Functional integration (neurobiology)

Functional integration is the study of how brain regions work together to process information and effect responses. Though functional integration frequently relies on anatomic knowledge of the connections between brain areas, the emphasis is on how large clusters of neurons – numbering in the thousands or millions – fire together under various stimuli. The large datasets required for such a whole-scale picture of brain function have motivated the development of several novel and general methods for the statistical analysis of interdependence, such as dynamic causal modelling and statistical linear parametric mapping. These datasets are typically gathered in human subjects by non-invasive methods such as EEG/MEG, fMRI, or PET. The results can be of clinical value by helping to identify the regions responsible for psychiatric disorders, as well as to assess how different activities or lifestyles affect the functioning of the brain.

Imaging techniques

A study's choice of imaging modality depends on the desired spatial and temporal resolution. fMRI and PET offer relatively high spatial resolution, with voxel dimensions on the order of a few millimeters,[1] but their relatively low sampling rate hinders the observation of rapid and transient interactions between distant regions of the brain. These temporal limitations are overcome by MEG, but at the cost of only detecting signals from much larger clusters of neurons.[2]

fMRI

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a form of MRI that is most frequently used to take advantage of a difference in magnetism between oxy- and deoxyhemoglobin to assess blood flow to different parts of the brain. Typical sampling rates for fMRI images are in the tenths of seconds.[3]

MEG

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is an imaging modality that uses very sensitive magnetometers to measure the magnetic fields resulting from ionic currents flowing through neurons in the brain. High-quality MEG machines allow for sub-millisecond sampling rates.[2]

PET

PET works by introducing a radiolabeled biologically active molecule. The choice of molecule dictates what is visualized: by using a radiolabeled analog of glucose, for example, one can obtain an image whose intensity distribution indicates metabolic activity. PET scanners offer sampling rates in the tenths of seconds.[4]

Multimodal imaging

Multimodal imaging frequently consists of the coupling of an electrophysiologic measurement technique, such as EEG or MEG, with a hemodynamic one such as fMRI or PET. While the intention is to use the strengths and limitations of each to complement the other, current approaches suffer from experimental limitations.[5] Some previous work has focused on attempting to use the high spatial resolution of fMRI to determine the (spatial) origin of EEG/MEG signals, so that in future work this spatial information could be extracted from a unimodal EEG/MEG signal. While some studies have seen success in correlating signal origins between modalities to within a few millimeters, the results have not been uniformly positive. Another current limitation is the actual experimental setup: taking measurements using both modalities at once yields inferior signals, but the alternative of measuring each modality separately is confounded by trial-to-trial variability.[5]

Modes of analysis

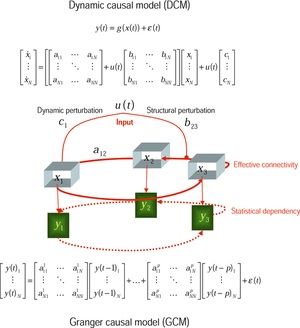

In functional integration, there is a distinction drawn between functional connectivity, and effective connectivity. Two brain regions are said to be functionally connected if there is a high correlation between the times that the two are firing, though this does not imply causality. Effective connectivity, on the other hand, is a description of the causal relationship between various brain regions.[6]

While statistical assessment of the functional connectivity of multiple brain regions is non-trivial, determining the causality of which brain regions influence which to fire is much thornier, and requires solutions to ill-posed optimization problems.[7]

Dynamic causal modelling

Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) is a Bayesian method for deducing the structure of a neural system based on the observed hemodynamic (fMRI) or electrophysiologic (EEG/MEG) signal. The first step is to make a prediction as to the relationships between the brain regions of interest, and formulate a system of ordinary differential equations describing the causal relationship between them, although many parameters (and relationships) will be initially unknown. Using previous results on how neural activity is known to translate into fMRI or EEG signals,[8] one can take the measured signal and determine the likelihood that model parameters have particular values. The elucidated model can then be used to predict relationships between the considered brain regions under different conditions.[9] A key factor to consider during the design of neuroimaging experiments involving DCM is the relationship between the timing of tasks or stimuli presented to the subject and the ability of DCM to determine the underlying relationships between brain regions, which is partially determined by the temporal resolution of the imaging modality in use.[10]

Statistical parametric mapping

Statistical parametric mapping (SPM) is a method for determining whether the activation of a particular brain region changes between experimental conditions, stimuli, or over time. The essential idea is simple, and consists of two major steps: first, one performs a univariate statistical test on each individual voxel between each experimental condition.[11] Second, one analyzes the clustering of the voxels that show statistically significant differences, and determines which brain regions exhibit different levels of activation under different experimental conditions.

