Garbled circuit

Garbled circuit is a cryptographic protocol that enables two-party secure computation in which two mistrusting parties can jointly evaluate a function over their private inputs without the presence of a trusted third party. In the garbled circuit protocol, the function has to be described as a Boolean circuit.

The history of garbled circuits is complicated. The invention of garbled circuit was credited to Andrew Yao, as Yao introduced the idea in the oral presentation of his paper[1] in FOCS'86. This was documented by Oded Goldreich in 2003.[2] The first written document about this technique was by Goldreich, Micali, and Wigderson in STOC'87.[3] The garbled circuit was first termed by Beaver, Micali, and Rogaway in STOC'90.[4] Yao's protocol solving the Yao's Millionaires' Problem was the beginning example of secure computation, yet it is not directly related to garbled circuits.

Background

Oblivious transfer

In the garbled circuit protocol, we make use of oblivious transfer. In the oblivious transfer, a string is transferred between a sender and a receiver in the following way: a sender has two strings and . The receiver chooses and the sender sends with the oblivious transfer protocol such that

- the receiver doesn't get any information about ,

- the value of is not exposed to the sender.

The oblivious transfer can be built using asymmetric cryptography like the RSA cryptosystem.

Definitions and notations

Operator is string concatenation. Operator is bit-wise XOR. k is security parameter and the length of keys. It should be greater than 80 and is usually set at 128.

Garbled circuit protocol

The protocol consists of 6 steps as follows:

- The underlying function (e.g., in the millionaires' problem, comparison function) is described as a Boolean circuit with 2-input gates. The circuit is known to both parties. This step can be done beforehand by a third-party.

- Alice garbles (encrypts) the circuit. We call Alice the garbler.

- Alice sends the garbled circuit to Bob along with her encrypted input.

- In order to calculate the circuit, Bob needs to garble his own input as well. To this end, he needs Alice to help him. Because it's only the garbler who knows how to encrypt. Finally, Bob can encrypt his input through oblivious transfer. In terms of the definition from above, Bob is the receiver and Alice the sender at this oblivious transfer.

- Bob evaluates (decrypts) the circuit and obtains the encrypted outputs. We call Bob the evaluator.

- Alice and Bob communicate to learn the output.

Circuit generation

The Boolean circuit for small functions can be generated by hand. It is conventional to make the circuit out of 2-input XOR and AND gates. It is important that the generated circuit has the minimum number of AND gates (see Free XOR optimization). There are methods that generate the optimized circuit in term of number of AND gates using logic synthesis technique.[5] The circuit for the Millionaires' Problem is a digital comparator circuit (which is a chain of full adder work as a subtractor and outputs the carry flag). The circuit of full adder can be implemented using only one AND gate and some XOR gates. This means the total number of AND gates for the circuit of the Millionaires' Problem is equal to the bit-width of inputs.

Garbling

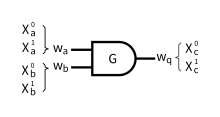

Alice (garbler) encrypts the Boolean circuit in this step to obtain a garbled circuit. Alice assigns two randomly generated strings called labels to each wire in the circuit: one for Boolean semantic 0 and one for 1. (The label is k-bit long where k the security parameter and is usually set to 128.) Next, She goes to all the gates in the circuit and replace 0 and 1 in the truth tables with the corresponding labels. The table below shows the truth table for an AND gate with two inputs: and output :

| a | b | c |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Alice replaced 0 and 1 with the corresponding labels:

| a | b | c |

|---|---|---|

She then encrypts the output entry of the truth table with the corresponding two input labels. The encrypted table is called garbled table. This is done such that one can decrypt the garbled table only if he has the correct two input labels. In the table below, is a double-key symmetric encryption in which k is the secret key and X is the value to be encrypted (see Fixed-Key Blockcipher).

| Garbled Table |

|---|

After this, Alice randomly permutes the table such that the output value cannot be determined from the row. The protocol's name, garbled, is derived from this random permutation.

Data transfer

Alice sends the computed garbled tables for all gates in the circuit to Bob. Bob needs input labels to open the garbled tables. Thus, Alice chooses the labels corresponding to her input to Bob. For example, if Alice's input is , then she sends , , , , and to Bob. Bob will not learn anything about Alice's input, , since the labels are randomly generated by Alice and they look like random strings to Bob.

Bob needs the labels corresponding to his input as well. He receives his labels through oblivious transfers for each bit of his input. For example, if Bob's input is , Bob first asks for between Alice's labels and . Through a 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer, he receives and so on. After the oblivious transfers, Alice will not learn anything about Bob's input and Bob will not learn anything about the other labels.

Evaluation

After the data transfer, Bob has the garbled tables and the input labels. He goes through all gates one by one and tries to decrypt the rows in their garbled tables. He is able to open one row for each table and retrieve the corresponding output label: , where . He continues the evaluation until he reaches to the output labels.

