Chesed

Chesed (Hebrew: חֶסֶד, also Romanized ḥesed) is a Hebrew word.

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Red-outline heart icon |

|

Types of love

|

In its positive sense, the word is used of kindness or love between people, of the devotional piety of people towards God as well as of love or mercy of God towards humanity. It is frequently used in Psalms in the latter sense, where it is traditionally translated "lovingkindness" in English translations.

In Jewish theology it is likewise used of God's love for the Children of Israel, and in Jewish ethics it is used for love or charity between people.[1] Chesed in this latter sense of "charity" is considered a virtue on its own, and also for its contribution to tikkun olam (repairing the world). It is also considered the foundation of many religious commandments practiced by traditional Jews, especially interpersonal commandments.

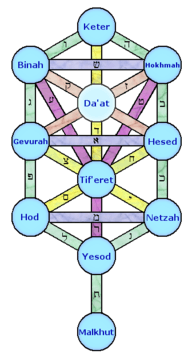

Chesed is also one of the ten Sephirot on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. It is given the association of kindness and love, and is the first of the emotive attributes of the sephirot.

Etymology and translations

| Look up חסד in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The root chasad has a primary meaning of "eager and ardent desire", used both in the sense "good, kind" and "shame, contempt".[2] The noun chesed inherits both senses, on one hand "zeal, love, kindness towards someone" and on the other "zeal, ardour against someone; envy, reproach". In its positive is used of mutual benevolence, mercy or pity between people, of devotional piety of people towards God, as well as the grace, favour or mercy of God towards people.[3]

It occurs 248 times in the Hebrew Bible. In the majority of cases (149 times), the King James Bible translation is "mercy", following LXX eleos. Less frequent translations are: "kindness" (40 times), "lovingkindness" (30 times), "goodness" (12 times), "kindly" (5 times), "merciful" (4 times), "favour" (3 times) and "good", "goodliness", "pity" (once each). Only two instances of the noun in its negative sense are in the text, translated "reproach" in Proverbs 14:34, and "wicked thing" in Leviticus 20:17.[3]

The translation of loving kindness in KJV is derived from the Coverdale Bible of 1535. This particular translation is used exclusively of chesed used of the benign attitude of YHWH ("the LORD") or Elohim ("God") towards his chosen, primarily invoked in Psalms (23 times), but also in the prophets, four times in Jeremiah, twice in Isaiah 63:7 and once in Hosea 2:19. While "lovingkindness" is now considered somewhat archaic, it is part of the traditional rendition of Psalms in English Bible translations.[4][5] Some more recent translations use "steadfast love" where KJV has "lovingkindness".

The Septuagint has mega eleos "great mercy", rendered as Latin misericordia. As an example of the use of chesed in Psalms, consider its notable occurrence at the beginning of Psalm 51 (חָנֵּנִי אֱלֹהִים כְּחַסְדֶּךָ, lit. "be favourable to me, Elohim, as your chesed"):

ἐλέησόν με ὁ θεός κατὰ τὸ μέγα ἔλεός σου (LXX)

Miserere mei, Deus, secundum misericordiam tuam (Vulgate)

"God, haue thou merci on me; bi thi greet merci." (Wycliffe 1388)

"Haue mercy vpon me (o God) after thy goodnes" (Coverdale Bible 1535)

"Haue mercie vpon mee, O God, according to thy louing kindnesse" (KJV 1611)

"Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy lovingkindness" (KJV 1769, RV 1885, ASV 1901)

"Favour me, O God, according to Thy kindness" (YLT 1862)

"Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy steadfast love" (RSV 1952)

"Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love" (NRSV 1989)

In Judaism, "love" is often used as a shorter English translation.[6][7][8] Political theorist Daniel Elazar has suggested that "chesed" cannot easily be translated into English, but that it means something like "loving covenant obligation".[9] Other suggestions include "grace"[10] and "compassion".[11]

Jewish ethics

In traditional musar literature (ethical literature), chesed is one of the primary virtues. The tannaic rabbi Simon the Just taught: "The world rests upon three things: Torah, service to God, and bestowing kindness" (Pirkei Avot 1:2). Chesed is here the core ethical virtue.

A statement by Rabbi Simlai in the Talmud claims that "The Torah begins with chesed and ends with chesed." This may be understood to mean that "the entire Torah is characterized by chesed, i.e. it sets forth a vision of the ideal life whose goals are behavior characterized by mercy and compassion." Alternatively, it may allude to the idea that the giving of the Torah itself is the quintessential act of chesed.[12]

In Moses ben Jacob Cordovero's kabbalistic treatise Tomer Devorah, the following are actions undertaken in imitation of the qualities of Chesed:[13]

- love God so completely that one will never forsake His service for any reason

- provide a child with all the necessities of their sustenance and love the child

- circumcise a child

- visiting and healing the sick

- giving charity to the poor

- offering hospitality to strangers

- attending to the dead

- bringing a bride to the chuppah marriage ceremony

- making peace between a person and another human being.

