Frederick Hammersley

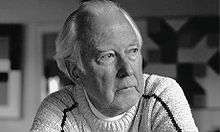

Frederick Hammersley (January 5, 1919 – May 31, 2009)[1] was an American abstract painter. His participation in the 1959 Four Abstract Classicists exhibit secured his place in art history.

Frederick Hammersley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 5, 1919 |

| Died | May 31, 2009 (aged 90) |

| Education | Chouinard Art Institute École des Beaux-Arts Jepson Art Institute |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Hard-edge painting |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship (1973) National Endowment for the Arts (1975, 1977) |

Early years

Frederick Hammersley was born in Salt Lake City, Utah.[2] His father, a Department of the Interior employee, moved the family to Blackfoot, Idaho[3] and eventually to San Francisco, where the young Hammersley first took art lessons.[1] His studies later took him back to Idaho, at Idaho State University in Pocatello from 1936 to 1938 and then to Los Angeles for the Chouinard Art Institute starting in 1940.[1][2] There he studied everything from figure painting to lettering[4] and his instructors included Rico Lebrun.[5] His artistic training was interrupted by a stint in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and Infantry as a graphic designer.[4] His World War II service in England, Germany, and France was from 1942 to 1946.[2][6] Fortuitously, he was stationed in Paris near the end of his service, and he took the opportunity to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in 1945. During this period, Hammersley met Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Constantin Brâncuși, visited their studios,[1][6] and made sketches.[3]

Hammersley returned to the U.S. and resumed his studies at Chouinard (1946), with financial assistance from the G.I. Bill.[1] A year later, he continued his art education at the experimental Jepson Art Institute for another three years.[1][2][6]

Work

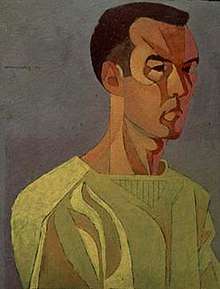

Oil on CB panel; 23 x 18 in.

He began a teaching career at Jepson in 1948, staying until 1951. Subsequent teaching positions included Pomona College (1953–62), Pasadena Art Museum (1956–61), Chouinard (1964–68), and University of New Mexico (1968–71).[1][2][6]

Hammersley first gained widespread acclaim when his paintings were featured in the landmark Four Abstract Classicists exhibit, which also showcased the work of Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin, and Lorser Feitelson.[1] This 1959 exhibit was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and curated by Jules Langsner, who, with Peter Selz, coined the term "hard-edge painting" to describe the work of these artists. The exhibit, which traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and Queen's University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, was praised for its presentation of cool abstractions which were very different from the emotional ones of the established abstract expressionist movement.[7]

He moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1968 and took a teaching position at the University of New Mexico; he stopped teaching in 1971 so that he could concentrate full-time on painting.[8] In 1973 he was honored with a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in painting,[8][9] and he received National Endowment for the Arts fellowships in 1975 and 1977.[3][9]

Hammersley wrote in an exhibition catalog, "hard-edge is often very hard to take, coming to it cold – or, even to the practiced eye".[7][10] He expanded his repertoire beyond hard-edge, dividing his art into three categories: "hunches", "geometrics", and "organics".[7]

"Hunch" paintings, produced from 1953 to 1959, start by laying down an initial shape. Other shapes are successively added, and the whole evolves in unplanned ways. Hammersley explained: "My painting begins with a hunch, no plan, no theory, just a feeling to make a shape. That shape dictates what and where the next will go, and so on..."[3] The final canvas may be suggestive of a still-life or a landscape, although still quite abstract. Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Miles wrote that "they show Hammersley to have been, from the start, as keen a student of Modernist style as he was of color and composition."[4]

"Geometrics" are orchestrated compositions of sharp geometric forms, painted from 1959 to 1964, and from 1965 to the mid-'90s. While more rigidly composed than Hunches, they still retain a degree of playfulness. A gridded canvas may have sections divided by diagonals or arcs. The triangles, squares, and other geometric shapes combine to form interlocking relationships to each other, creating a rhythmic composition with interchangeable positive and negative space.[4]

"Organics" consist of freely curving shapes inspired by the natural world. These works, produced in 1964 and from 1982 into the 2000s, also contain interlocking shapes, but, as Miles wrote, they "are more evocative and suggestive, with elements seeming to probe and penetrate, embrace and envelop one another. Particularly effective is the combination of hard breaks between colors from one shape to the next with gradations between colors within a shape. In Comes Out Eden, #8 (1994), shapes seem to fade in and out, to merge, dematerialize or change states – to behave like chameleons and run hot and cold."[4]

In reviewing Visual Puns and Hard-Edge Poems: Works by Frederick Hammersley, a 2000 retrospective, Los Angeles Times critic Leah Ollman wrote that he

... proved himself more a soft-hearted humanist than a hard-edged purist. ...

