Game design document

A game design document (often abbreviated GDD) is a highly descriptive living software design document of the design for a video game.[1][2][3][4] A GDD is created and edited by the development team and it is primarily used in the video game industry to organize efforts within a development team. The document is created by the development team as result of collaboration between their designers, artists and programmers as a guiding vision which is used throughout the game development process. When a game is commissioned by a game publisher to the development team, the document must be created by the development team and it is often attached to the agreement between publisher and developer; the developer has to adhere to the GDD during game development process.

| Part of a series on the: |

| Video game industry |

|---|

|

Activities/jobs

|

|

|

Types |

|

Related |

Life cycle

Game developers may produce the game design document in the pre-production stage of game development—prior to or after a pitch.[5] Before a pitch, the document may be conceptual and incomplete. Once the project has been approved, the document is expanded by the developer to a level where it can successfully guide the development team.[1][6] Because of the dynamic environment of game development, the document is often changed, revised and expanded as development progresses and changes in scope and direction are explored. As such, a game design document is often referred to as a living document, that is, a piece of work which is continuously improved upon throughout the implementation of the project, sometimes as often as daily.[2][7][8][9] A document may start off with only the basic concept outlines and become a complete, detailed list of every game aspect by the end of the project.

Content

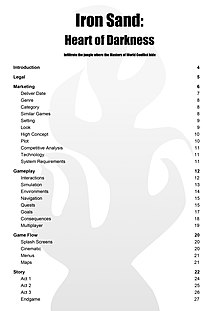

A game design document may be made of text, images, diagrams, concept art, or any applicable media to better illustrate design decisions. Some design documents may include functional prototypes or a chosen game engine for some sections of the game.

Although considered a requirement by many companies, a GDD has no set industry standard form. For example, developers may choose to keep the document as a word processed document, or as an online collaboration tool.

Structure

The purpose of a game design document is to unambiguously describe the game's selling points, target audience, gameplay, art, level design, story, characters, UI, assets, etc.[10][11] In short, every game part requiring development should be included by the developer in enough detail for the respective developers to implement the said part.[12] The document is purposely sectioned and divided in a way that game developers can refer to and maintain the relevant parts.

The majority of video games should require an inclusion or variation of the following sections:[13][14]

- Story

- Characters

- Level/environment design

- Gameplay

- Art

- Sound and Music

- User Interface, Game Controls

- Accessibility

- Monetization

This list is by no means exhaustive or applicable to every game. Some of these sections might not appear in the GDD itself but instead would appear in supplemental documents.

Notes

- Oxland 2004, p. 240

- Brathwaite, Schreiber 2009, p. 14

- Bates 2004, p. 276.

- Bethke 2003, pp. 101–102

- Moore, Novak 2010, p. 70

- Bethke 2003, p. 103

- Oxland 2004, pp. 241–242, 185

- Moore, Novak 2010, p. 73

- Bethke 2003, p. 104

- Bates 2004, pp. 276–291

- Bethke 2003, p. 102

- Bethke 2003, p. 105

- Oxland 2004, pp. 274–186

- Adams, Rollings 2003, pp. 569–570, 574–576

References

- Adams, Ernest; Rollings, Andrew (2003). Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on game design. New Riders Publishing. ISBN 1-59273-001-9.

- Bates, Bob (2004). Game Design (2nd ed.). Thomson Course Technology. ISBN 1-59200-493-8.

- Bethke, Erik (2003). Game development and production. Texas: Wordware Publishing, Inc. ISBN 1-55622-951-8.

- Brathwaite, Brenda; Schreiber, Ian (2009). Challenges for Game Designers. Charles River Media. ISBN 1-58450-580-X.

- Moore, Michael E.; Novak, Jeannie (2010). Game Industry Career Guide. Delmar: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4283-7647-2.

- Oxland, Kevin (2004). Gameplay and design. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-321-20467-0.

External links

- Anatomy of a GDD by Tim Ryan on Gamasutra

- Game specifications by Tom Sloper on Sloperama