Furius Dionysius Filocalus

Furius Dionysius Filocalus or Filocalus was a Roman calligrapher and stone engraver, specialized in epigraphic texts, who was active in the second half of the fourth century.

Chronography of 354

One of his most noteworthy works is the "Chronography of 354", also known as the "Calendar of 354", of which the original has been lost. It is the oldest known Christian calendar, with the first known reference to the celebration of the Christmas, although it also incorporates Roman festivities. The most complete copy conserved today is a manuscript of the 17th century which is kept in the Barberini collection. This is the reproduction of a "Codex Luxemburgensis" of the Carolingian dynasty, which was lost in the seventeenth century.

The "chronography" was commissioned by a wealthy Roman Christian, known as Valentinus, to whom it was dedicated. The original manuscript miniatures were also probably the work of Filocalus.

The pope's official engraver

Filocalus was the official engraver of Pope Damasus (304 - 384), and described himself as "Damasi pappae cultor atque amator" ("admirer and personal friend of Pope Damasus").[1] The archaeologist Giovanni Battista de Rossi suggests that his inscriptions were reserved for the cult of the martyrs. It is not known for certain whether these inscriptions were drawn and engraved by Filocalus, or only drawn by him, but the first hypothesis seems to be correct. The precision of the cut of the stone and the organic regularity between the letters suggest the work of a master who works based on a sketch, rather than a craftsman copying an elaborate drawing.[2]

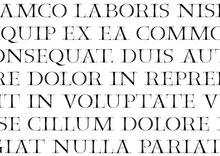

For these inscriptions, called the Epigrammata Damasiana,[3] Filocalus created an original letterform that is known as filocalian letter[2] or philocalian script.[4] Its main features are its thin and wavy ornamental serifs. It also has a strong contrast, with thin horizontal strokes and with vertical strokes which are thick in the downward direction and thin in the ascendant. It also presents vertically squashed forms; especially in the letters C, D, G, H, M, N, O, Q, R and T, which are wider than they are tall. The rounded letters (D, G, O, Q) all have an oblique axis.[5]

Three fourth-century fragments of the filocalian letter engraved in stone are known, which seem to have been signed in the same way, with the inscription Furius Dionysius Filocalus scribsit.[2] These fragments were part of the transcription of a series of poems that Pope Damasus I had written in honor of the martyrs, and which were employed to decorate their tombs.[2] This typeface had a great influence on the engravers of the time, who copied its style extensively, and of which a great number of examples are known.

Legacy

The first Tuscan-style metal sorts appeared around 1887. They were created by British type designer Vincent Figgins, who named his typeface 4-lines Pica Ornamented no. 2.[6] His letters were inspired by the ornamental designs of Fournier, but the oldest ancestor for his ornamental serfis is the filocalian letter.[7] Tuscan style was widely popular during the Victorian Times, and it's still used nowadays.

Notes and references

- Salzman, Michele Renée. "Filocalus, Furius Dionysius". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill’s New Pauly. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Gray, Nicolette (1956). "The Filocalian Letter". Papers of the British School at Rome. 24: 5–13. doi:10.1017/S0068246200006747.

- Glock, Andreas. "Epigrammata Damasiana". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill’s New Pauly. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Trout, Dennis (2015). "Furius Dionysius Filocalus and Philocalian Script". Damasus of Rome: The Epigraphic Poetry : Introduction, Texts, Translations, and Commentary. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–52. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Petrucci, Armando (2011). Libros, escrituras y bibliotecas (in Spanish). University of Salamanca. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Baines, Phil; Haslam, Andrew (2005). "Nineteenth century vernacular sources". Type & Typography. Lawrence King Publishing. p. 69. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Clayton, Ewan (2013). The Golden Thread: The Story of Writing. Atlantic Books Ltd. Retrieved 4 January 2017.