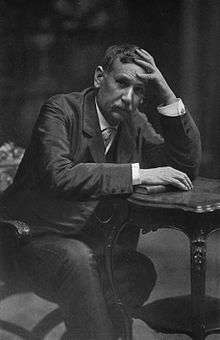

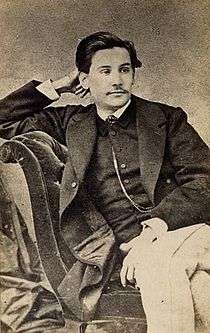

Benito Pérez Galdós

Benito Pérez Galdós (May 10, 1843 – January 4, 1920) was a Spanish realist novelist. He was the leading literary figure in 19th-century Spain, and some scholars consider him second only to Miguel de Cervantes in stature as a Spanish novelist.[1][2]

Benito Pérez Galdós | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Benito María de los Dolores Pérez Galdós May 10, 1843 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain |

| Died | January 4, 1920 (aged 76) Madrid, Spain |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, politician |

Galdós was a prolific writer, publishing 31 novels, 46 Episodios Nacionales (National Episodes), 23 plays, and the equivalent of 20 volumes of shorter fiction, journalism and other writings.[1] He remains popular in Spain, and is considered as equal to Dickens, Balzac and Tolstoy.[1] As recently as 1950, few of Galdós's works were available translated to English, although he has slowly become popular in the Anglophone world.

While his plays are generally considered to be less successful than his novels, Realidad (1892) is important in the history of realism in the Spanish theatre.

The Galdós museum in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria features a portrait of the writer by Joaquín Sorolla.

Career as a writer

By 1865, he was publishing articles in La Nación on literature, art, music, and politics and it was clear that he was not going to pursue a legal career. His first attempt at a literary career came in 1867, when a didactic historical verse drama was rejected.[3] His next venture into the theatre did not take place until 1892.

He had already become enthusiastic about the novels of Charles Dickens and, in 1868, his translation of Pickwick Papers introduced his work to the Spanish public. The previous year, he had visited Paris and had begun to read the works of Balzac. In 1870, he was appointed editor of La Revista de España and began to express his opinions on a wide range of diverse topics such as history, culture, politics, art, music and literature. Between 1867 and 1868, he wrote what would be his first novel, La Fontana de Oro, a historical work set in the period 1820–1823. With the help of money from his sister-in-law, it was published privately in 1870. Critical reaction was slow to gain momentum but it was eventually hailed as the beginning of a new phase in Spanish fiction, and was highly praised for its literary quality as well as for its social and moral purpose.[3]

National Episodes

He next developed the outline of a major project, the Episodios Nacionales: a series of historical novels outlining the major events in Spanish history from the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 to his own times. The ostensible aim of this project was to regenerate Spain through the awakening of a new sense of national identity. The first episode was called Trafalgar and appeared in 1873. Successive episodes appeared in fits and starts until the forty-sixth and final novel, Cánovas, appeared in 1912. Every so often, Galdós seemed to grow tired of this project and stated that he would not write another episode. However, the public bought them avidly, despite the criticism that was levelled at his other works, and they remained the basis of his contemporary reputation and income. He conducted an enormous amount of research in the writing of these stories because official reports, newspaper accounts and histories were often rigidly partisan. To achieve balance and a wider perspective, Galdós sought out survivors and eyewitnesses to the actual events – such as an old man who had been a cabin boy aboard the ship Santísima Trinidad at Trafalgar, who became the central figure of that book. Galdós is often critical of the official versions of the events he describes and often ran into problems with the Catholic Church, then a dominant force in Spanish cultural life.

Other novels

His other novels were classified into the groups by José Montesinos:[4]

- The early works from La Fontana de Oro up to La familia de León Roch (1878). The best known of these is probably Doña Perfecta (1876), which describes the impact made by the arrival of a young radical on a stiflingly clerical town. In Marianela (1878) a young man regains his eyesight after a life of blindness and rejects his best friend Marianela for her ugliness.

- The Novelas españolas contemporáneas, from La desheredada (1881) to Angel Guerra (1891), a loosely related series of 22 novels which are the author’s major claim to literary distinction, including his masterpiece Fortunata y Jacinta (1886–87). They are bound together by the device of recurring characters, borrowed from Balzac’s La Comédie humaine. Fortunata y Jacinta is almost as long as War and Peace. It concerns the fortunes of four characters: a young man-about-town, his wife, his lower-class mistress, and her husband. The character of Fortunata is based on a real girl whom Galdós first saw in a tenement building in Madrid, drinking a raw egg – which is the way in which the fictional characters come to meet.

