Fred Sargeant

Frédéric André Sargeant (born July 29, 1948)[1] is a French-American gay rights activist. He is a veteran of the 1969 Stonewall riots and was a co-founder and organizer of the first Gay Pride march and celebration.

Fred Sargeant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Frédéric André Sargeant July 29, 1948 Fontainebleu, France |

| Nationality | American and French (dual citizenship) |

| Occupation | Police officer (retired) |

| Known for | Veteran of the Stonewall riots and co-proposer and organizer of the first annual Gay Pride March |

| Website | fredsargeant |

Early life

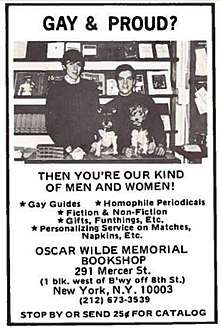

Sargeant was born in Fontainebleu, France, to an American G.I. father and a French mother.[1] He grew up in Connecticut[2] and moved to New York City at age nineteen.[3] There, he met and began dating Craig Rodwell, who had recently opened what was then the country's only gay bookstore, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in Greenwich Village. The bookshop was a gathering place for young gay activists, and soon Sargeant was managing the store and had become an active member of the Homophile Youth Movement (HYMN), which operated out of it.[2]

Stonewall riots

After 1 a.m.[4] on Saturday, June 28, 1969, Sargeant and Rodwell were returning from dinner at a friend's home and passed the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar and club owned by a member of the Genovese crime family. They saw a crowd of about 75 people gathered outside the Inn and a police car in front, and were told the club had been raided. As police emerged from inside the Stonewall leading a customer, someone began throwing coins at the officers and others joined in throwing objects and yelling insults, eventually forcing the police to retreat back into the building and call for reinforcements.[2] A full-scale riot broke out between the responding Tactical Patrol Force and the crowd that lasted for several hours, with Sargeant and Rodwell staying until the sun came up.[5]

In a radio interview that he gave to WBAI's New Symposium II days after the riot, Sargeant was asked what had set the crowd off and replied:

The kids felt that some of the other kids were being kept inside and being beaten up by the police. I don't know whether it really happened that way or not, but the rumor spread.[6]

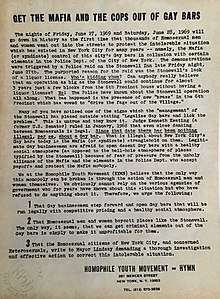

At dawn, the couple went back to their apartment, where Rodwell began writing the first of many leaflets calling for the gay community to seize the moment and stand up to the corrupt police and the mafia who controlled their neighborhoods.[7] He and Sargeant, aided by a group of volunteers, distributed about 5,000 copies[2] around the city on Sunday, after returning to the Stonewall again for a second night of rioting on Saturday evening.[8]

The headline on that first leaflet read "Get the Mafia and the Cops Out of Gay Bars" and began "The nights of Friday, June 27, 1969 and Saturday, June 28, 1969, will go down in history as the first time that thousands of homosexual men and women went out into the streets to protest the intolerable situation which has existed in New York City for many years."[9]

First Gay Pride march

Martha Shelley of the lesbian civil rights group Daughters of Bilitis had first suggested a protest march be planned in commemoration of the uprising at a special meeting of the Mattachine Society in the days following the riots.[7] As a member of Mattachine, Craig Rodwell had participated in July 4 'Annual Reminders' for gay rights at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. In an effort to make gay integration into society and the workforce seem non-threatening, Mattachine's Frank Kameny insisted on conservative dress and behavior at the protests: women were required to wear skirts and men suits, and no displays of affection were allowed between participants. At the Annual Reminder that was held just a week after the Stonewall riots began, Rodwell and other young activists balked at these restrictions, having come to the conclusion that more aggressive action was needed to achieve civil rights for gay people.[10]

Five months after the Stonewall riots, in November 1969, the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) convened in Philadelphia.[11] At the conference, Ellen Broidy and Linda Rhodes of the lesbian activist group Lavender Menace joined Rodwell and Sargeant in proposing the following resolution:

That the Annual Reminder, in order to be more relevant, reach a greater number of people, and encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged—that of our fundamental human rights—be moved both in time and location. We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called CHRISTOPHER STREET LIBERATION DAY. No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.[12]

