society volume five, Edinburgh, 1933:27 where he is described as "Georgius de Dumbarr comes Marchie et dominus vallis Annandie et Mannie" in a charter dated 30 July 1372

- Anderson (1867), vol.iv:74

- Bain, Joseph, FSA (Scot), editor, Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland 1357 - 1509, Edinburgh, 1888, vol.iv: xx - xxv. (If Pitscottie made an erroneous assumption, George would likely be a son of Sir Patrick Dunbar (son of Alexander de Dunbar)).

- Bain (1888),pps: xx - xxv

- Young, James, Historical References to the Scottish Family of Lauder, Glasgow, 1884, p.19

-

- Dixon, Piers; Anderson, Iain; O'Grady, Oliver (2015), The evolution of a castle, Tibbers, Dumfriesshire. Measure and geophysical survey, 2013–14 (PDF), Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and the Castle Studies Trust, pp. 3–4

- Dixon, Piers; Anderson, Iain; O'Grady, Oliver (2015), The evolution of a castle, Tibbers, Dumfriesshire. Measure and geophysical survey, 2013–14 (PDF), Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and the Castle Studies Trust, pp. 3–4

- Bain (1888), vol.iv, pps:125 & 130, nos.602 & 623.

- Earle, Peter, The Life and Times of Henry V, London, 1972, p.56-7, ISBN 978-0-297-99428-2

- Dunbar, Sir Alexander H., Bt., Scottish Kings, Edinburgh, 1899, p.177

- Bain (1888), vol.iv, p.132-3, no.634.

- Bain (1888), vol.iv, p.137, no.650.

- Bain (1888), vol.iv, p.133, nos.637, 639.

- Bain (1888), vol. iv, p.142-3, nos.681/685.

- Bain (1888), vol.iv. p.150, no.732

- Rogers, Charles,LL.D., Genealogical Memoirs of the family of Sir Walter Scott, Bt., with his Memorials of the Halibirtons, London, 1877: xxx

- Brown (1834), Peerage, 145

- Burke, Sir Bernard, Ulster King of Arms, Burke's Dormant, Abeyant, Forfeited, and Extinct Peerages, London, 1883:606

- Lindsay, The Rev., & Hon., E.R., and Cameron, A.I.,Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome 1418 - 1422, Scottish History Society, Edinburgh, 1934:37-8, where he is described as "a son of George, 10th Earl of Dunbar and Earl of March" and "of a race of earls of Royal stock", the Supplication being dated at Florence, 1 May 1419.

- The Great Seal of Scotland, no.547, confirmed 24th April 1452. In this charter he and his brother David are both mentioned as brothers of George, earl of March.

- A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire, by Sir Bernard Burke.

- Anderson (1867), vol.viii:437

- Burke (1883),Dormant :606, where he is called Lord John Seton (presumably after Sir Richard Maitland's House of Setoun where he is also called Lord John)

- Burke's Dormant, Abeyant, Forefeited, and Extinct Peerages by Sir Bernard Burke, Ulster King of Arms, London, 1883, p.606.

- Burke, Messrs. John & John Bernard, The Royal Families of England Scotland and Wales, with their Descendants, London, 1851, volume 2, pedigree XXV

- Townend, Peter, editor, Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 105th edition, London, 1970, p. 913.

- Cokayne, G. E., et al., The Complete Peerage, under 'Dirletoun'.