- The later novels of psychological investigation, many of which are in dialogue form.

Influences and characteristics

Galdós was an enthusiastic traveller. His novels display a detailed knowledge of not only Madrid but many other cities, towns and villages of Spain – such as Toledo in Angel Guerra. He visited Great Britain on many occasions, his first trip being in 1883. The descriptions of the various districts and low-life characters that he encountered in Madrid, particularly in Fortunata y Jacinta, are similar to the approaches of Dickens and the French Realist novelists such as Balzac. Galdós also shows a Balzacian interest in technology and crafts, for example the lengthy descriptions of the ropery in La desheredada or the detailed accounts of how the heroine of La de Bringas (1884) embroiders her pictures out of hair.

He was also inspired by Émile Zola and Naturalism in which, under the influence of the deterministic philosophy of Hippolyte Taine, writers strove to show how their characters were forged by the interaction of heredity, environment and social conditions – race, milieu, et moment. In addition, these writers were keen to suggest that their works were scientific dissections of society. This set of influences is, perhaps, at its clearest in Lo prohibido (1884–85),[5] which is also noteworthy for being told in the first person by an unreliable narrator who, in addition, dies during the course of the work – it pre-dates similar experiments by André Gide such as L'immoraliste.

Another influence came from the philosophy of Karl Christian Friedrich Krause, which became influential in Spain mainly due to the influence of the famous educationalist Francisco Giner de los Ríos. The clearest example of this influence on Galdós is in his novel El Amigo Manso (1882). However, it is also clear that the mystical tendencies of krausismo led to his interest in insanity and the strange wisdom that can sometimes be shown by those people who appear to be mad. This becomes a theme of great importance in the works of Galdós from Fortunata y Jacinta onwards, for example in Miau (1888) and his final novel La razón de la sinrazón.

All through his literary career, Galdós incurred the wrath of the Catholic press. He attacked what he saw as abuses of entrenched and dogmatic religious power rather than religious faith or Christianity per se. In fact, the need for faith is a very important feature in many of his novels and there are many sympathetic portraits of priests and nuns.[3]

Return to the theatre

His first mature play was Realidad, an adaptation of his novel of the same name, which had been written in dialogue. Galdós was attracted to the idea of making direct contact with his public and seeing and hearing their reactions. Rehearsals began in February 1892. The theatre was packed on the opening night and received the play enthusiastically. Galdós took about 15 curtain calls. However, although the audience reception was good, the play did not receive universal critical acclaim because of its realistic dialogue which did not accord with the general theatrical language of the time, the setting of a scene in the boudoir of a courtesan, and the un-Spanish attitude towards a wife’s adultery. The Catholic press did not attend the performance but this did not prevent them from denouncing the author as a perverse and wicked influence. The play ran for twenty nights.[3]

In 1901, his play Electra caused a storm of outrage and floods of equally hyperbolic enthusiasm. As in many of his works, Galdós targeted clericalism and the inhuman fanaticism and superstition that can accompany it. The performance was interrupted by audience reaction and the author had to take many curtain calls. After the third night, the conservative and clerical parties organised a demonstration outside the theatre. The police moved in and arrested two members of a workers’ organization who had reacted against the demonstration. Several people were wounded as a result of the clash and, the next day, the newspapers were divided between liberal support for the play and Catholic/conservative condemnation. Over one hundred performances were given in Madrid alone and the play was also performed in the provinces. In 1934, 33 years later, a revival in Madrid produced much the same degree of uproar and outrage.[3]

Later life and political involvement

Despite his attacks on the forces of conservatism, Galdós had only shown a weak interest in being directly involved in politics. In 1886 the Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta appointed him as the (absent) deputy for the town and district of Guayama, Puerto Rico at the Madrid parliament; he never visited the place, but had a representative inform him of the status of the area, and felt a duty to represent its inhabitants appropriately. This appointment lasted for five years and mainly seems to have given him the chance to observe the conduct of politics at first hand, which informs scenes in some of his novels.

By 1907, however, there was no sign of national regeneration and the government of the day was making no attempt to control or limit the powers of the Catholic Church. At the age of 64, he re-entered the political arena as a Republican deputy. He seems to have undertaken the task of uniting the anti-monarchic groups, which included Democrats, Republicans, liberals and socialists. He even approached the Marxist leader Pablo Iglesias and persuaded him to join a new organisation called La Conjunción Republicano-socialista, with Galdós as its titular head.[3]