Hammersley takes several steps toward making his work more accessible, less aloof. For one, he uses titles as invitations in, catalysts to closer looking. ... [P]unning, free-associative title ideas ... mimic the formal dynamics enacted by the shapes... They joust, contradict, tease, echo and conspire.

Another savvy and refreshing move Hammersley makes is to counter the clean, impersonal precision of hard-edge painting with the amusing presence of his own personality, his own hand. ... Most brilliantly of all, he contains each of his works within wooden frames that he makes by hand... Artificially distressed and self-consciously homey, the frames offset the neat balances of the images within. They nudge the works into a stylistic no-man's-land, which is all the richer for its internal contradictions and resistance to cut-and-dried uniformity.

By reinforcing a connection to the familiar world of touch, the frames also scuttle the notion that abstraction belongs to a rarefied superstratum of experience. Hammersley consistently keeps his feet on the ground and his gaze on the world around him, a world where abstractions are a functional part of the mix.[10]

Art critic David Pagel commented that the complex arrangements of colors and geometric shapes in some paintings featured in a 2002 show made Hammersley "look like a Baroque artist in Minimalist clothing.[11]

In addition to paintings, Hammersley also produced photographs, computer-generated art, prints and drawings.[8][10]

Hammersley died on May 31, 2009 at his home in Albuquerque.[6]

Selected exhibitions

A small sample of Hammersley's exhibitions:

Solo exhibitions

- 1962 California Palace of the Legion of Honor

- 1963 La Jolla Art Museum, La Jolla, CA

- 1965 Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA

- 1999–2000 Visual Puns and Hard-Edge Poems: Works by Frederick Hammersley, Museum of Fine Arts (Santa Fe), University of New Mexico, Laguna Beach Art Museum

- 2007 Hunches, Geometrics, Organics: Paintings by Frederick Hammersley, Pomona College Museum of Art

- 2011 Organic and Geometric, Ameringer, McEnery, Yohe, New York, NY

Group exhibitions

- 1959-60 Four Abstract Classicists, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, England; Queen's University, Belfast, Northern Ireland; Western Association of Art Museums

- 1965 The Responsive Eye, Museum of Modern Art[8]

- 1977 35th Corcoran Biennial[8]

- 1994-96 Still Working, Corcoran Gallery of Art, The Chicago Cultural Center, The New School for Social Research, The Virginia Beach Center for the Arts, The Fischer Art Gallery at U.S.C., The Portland Museum of Art

- 2007-2009 Birth of the Cool, Orange County Museum of Art, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Oakland Museum of California, The Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

Collections

Hammersley's work is in many prominent collections including:[2][5][6][9]

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery

- Albuquerque Museum

- Butler Institute of American Art

- Corcoran Gallery of Art

- Fogg Museum

- High Museum of Art

- The Huntington[12]

- La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- New Mexico Museum of Art[13]

- Oakland Museum

- Orange County Museum of Art

- Roswell Museum and Art Center

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- Santa Barbara Museum of Art

References

- Masters, Christopher (June 13, 2009). "Obituary: Frederick Hammersley". The Guardian. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Frederick Hammersley". LA Louver. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Frederick Hammersley". Orange County Museum of Art. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Miles, Christopher (March 12, 2007). "Ever true to forms". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Abstract Painter Frederick Hammersley Dead at 90". Art Ltd Magazine. Jul 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- Fairfield, Douglas (June 6, 2009). "Frederick Hammersley, 1919-2009: Artist known as vanguard of abstraction". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- Muchnic, Suzanne (June 6, 2009). "Frederick Hammersley dies at 90; acclaimed painter". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Hammersley, Frederick". The New York Times. June 14, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Frederick Hammersley". Charlotte Jackson Fine Art. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- Ollman, Leah (February 9, 2000). "A Hammersley Retrospective, With the Edges Softened". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- Pagel, David (January 18, 2002). "Frederick Hammersley, From Abstract to Inventive Clarity". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Press Release – Huntington Acquires Works by Pioneering Minimalist Tony Smith". The Huntington. December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Frederick Hammersley". New Mexico Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

External links

- Frederick Hammersley at L.A. Louver, with biography, articles, and many images organized by decade

- Archive containing various articles about Frederick Hammersley

- Frederick Hammersley papers Detailed description of the Frederick Hammersley papers at the Archives of American Art.

- Frederick Interview of Frederick Hammersley, January 2003. Center for Oral History Research, UCLA Library Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Frederick Hammersley sketchbooks, prints, notes, and working materials, 1948-1980. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no. 2013.M.33. The sketchbooks, notebooks and working materials provide meticulous technical details regarding Hammersley's methodology and the formal experimentation that preceded many of his paintings.