There is great flexibility in the choice of statistical test (and thus the questions that an experiment can be designed to answer), and common choices include the Student's t test or linear regression. An important consideration with SPM, however, is that the large number of comparisons requires one to control the false positive rate with a more stringent significance threshold. This can be done either by modifying the initial statistical test to decrease the α value so as to make it harder for a particular voxel to exhibit a significant difference (e.g., Bonferroni correction), or by modifying the clustering analysis in the second step by only considering a brain region's activation to be significant if it contains a certain number of voxels that exhibit a statistical difference (see random field theory).[11]

Voxel-based morphometry

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) is a method that allows one to measure brain tissue composition differences between subjects. To do so, one must first register all images to a standard coordinate system, by mapping them to a reference image. This is done by use of an affine transformation that minimizes the sum-of-squares intensity difference between the experimental image and the reference. Once this is done, the proportion of grey or white matter in a voxel can be determined by intensity. This allows one to compare the tissue composition of corresponding brain regions between different subjects.[12]

Applications

The ability to visualize whole-brain activity is frequently used in comparing brain function during various sorts of tasks or tests of skill, as well as in comparing brain structure and function between different groups of people.

Changes in resting-state brain activation

Many previous fMRI studies have seen that spontaneous activation of functionally connected brain regions occurs during the resting state, even in the absence of any sort of stimulation or activity. Human subjects presented with a visual learning task exhibit changes in functional connectivity in the resting state for up to 24 hours and dynamic functional connectivity studies have even shown changes in functional connectivity during a single scan. By taking fMRI scans of subjects before and after the learning task, as well as on the following day, it was shown that the activity had caused a resting-state change in hippocampal activity. Dynamic causal modeling revealed that the hippocampus also exhibited a new level of effective connectivity with the striatum, though there was no learning-related change in any visual area.[13] Combining fMRI with DCM on subjects performing a learning task allows one to delineate which brain systems are involved in various sorts of learning, whether implicit or explicit, and document for long these tasks lead to changes in resting-state brain activation.

IQ estimation

Voxel-based morphometric measurements of grey matter localization in the brain can be used to predict components of IQ. A set of 35 teenagers were tested for IQ and were fMRI scanned over the course of 3.5 years, and had their IQ predicted by the level of grey matter localization. This study was well-conducted, but studies of this sort frequently suffer from "double-dipping," where a single dataset is used both to identify the brain regions of interest and to develop a predictive model, which leads to overtraining of the model and an absence of real predictive power.[14]

The study authors avoided double-dipping by using a "leave-one-out" methodology, that involves building a predictive model for each of the n members of a sample based on data from the other n-1 members. This ensures that the model is independent of the subject whose IQ is being predicted, and resulted in a model capable of explaining 53% of the change in verbal IQ as a function of grey matter density in the left motor cortex. The study also observed the previously-reported phenomenon that a ranking of young subjects by IQ does not stay constant as the subjects age, which confounds any measurement of the efficacy of educational programs.[14]

These studies can be cross-validated by attempting to locate and assess patients with lesions or other damage in the identified brain region, and examining whether they exhibit functional deficits relative to the population. This methodology would be hindered by the lack of a "before" baseline measurement, however.

Phonological loop

The phonological loop is a component of working memory that stores a small set of words that can be maintained indefinitely if not distracted. The concept was proposed by the psychologists Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch to explain how phrases or sentences can be internalized and used to direct action. By using statistical parametric mapping to assess differences in cerebral blood flow between participants performing two different tasks, Paulescu et al.[15] were able to identify the storage of the phonological loop as in the supramarginal gyrii. Human subjects were first split into a control and experimental group. The control group was presented with letters in a language they did not understand, and non-linguistic visual diagrams. The experimental group was tasked with two activities: the first activity was to remember a string of letters, and was intended activate all elements of the phonological loop. The second activity asked participants to assess whether given phrases rhymed, and was intended to only activate certain sub-systems involved in vocalization, but specifically not the phonological storage.

By comparing the first experimental task to the second, as well as to the control group, the study authors observed that the brain region most significantly activated by the task requiring phonological storage was the supramarginal gyrii. This result was backed up by previous literature observations of functional deficits in patients with damage in this area.

Though this study was able to precisely localize a specific function anatomically and the methods of functional integration and imaging are of great value in determining the brain regions involved in certain information processing tasks, the low-level neural circuitry that gives rise to these phenomena remains mysterious.

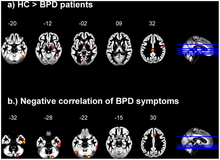

Psychiatric disorders

Although fMRI studies of schizophrenic and bipolar patients have yielded some insight into the changes in effective connectivity caused by these diseases,[16] a comprehensive understanding of the functional remodelling that occurs has not yet been achieved.

Montague et al.[17] note that the almost "unreasonable effectiveness of psychotropic medication" has somewhat stymied progress in this field, and advocate for a large-scale "computational phenotyping" of psychiatric patients. Neuroimaging studies of large numbers of these patients could yield brain activation markers for specific psychiatric illnesses, and also aid in the development of therapeutics and animal models. While a true baseline of brain function in psychiatric patients is near-impossible to obtain, reference values can still be measured by comparing images gathered from patients before and after treatment.