Revealing output

After the evaluation, Bob obtains the output label, , and Alice knows its mapping to Boolean value since she has both labels: and . Either Alice can share her information to Bob or Bob can reveal the output to Alice such that one or both of them learn the output.

Optimization

Point-and-permute

In this optimization, Alice generates a random bit, , called select bit for each wire . She then sets the first bit of label 0, to and the first bit of label 1, , to (NOT of ). She then, instead of randomly permuting, sorts the garbled table according to the inputs select bit. This way, Bob does not need to test all four rows of the table to find the correct one, since he has the input labels and can find the correct row and decrypt it with one attempt. This reduces the evaluation load by 4 times. It also does not reveal anything about the output value because the select bits are randomly generated.[6]

Row reduction

This optimization reduces the size of garbled tables from 4 rows to 3 rows. Here, instead of generating a label for the output wire of a gate randomly, Alice generates it using a function of the input labels. She generates the output labels such that the first entry of the garbled table becomes all 0 and no longer needs to be sent:[7]

Free XOR

In this optimization, Alice generates a global random (k-1)-bit value which is just known to her. During garbling for any wire , she only generates a label and computes the other label as . With this convention, the label for the output wire of the XOR gates with input wires , and output wire can be simply computed as . The proof of security for this optimization is given in the Free-XOR paper.[8]

Implication

Free XOR optimization implies an important point that the amount of data transfer (communication) and number of encryption and decryption (computation) of the garbled circuit protocol relies only on the number of AND gates in the Boolean circuit not the XOR gates. Thus, between two Boolean circuits representing the same function, the one with the smaller number of AND gates is preferred.

Fixed-key blockcipher

This method allows to efficiently garble and evaluate AND gates using fixed-key AES, instead of costly cryptographic hash function like SHA-2. In this garbling scheme which is compatible with the Free XOR and Row Reduction techniques, the output key is encrypted with the input token and using the encryption function , where , is a fixed-key block cipher (e.g., instantiated with AES), and is a unique-per-gate number (e.g., gate identifier) called tweak.[9]

Half And

This optimization reduce the size of garbled table for AND gates from 3 row in Row Reduction to 2 rows. It is shown that this is the theoretical minimum for the number of rows in the garbled table, for a certain class of garbling techniques.[10]

See also

- Cryptography

- RSA

- Secure multi-party computation

- Yao's Millionaires' Problem

References

- Yao, Andrew Chi-Chih (1986). How to generate and exchange secrets. Foundations of Computer Science, 1986., 27th Annual Symposium on. pp. 162–167. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1986.25. ISBN 978-0-8186-0740-0.

- Goldreich, Oded (2003). "Cryptography and Cryptographic Protocols". Distributed Computing - Papers in Celebration of the 20th Anniversary of PODC. 16 (2–3): 177–199. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.117.3618. doi:10.1007/s00446-002-0077-1.

- Goldreich, Oded; Micali, Silvio; Wigderson, Avi (1987). How to play ANY mental game. Proceeding STOC '87 Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 218–229. doi:10.1145/28395.28420. ISBN 978-0897912211.

- Beaver, Donald; Micali, Silvio; Rogaway, Phillip (1990). The Round Complexity of Secure Protocols. Proceeding STOC '90 Proceedings of the Twenty-second Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 503–513. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.697.1624. doi:10.1145/100216.100287. ISBN 978-0897913614.

- Songhori, Ebrahim M; Hussain, Siam U; Sadeghi, Ahmad-Reza; Schneider, Thomas; Koushanfar, Farinaz (2015). TinyGarble: Highly compressed and scalable sequential garbled circuits. Security and Privacy (SP), 2015 IEEE Symposium on. pp. 411–428. doi:10.1109/SP.2015.32. ISBN 978-1-4673-6949-7.

- Beaver, Donald; Micali, Silvio; Rogaway, Phillip (1990). The round complexity of secure protocols. Proceedings of the Twenty-second Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 503–513. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.697.1624. doi:10.1145/100216.100287. ISBN 978-0897913614.

- Naor, Moni; Pinkas, Benny; Sumner, Reuban (1999). Privacy preserving auctions and mechanism design. Proceedings of the 1st ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce. pp. 129–139. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.17.7459. doi:10.1145/336992.337028. ISBN 978-1581131765.

- Kolesnikov, Vladimir; Schneider, Thomas (2008). Improved garbled circuit: Free XOR gates and applications. International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 5126. pp. 486–498. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.160.5268. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70583-3_40. ISBN 978-3-540-70582-6.

- Bellare, Mihir; Hoang, Viet Tung; Keelveedhi, Sriram; Rogaway, Phillip (2013). Efficient garbling from a fixed-key blockcipher. Security and Privacy (SP), 2013 IEEE Symposium on. pp. 478–492. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.299.2755. doi:10.1109/SP.2013.39. ISBN 978-0-7695-4977-4.

- Zahur, Samee; Rosulek, Mike; Evans, David (2015). Two halves make a whole (PDF).

Further reading

- "Yao's Garbled Circuit" (PDF). CS598. illinois.edu. Retrieved 18 October 2016.