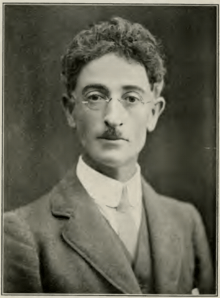

Frederick William FitzSimons

Frederick William FitzSimons (6 August 1870 Garvagh, Ireland – 25 March 1951 Grahamstown),[1] was an Irish-born South African naturalist, noted as a herpetologist for his research on snakes and their venom, and on the commercial production of anti-venom.

Frederick William FitzSimons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 August 1870 Garvaghy, Ireland |

| Died | 25 March 1951 (aged 80) |

| Spouse(s) | Patricia H. Russell |

| Children | Vivian Frederick Maynard FitzSimons, Desmond Charles FitzSimons |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Herpetology |

FitzSimons emigrated to South Africa in 1881 and was educated in Natal and then returned to Ireland to study medicine and surgery for three years. However, he returned to Pietermaritzburg in 1895 without qualifying.

Curator of museums

FitzSimons was appointed curator of the Pietermaritzburg Museum in 1897 from where he transferred to the Natal Government Museum. In 1906 he moved once more to the Port Elizabeth Museum as director. In 1918 he founded Africa's first snake-park there, which was also the world's second.[2]

Interests in archaeology

Of great interest at the time, FitzSimons' 1913 examination of and report on hominid skull fragments originating from Boskop near Potchefstroom,[3] led to a flurry of speculation:

Twelve years ago there was discovered in the Transvaal a remarkable human skull of apparently great antiquity. Fitzsimons, of Port Elizabeth Museum, first described it as perhaps allied to the Neanderthal but without the large supra-orbital ridges. The skull was next sent to Cape Town on loan, where it was described at some length by Haughton as allied to the Cromagnon man. Shortly afterwards I examined it in Port Elizabeth, and, impressed by the huge size of the brain, the great thickness of the bone—in places 15 mm.—and certain remarkable features in the jaw, I thought it worthy of specific rank and named it "Homo capensis". Now the specimen has been sent to the British Museum for further examination, and there has just appeared a paper by Pycraft which will be regarded as the official British Museum report.

Subsequently, many similar skulls were unearthed by prominent palaeontologists of the day, including Robert Broom, Alexander Galloway, William Pycraft, Sidney Haughton, Raymond Dart, and others. The current view is that Boskop Man was not a species, but a variation of anatomically modern humans; there are well-studied skulls from Boskop, South Africa, as well as from Skuhl, Qazeh, Fish Hoek, Border Cave, Brno, Tuinplaas, and other locations.

FitzSimons' anthropological work also included studies of the coastal Bushmen or Strandlopers who were ultimately displaced by the Khoikhoi.

Herpetologist

FitzSimons' interest in snakes is probably what he is best remembered for, and when he established a snake park at the museum for visitors, it was also to study snakes and snake-bites. From this he became a published authority on South African snakes and their venoms and he patented a (now outdated) first-aid and serum treatment kit.[1]

His son Vivian Frederick Maynard FitzSimons (1901-1975) became director of the Transvaal Museum in 1947, had a particular interest in South African reptiles, and helped establish the Namib Desert Research Association.[5] His other son, Desmond Charles FitzSimons, established the Durban Snake Park on the Golden Mile, Durban.[1]

Legacy

Frederick William FitzSimons is commemorated in the scientific name of a subspecies of lizard, Tetradactylus africanus fitzsimonsi.[6]

Publications

- FitzSimons, Frederick William (1923). "The Bushmen at the Zuurberg". South African Journal of Science. 20: 501–503.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- FitzSimons, F. W. (1915). "Palæolithic Man in South Africa". Nature. 95 (2388): 615–616. doi:10.1038/095615c0. ISSN 0028-0836.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- FitzSimons, F.W. (1912). "Snakes of South Africa; Their Venom and the treatment of Snake Bite". 547pp

References

- Biography of Frederick William FitzSimons at the S2A3 Biographical Database of Southern African Science

- Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Volume 4.

- FitzSimons 1915.

- Broom R (1925). "The Boskop Skull". Nature. 116 (2929): 897. doi:10.1038/116897a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Grobler, Elda (2006). Collections management practices at the Transvaal Museum, 1913-1964 : Anthropological, Archaeological and Historical (Thesis). University of Pretoria. hdl:2263/24550.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("FitzSimons, F. W.", p. 91).