References

- Luca, M.; Beckmann, CF; De Stefano, N; Matthews, PM; Smith, SM (2006). "fMRI resting state networks define distinct modes of long-distance interactions in the human brain". NeuroImage. 29 (4): 1359–67. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.035. PMID 16260155.

- Hamalainen, M.; Hari, Riitta; Ilmoniemi, Risto J.; Knuutila, Jukka; Lounasmaa, Olli V. (1993). "Magnetoencephalography-theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain" (PDF). Rev. Mod. Phys. 65 (2): 413–97. Bibcode:1993RvMP...65..413H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.65.413.

- Logothetis, N. K. (2008). "What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI" (PDF). Nature. 453 (7197): 869–78. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..869L. doi:10.1038/nature06976. PMID 18548064.

- Bailey, DL (2005). Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Sciences. Elsevier. doi:10.1007/b136169. ISBN 978-1-84628-007-8. OCLC 209853466.

- Rosa, MJ; Daunizeau, J; Friston, KJ (2010). "EEG-fMRI integration: a critical review of biophysical modeling and data analysis approaches". Journal of Integrative Neuroscience. 9 (4): 453–76. doi:10.1142/S0219635210002512. PMID 21213414.

- Friston, K. (2002). "Functional integration and inference in the brain". Progress in Neurobiology. 68 (2): 113–43. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.4536. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00076-x. PMID 12450490.

- Friston, K.; Harrison, L; Penny, W (2003). "Dynamic causal modelling". NeuroImage. 19 (4): 1273–302. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00202-7. PMID 12948688.

- Buxton, RB; Wong, EC; Frank, LR (1998). "Dynamics of blood flow and oxygenation changes during brain activation: the balloon model". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 39 (6): 855–64. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910390602. PMID 9621908.

- Stephan, KE; Penny, WD; Moran, RJ; Den Ouden, HE; Daunizeau, J; Friston, KJ (2010). "Ten simple rules for dynamic causal modeling". NeuroImage. 49 (4): 3099–109. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.015. PMC 2825373. PMID 19914382.

- Daunizeau, J.; Preuschoff, K; Friston, K; Stephan, K (2011). Sporns, Olaf (ed.). "Optimizing experimental design for comparing models of brain function". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (11): e1002280. Bibcode:2011PLSCB...7E2280D. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002280. PMC 3219623. PMID 22125485.

- Friston, K.; Holmes, A. P.; Worsley, K. J.; Poline, J.-P.; Frith, C. D.; Frackowiak, R. S. J. (1995). "Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach" (PDF). Human Brain Mapping. 2 (4): 189–210. doi:10.1002/hbm.460020402.

- Ashburner, J.; Friston, KJ (2000). "Voxel-Based Morphometry-The Methods". NeuroImage. 11 (6): 805–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.114.9512. doi:10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. PMID 10860804.

- Urner, M.; Schwarzkopf, DS; Friston, K; Rees, G (2013). "Early visual learning induces long-lasting connectivity changes during rest in the human brain". NeuroImage. 77 (100): 148–56. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.050. PMC 3682182. PMID 23558105.

- Price, CJ; Ramsden, S; Hope, TM; Friston, KJ; Seghier, ML (2013). "Predicting IQ change from brain structure: a cross-validation study". Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 5 (100): 172–84. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2013.03.001. PMC 3682176. PMID 23567505.

- Paulesu E, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS (March 1993). "The neural correlates of the verbal component of working memory". Nature. 362 (6418): 342–5. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..342P. doi:10.1038/362342a0. PMID 8455719.

- Calhoun, V.; Sui, J; Kiehl, K; Turner, J; Allen, E; Pearlson, G (2011). "Exploring the psychosis functional connectome: aberrant intrinsic networks in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2 (75): 75. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00075. PMC 3254121. PMID 22291663.

- Montague, P.; Dolan, RJ; Friston, KJ; Dayan, P (2012). "Computational psychiatry". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 16 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.018. PMC 3556822. PMID 22177032.

Further reading

- Büchel, C. (2003). Virginia Ng; Gareth J. Barker; Talma Hendler (eds.). The Importance of Connectivity for Brain Function. Psychiatric neuroimaging. Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Psychiatric Neuroimaging, 29 September-1 October 2002, Chiavari, Italy --T.p. verso. Amsterdam; Washington, DC: IOS Press. pp. 55–59. ISBN 9781586033446. OCLC 52820961.

- Friston, Karl J. (2004). Kenneth Hugdahl; Richard J Davidson (eds.). Characterizing Functional Asymmetries with Brain Mapping. The asymmetrical brain. Bradford Books Series. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 161–186. ISBN 9780262083096. OCLC 645171270.

- Friston, K. J. (Karl J.) (2007). Statistical parametric mapping : the analysis of functional brain image. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-372560-8. OCLC 254457654.