Gaping Gill

Gaping Gill (also known as Gaping Ghyll) is a natural cave in North Yorkshire, England. It is one of the unmistakable landmarks on the southern slopes of Ingleborough – a 98-metre (322 ft) deep pothole with the stream Fell Beck flowing into it.[3] After falling through one of the largest known underground chambers in Britain, the water disappears into the bouldery floor and eventually resurges adjacent to Ingleborough Cave.[1][4]

| Gaping Gill | |

|---|---|

Entrance shaft viewed from the Main Chamber | |

| |

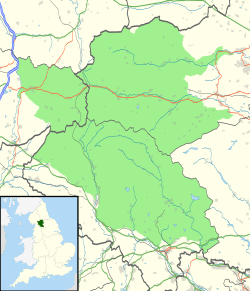

| Location | Ingleborough, North Yorkshire, England |

| OS grid | SD 75117270[1] |

| Coordinates | 54°08′58″N 2°22′57″W |

| Depth | 192 metres (630 ft)[2] |

| Length | 21 kilometres (13 mi) (including Ingleborough Cave)[2] |

| Geology | Carboniferous limestone |

| Entrances | 21[1] |

| Access | Ingleborough Estate Office |

| BRAC grade | 4 |

The shaft was the deepest known in Britain, until Titan in Derbyshire was discovered in 1999.[5] Gaping Gill still retains the records for the highest unbroken waterfall in England and the largest underground chamber naturally open to the surface.

Features

Due to the number of entrances which connect into the cave, many different routes through and around the system are possible. Other entrances include Jib Tunnel, Disappointment Pot, Stream Passage Pot, Bar Pot, Hensler's Pot, Corky's Pot, Rat Hole, and Flood Entrance Pot.

The Bradford Pothole Club around Whitsun May Bank Holiday,[6] and the Craven Pothole Club around August Bank Holiday,[7] each set up a winch above the shaft to provide a ride to the bottom and back out again for any member of the public who pays a fee.

A detailed 3D model of the chamber has been created using an industrial laser rangefinder which showed that its volume is comparable to the size of York Minster.[8][9]

History of exploration

Descents

The first recorded attempted descent was by John Birkbeck in 1842 who reached a ledge approximately 55 metres (180 ft) down the shaft which bears his name.[10] The first complete descent was achieved by Édouard-Alfred Martel in 1895.

Hensler's Crawl and Master Cave

On 25 July 1937[11] Eric Hensler (1907–1991) explored a low passage leeding off of Booth-Parsons crawl, finding it to be unexplored. This was later named Hensler's Crawl, and was also found to lead into Hensler's Master Cave.[12]

Since 1937

In 1983 members of the Cave Diving Group made the underwater connection into Ingleborough Cave.

An extreme rock-climb (graded E3, 5c) is possible up the main shaft which requires very dry conditions. It was first pioneered in 1972 with ten points of aid. The first free ascent was made in 1988.[13]

References

- Gardner, John. "Gaping Gill – A list of entrances". Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Dixon, Kevin (August–September 2016). "Gaping Gill: The Survey". Descent (251): 22–27.

- Cordingley, John (2002). "The True Depth of Gaping Gill". Cave and Karst Science. 29 (3): 136.

- "Gaping Gill". Bradford Pothole Club. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "Battle of Titan's proportions after news of biggest cave". grough. 7 November 2006. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- "Gaping Gill". Bradford Pothole Club. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Gaping Gill". Craven Pothole Club. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Laser scanner provides first 3D view of legendary Dales Cavern". Yorkshire Post. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "MDL Creates First Complete 3D Model of Gaping Gill". MDL Laser Systems. 4 September 2008. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Marshal, Des; Rust, Donald (1997). Selected Caves of Britain and Ireland. p. 47. ISBN 1-871890-43-8.

- "MCRA Logbooks Browser". www.mcra.org.uk. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "British Caving Library". caving-library.org.uk. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Eastwood, Paul (1989). "Gee Gee Rider – first free ascent". NPC Newsletter 23, January 1989. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

Sources

- Beck, Howard M. (1984). Gaping Gill: 150 years of exploration. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-1552-6.

- Brook, D.; et al. Northern Caves 2 – the Three Peaks. Dalesman Press. ISBN 1-85568-033-5.

- Farr, Martyn. The Darkness Beckons: History and Development of Cave Diving. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-906371-87-2.

- Mason, E. J. (1977). Caves and Caving in Britain. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-6195-6.

- Dixon, Kevin (2015). Gaping Gill. Geospatial3D. ISBN 978-0-9933481-0-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gaping Gill. |