A person who embodies chesed is known as a chasid (hasid, חסיד), one who is faithful to the covenant and who goes "above and beyond that which is normally required"[14] and a number of groups throughout Jewish history which focus on going "above and beyond" have called themselves chasidim. These groups include the Hasideans of the Second Temple period, the Maimonidean Hasidim of medieval Egypt and Palestine, the Chassidei Ashkenaz in medieval Europe, and the Hasidic movement which emerged in eighteenth century Eastern Europe.[14]

Charitable organizations

In Modern Hebrew, חסד can take the generic meaning of "charity", and a "chesed institution" in modern Judaism may refer to any charitable organization run by religious Jewish groups or individuals. Charitable organizations described as "chesed institutions" include:

- Bikur cholim organizations, dedicated to visiting and caring for the sick and their relatives

- Gemach – an institution dedicated to gemilut chasadim (providing kindness), often with free loan funds or by lending or giving away particular types of items (toys, clothes, medical equipment, etc.). Such organizations are often named with an acronym of Gemilas chasadim such as Gemach or GM"CH. A community may have dozens of unique (and sometimes overlapping) Gemach organizations

- Kiruv organizations – organizations designed to increase Jewish awareness among unaffiliated Jews, which is considered a form of kindness

- Hatzolah – organizations by this name typically provide free services for emergency medical dispatch and ambulance transport (EMTs and paramedics)

- Chevra kadisha – organizations that perform religious care for the deceased, and often provide logistical help to their families relating to autopsies, transport of the body, emergency family travel, burial, running a Shiva home, and caring for mourners

- Chaverim (literally "friends") – organizations going by this name typically provide free roadside assistance and emergency help with mechanical or structural problems in private homes

- Shomrim (guardians) groups – community watch groups

Kabbalah

| The Sefirot in Kabbalah | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category:Sephirot | ||

The first three of the ten sephirot are the attributes of the intellect, while chesed is the first sephira of the attribute of action. In the kabbalistic Tree of life, its position is below Chokhmah, across from Gevurah and above Netzach. It is usually given four paths: to chokhmah, gevurah, tiphereth, and netzach (some Kabbalists place a path from chesed to binah as well.)

The Bahir[15] states, "What is the fourth (utterance): The fourth is the righteousness of God, His mercies and kindness with the entire world. This is the right hand of God."[16] Chesed manifests God's absolute, unlimited benevolence and kindness.[13]

The angelic order of this sphere is the Hashmallim, ruled by the Archangel Zadkiel. The opposing Qliphah is represented by the demonic order Gamchicoth, ruled by the Archdemon Astaroth.

See also

- Jewish views on love

- Divine love

- Agape (Greek, Christianity)

- Ishq (Arabic, Islam)

- Mettā (Pali, Buddhism)

References

- Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (2004). "Introduction and Annotations (Psalms)". The Jewish Study Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1280-1446. ISBN 9780195297515. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "Strong's H2616 - chacad". Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "Strong's H2617 - checed". Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Harris, R. Laird; Archer, Jr., Gleason L.; Waltke, Bruce K. "hesed". Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. 1. p. 307.

[Although] The word ‘lovingkindness’…is archaic, [it is] not far from the fullness of meaning of the word [chesed or hesed].

- Greenberg, Yudit Kornberg. Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions. 1. p. 268.

The Hebrew hesed (plural hasadim) is usually translated as "grace" or "loving-kindness", but sometimes also as "mercy" or "love".

- Adin Steinsaltz, In the beginning: discourses on Chasidic thought p. 140. My People's Prayer Book: Welcoming the night: Minchah and Ma'ariv ed. Lawrence Hoffman – Page 169

- Miriyam Glazer, Dancing on the edge of the world: Jewish stories of faith, inspiration, and love, p. 80. "Sefer Yetzirah", trans. Aryeh Kaplan, p. 86.

- "The Rabbinic Understanding of the Covenant", in Kinship & consent: the Jewish political tradition and its contemporary uses by Daniel Judah Elazar, p. 89

- Chesed "is the antidote to the narrow legalism that can be a problem for covenantal systems and would render them contractual rather than covenantal" Daniel Elazar, HaBrit V'HaHesed: Foundations of the Jewish System Archived 2010-06-21 at the Wayback Machine. Covenant and the Federal Constitution" by Neal Riemer in Publius vol. 10, No. 4 (Autumn, 1980), pp. 135–148.

- A Rabbinic anthology, World Pub. Co., 1963

- Schwarz, Rabbi Sidney (2008). Judaism and Justice: The Jewish Passion to Repair the World. Jewish Lights Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 9781580233538. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Korn, Eugene (2002). "Legal Floors and Moral Ceilings: A Jewish Understanding Of Law and Ethics" (PDF). Edah Journal. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Cordovero, Rabbi Moshe (1993). תומר דבורה [The Palm Tree of Devorah]. Targum. p. 84. ISBN 9781568710273. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Elazar, Daniel J. "Covenant as the Basis of the Jewish Political Tradition". Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- The Bahir: Illumination. Translated by Kaplan, Aryeh. Weiser Books. 2001. ISBN 9781609254933. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Green, Arthur (2004). A Guide to the Zohar. Stanford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780804749084.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chesed |