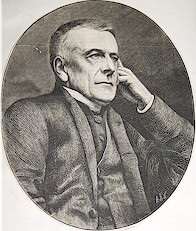

Frederick Oakeley

Frederick Oakeley (5 September 1802 – 30 January 1880)[1] was an English Roman Catholic convert, priest, and author. He was ordained in the Church of England in 1828 and in 1845 converted to Catholicism, becoming Canon of Westminster in 1852.[2] He is best known for his translation of the Christmas carol Adeste Fideles (O Come All Ye Faithful) from Latin into English.[3]

Early life

The youngest child of Sir Charles Oakeley, 1st Baronet, he was born on 5 September 1802 at the Abbey House, Shrewsbury. In 1810 his family moved to the bishop's palace at Lichfield. Poor health prevented his leaving home for school, but in his fifteenth year he was sent to Charles Sumner for tuition. In June 1820 he matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford; he gained a second class in litreæ humaniores in 1824. After graduating B.A. he won the chancellor's Latin and English prize essays in 1825 and 1827 respectively, and the Ellerton theological prize, also in 1827.[4]

In 1827 he was ordained, and was elected to a chaplain fellowship at Balliol College. In 1830 he became tutor and catechetical lecturer at Balliol, and a prebendary of Lichfield on Bishop Henry Ryder's appointment. In 1831 he was select preacher, and in 1835 one of the public examiners to the university. The Bishop of London, Charles Blomfield; appointed him Whitehall preacher in 1837, when he resigned his tutorship at Balliol, but he retained his fellowship.[4]

Tractarian

During his residence at Balliol as chaplain-fellow (from 1827) Oakeley became connected with the tractarian movement. Partly under the influence of William George Ward, he had grown dissatisfied with evangelicalism, and in the preface to his first volume of Whitehall Sermons (1837) he avowed himself a member of the new Oxford school. In 1839 he became incumbent of Margaret Chapel, the predecessor of All Saints, Margaret Street, and Oxford ceased to be his home.[4]

During the six years that Oakeley passed as minister of Margaret Chapel (1839–45), he became, according to a friend's description, the "introducer of that form of worship which is now called ritualism". He was supported by prominent men, among the friends of Margaret Chapel being Mr. Serjeant Bellasis, Mr. Beresford-Hope, and William Gladstone. According to an account by Mr. Wakeling the innovations of Oakeley's time were limited to the proper furnishing of the altar, a good standard of preaching but little more in the way of ritual.[5]

The year 1845 was a turning-point in Oakeley's life. As a fellow of Balliol he had joined in the election to a fellowship there of his lifelong friend and former pupil Archibald Campbell Tait, the future primate; but Tait had signed, with three others, the first protest against Tract XC. The furore over this last Tract led Oakeley, like Ward, to despair of his church and university; and in two pamphlets, published separately at the time both in London and Oxford, he asserted that he held, "as distinct from teaching, all Roman doctrine". For this avowal he was cited before the court of arches by the Bishop of London. His license was withdrawn, and he was suspended from all clerical duty in the province of Canterbury until he had "retracted his errors" (July 1845).[4]

Catholic

In September 1845 Oakeley joined John Henry Newman's community at Littlemore, and on 29 October was received into the Roman communion in the little chapel in St. Clement's over Magdalen Bridge. On 31 October he was confirmed at Birmingham by Nicholas Wiseman. From January 1846 to August 1848 he was a theological student in the seminary of the London district, St. Edmund's College, Ware. In the summer of 1848 he joined the staff of St. George's, Southwark; on 22 January 1850 he took charge of St. John's, Islington; in 1852, on the establishment of the new hierarchy under Wiseman as cardinal-archbishop, he was created a canon of the Westminster diocese, and held this office for nearly thirty years, till his death at the end of January 1880,[4] aged 77.

Works

Oakeley published 42 works. Before his conversion were:[4]

- Whitehall Chapel Sermons (1837)

- Laudes Diurnæ; the Psalter and Canticles in the Morning and Evening Services, set and pointed to the Gregorian Tones by Richard Redhead, with a preface by Oakeley on antiphonal chanting, 1843

Also a number of articles contributed to the British Critic.

After his conversion he brought out many books in support of Catholicism, including:[4]

- The Ceremonies of the Mass (1855) a standard work at Rome, where it was translated into Italian by Lorenzo Santarelli, and published by authority;

- The Church of the Bible (1857)

- The Order and Ceremonial of the Most Holy and Adorable Sacrifice of the Mass: Explained in a Dialogue Between a Priest and a Catechumen (1859)

- Lyra Liturgica (1865)

- Historical Notes on the Tractarian Movement (1865)

- The Priest to the Mission (1871)

- Catholic Worship: A Manual of Popular Instruction on the Ceremonies and Devotions of the Church (1872)

- The Voice of Creation (1876)

He was a constant contributor to the Dublin Review and The Month. To Cardinal Manning's Essays on Religious Subjects (1865) he contributed The Position of a Catholic Minority in a non-Catholic Country. The last article he wrote was one in Time (March 1880), on Personal Recollections of Oxford from 1820 to 1845 (reprinted in Lilian M. Quiller-Couch's Reminiscences of Oxford, 1892, Oxf. Hist. Soc.) His Youthful Martyrs of Rome, a verse drama in five acts (1856), was adapted from Cardinal Wiseman's Fabiola.[4]

See also

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Frederick Oakeley |

- Adeste Fideles on Wikipedia

- Adeste Fideles, the original Latin on Wikisource

- O come all ye faithful, Oakeley's translation on Wikisource

References

- Frederick Oakeley's family tree

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Frederick Oakeley 1802–1880".

- Beazley 1895.

- Kelway, Clifton (1915) The Story of the Catholic Revival. London: Cope & Fenwick; pp. 70-71

- Attribution

![]()

External links

- Works by Frederick Oakeley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)