However, by 1912, Galdós was growing disillusioned with the way that the personal ambitions of his fellow Republicans conflicted with achieving genuine political change and it was becoming clear that the coalition of anti-monarchic groups was unable to exercise any great influence over developments. He began to fade from the scene of active political involvement. In 1914, he was the Republican candidate for Las Palmas, but this was more of a local tribute to him. In 1918, he joined in a protest with Miguel de Unamuno and Mariano de Cavia against the encroaching censorship and authoritarianism coming from the putatively constitutional monarch.[6] He had been blind since 1912, was in financial difficulties and increasingly troubled by illness.[3]

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature for five years, 1912–16, which would both have increased his prestige outside Spain and improved his financial status, but neither was successful.[7] Among those who nominated Pérez Galdós was the 1904 winner José Echegaray.[8] A national subscription scheme was set up to raise money to help Pérez Galdós, to which the King and his Prime Minister Romanones were the first to subscribe. The activities of the Catholic press, which sneered at the writer as a blind beggar, along with the outbreak of World War I, led to the scheme being closed in 1916 with the money raised being less than half what would be required to clear his debts and set up a pension. In that same year, however, the Ministry of Public Instruction appointed him to take charge of the arrangements for the Cervantes tercentenary, for a stipend of 1000 pesetas per month. Although the event never took place, the stipend continued for the rest of Galdós’s life.[3]

In 1897, Pérez Galdós had been elected to the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy). After becoming blind he continued to dictate his books for the rest of his life. Pérez Galdós died at the age of 76. Shortly before his death, a statue in his honour was unveiled in the Parque del Buen Retiro, the most popular park in Madrid, financed solely by public donations.

Film adaptations

His novels have yielded many cinematic adaptations: Beauty in Chains (Doña Perfecta) was directed by Elsie Jane Wilson in 1918; Viridiana (1961), by Luis Buñuel, is based upon Halma; Buñuel also adapted Nazarín (1959) and Tristana (1970); La Duda was filmed in 1972 by Rafael Gil; El Abuelo (1998) (The Grandfather), by José Luis Garci, was internationally released a year later; it previously had been adapted as the Argentine film, El Abuelo (1954). In 2018, Sri Lankan director, Bennett Rathnayke directed the film Nela.[9]

Works

Early Novels

- La Sombra (1870)

- La Fontana de Oro (1870)

- El Audaz (1871)

- Doña Perfecta (1876)

- Gloria (1877)

- La Familia de León Roch (1878)

- Marianela (1878)

Novelas Españolas Contemporáneas

- La Desheredada (1881)

- El Doctor Centeno (1883)

- Tormento (1884)[10]

- La de Bringas (1884)

- El Amigo Manso (1882)

- Lo Prohibido (1884–85)

- Fortunata y Jacinta (1886–87)

- Celín, Tropiquillos y Theros (1887)

- Miau (1888)

- La Incógnita (1889)

- Torquemada en la Hoguera (1889)

- Realidad (1889)

- Ángel Guerra (1890–91)

Later Novels

- Tristana (1892)

- La Loca de la Casa (1892)

- Torquemada en la Cruz (1893)

- Torquemada en el Purgatorio (1894)

- Torquemada y San Pedro (1895)

- Nazarín (1895)

- Halma (1895)[11]

- Misericordia (1897)

- El Abuelo (1897)

- La Estafeta Romántica (1899)

- Casandra (1905)

- El Caballero Encantado (1909)

- La Razón de la Sinrazón (1909)

Episodios Nacionales

Plays

- Quien Mal Hace, Bien no Espere (1861, lost)

- La Expulsión de los Moriscos (1865, lost)

- Un Joven de Provecho (1867?, published in 1936)

- Realidad (1892)

- La Loca de la Casa (1893)[12]

- Gerona (1893)

- La de San Quintín (1894)

- Los Condenados (1894)

- Voluntad (1895)

- La Fiera (1896)

- Doña Perfecta (1896)

- Electra (1901)[13]

- Alma y Vida (1902)

- Mariucha (1903)

- El Abuelo (1904)

- Amor y Ciencia (1905)

- Barbara (1905)

- Zaragoza (1908)

- Pedro Minio (1908)

- Casandra (1910)

- Celia en los Infiernos (1913)

- Alceste (1914)

- Sor Simona (1915)

- El Tacaño Salomón (1916)

- Santa Juana de Castilla (1918)

- Antón Caballero (1921, unfinished)

Miscellaneous

- Crónicas de Portugal (1890)

- Discurso de Ingreso en la Real Academia Española (1897)

- Memoranda, Artículos y Cuentos (1906)

- La Novela en el Tranvía

- Política Española I (1923)

- Política Española II (1923)

- Arte y Crítica (1923)

- Fisonomías Sociales (1923)

- Nuestro Teatro (1923)

- Cronicón 1883 a 1886 (1924)

- Toledo. Su historia y su Leyenda (1927)

- Viajes y Fantasías (1929)

- Memorias (1930)

Notes

- Davies, Rhian. Teaching European Literature and Culture with Communication and Information Technologies: The Pérez Galdós Editions Project

- "...considered by some critics the greatest Spanish novelist since Cervantes, often compared to Balzac, Dickens, and Tolstoy." Encyclopædia Britannica 15th Edition (1985)

- Berkowitz

- Montesinos "Galdos"

- Montesinos intro to Lo prohibido p. 21

- Berkowitz, H. Chonon (October 1940). "Unamuno's Relations with Galdós". Hispanic Review. 8 (4): 330.

- "Benito Pérez Galdós", Nomination Database, Nobelprize.org.

- "José Echegaray y Eizaguirre", Nomination Database, Nobelprize.org.

- "Bennett brought Nela to silver screen". Sarasaviya. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Wood, Gareth J. (2014). "Galdós, Shakespeare, and What to Make of Tormento," The Modern Language Review, Vol. 109, No. 2, pp. 392–416.

- Brown, Daniel (2011). "Mystical Winds, Traditions, and Contradictions in Galdós's 'Halma'," Pacific Coast Philology, Vol. 46, pp. 46–64.

- Copeland, Eva Maria (2012). "Empire, Nation, and the indiano in Galdós's 'Tormento' and 'La Loca de la Casa'," Hispanic Review, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 221–242.

- Ellis, Havelock (1901). "'Electra' and the Progressive Movement in Spain," The Critic, Vol. 39, pp. 213–217.

References

- Montesinos, Jose (1971). Intro to Lo Prohibido. Madrid: Editorial Castalia. ISBN 84-7039-106-2.

- Berkowitz, H, Chonon (1948). Perez Galdos, Spanish Liberal Crusader. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Montesinos, Jose (1968–71). Galdos. Madrid.

Further reading

- Alfieri, J.J. (1968). "Galdós Revaluated (sic)" Books Abroad, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 225–226.

- Bishop, William Henry (1917). "Benito Pérez Galdós." In: The Warner Library. New York: Knickerbocker Press, pp. 6153–6163.

- Chamberlin, Vernon A. (1964). "Galdós' Use of Yellow in Character Delineation," PMLA, Vol. 79, No. 1, pp. 158–163.

- Ellis, Havelock (1906). "The Spirit of Present Day Spain," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 98, pp. 757–765.

- Geddes Jr., James (1910). "Introduction." In: Marianela. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co., pp. iii–xvi.

- Glascock, C.C. (1923). "Spánish Novelist: Benito Perez Galdos," Texas Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 158–177.

- Gómez Martínez, José Luis (1983). "Galdós y el Krausismo español" Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 55–79.

- Huntington, Archer M. (1897). "Perez Galdós in the Spanish Academy," The Bookman, Vol. V, pp. 220–222.

- Karimi, Kian-Harald (2007): Jenseits von altem Gott und ‘Neuem Menschen’. Präsenz und Entzug des Göttlichen im Diskurs der spanischen Restaurationsepoche. Frankf./M.: Vervuert. ISBN 3-86527-313-0

- Keniston, Hayward (1920). "Galdós, Interpreter of Life," Hispania, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 203–206.

- Madariaga, Salvador de (1920). "The Genius of Spain," Contemporary Review, Vol. 117, pp. 508–516.

- Miller, W. (1901). "The Novels of Pérez Galdós," The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 291, pp. 217–228.

- Pattison, Walter T. (1954). Benito Pérez Galdós and the Creative Process. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ridao Carlini, Inma (2018): Rich and Poor in Nineteenth-Century Spain: A Critique of Liberal Society in the Later Novels of Benito Pérez Galdós. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-85566-330-5

- Waldeck, R.W. (1904). "Benito Pérez Galdós, Novelist, Dramatist and Reformer" The Critic, Vol. 45, No. 5, pp. 447–449.

- Warshaw, J. (1929). "Galdós's Apprenticeship in the Drama," Modern Language Notes, Vol. 44, No. 7, pp. 459–463.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benito Pérez Galdós. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Pérez Galdós, Benito. |

- The Pérez Galdós Editions Project

- Works by Benito Pérez Galdós at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benito Pérez Galdós at Internet Archive

- Works by Benito Pérez Galdós at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Benito Pérez Galdós on IMDb

- Galdós site, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish)

- The Galdós House Museum. The Museum is set up in Pérez Galdós' birthplace in Gran Canaria. (in Spanish)

- Benito Pérez Galdós- Webpage dedicated to Galdosian Studies

- Benito Pérez Galdós Published in The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature (2004)