Most of the preparation work was done by Sargeant, GLF members Michael Brown and Marty Nixon and Mattachine Society member Foster Gunnison Jr., who acted as treasurer.[13] They utilized the bookshop's mailing list to gather support and participants for the march and negotiated the details with over a dozen different gay advocacy groups including Lavender Menace and the Gay Activists Alliance.[2]

On the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, now considered the first NYC Pride March,[2] began with a few hundred participants in front of the Stonewall Inn. By the time it reached Sheep's Meadow in Central Park 50 blocks later, the marchers numbered in the thousands.[10]

Sargeant marched at the front of the parade and as the only person there with a bullhorn,[14] led the official chant: "Say it loud, gay is proud". He wrote in an article for The Village Voice in 2010:

At one point, I climbed onto the base of a light pole and looked back. I was astonished; we stretched out as far as I could see, thousands of us. There were no floats, no music, no boys in briefs. The cops turned their backs on us to convey their disdain, but the masses of people kept carrying signs and banners, chanting and waving to surprised onlookers[15]

Social media controversy

In 2020, Sargeant made controversial comments on Twitter regarding transgender people, some of which garnered additional attention after author JK Rowling "liked" a tweet he had sent.[16] He voiced support for the LGB Alliance,[17] an organization which advocates the positions that sexual attraction is based on biological sex, gender is a social construct,[18] and transgender rights should not be included within the common umbrella of LGBT activism. This view has been criticized as transphobic.[19] In April 2020, Sargeant tweeted "I prefer to call @AllianceLGB a pro-LGB human rights organization under attack from homophobic trans rights groups. It's time to remove the T from same-sex advocacy groups. Trans has nothing to do with us and we owe them nothing."[17] Citing this tweet, LGBTQ Nation subsequently referred to Sargeant as an "anti-transgender activist".[20]

Personal life

In 1971, Sargeant left New York and returned to Connecticut, where several years later, he decided to become a police officer: "I wanted to see if I could make a difference, and having seen the situation at Stonewall and how the NYPD handled that, I thought I could do it differently. Stonewall wasn't the only riot I saw. I'd been caught up in riots in the Village before and watched what the police did."[7] He went on to attain the rank of lieutenant with the Stamford Police Department before retiring.[21]

Sargeant appeared in the 2011 documentary film, Stonewall Uprising.[22] He wrote the foreword to the 2019 book The Stonewall Riots: Coming Out in the Streets by Gayle E. Pitman.[23] In 2014, Sargeant was honored as one of the founders of Gay Pride at the 44th annual New York City Pride March, where he once again marched at the front of the parade with a bullhorn.[24] He resides in Vermont[24] with his husband, whom he married in 2010.[7]

Citations

- Armati 2019

- Fitzsimons 2019

- Pitman 2019, p. vii

- Duberman 1994, p. 192

- Duberman 1994, p. 200

- Carter 2005, p. 149

- PBS 2010

- Duberman 1994, pp. 201–206

- Pitman 2019, p. 105

- Fitzsimons 2018

- Duberman 1994, p. 226

- Kohler 2019

- Carter 2005, p. 247

- Pitman 2019, p. 148

- Sargeant 2010

- Fistonich 2020

- Sargeant 2020

- Swerling 2019

- Petter 2019

- Bollinger 2020

- Sargeant 2009

- Sanders 2011

- Library of Congress

- Lindholm 2014

General sources

- Armati, Lucas (June 2019). "Les gays se rebellent a Stonewall" (PDF). Causette. Paris: Causette Media. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Bollinger, Alex (May 18, 2020). ""Harry Potter" author J.K. Rowling continues support for extreme anti-transgender rhetoric". LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved June 28, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, David. (2005). Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-3123-4269-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duberman, Martin. (1994). Stonewall. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-4522-7206-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fistonich, Matt (May 26, 2020). "JK Rowling under fire again for anti-trans controversy". gaynation. Retrieved June 28, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzsimons, Tim (October 5, 2018). "LGBTQ History Month: The road to America's first gay pride march". NBC News. Retrieved May 2, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzsimons, Tim (June 3, 2019). "#Pride 50: Fred Sargeant - Co-organizer of first NYC Pride March". NBC News. Retrieved April 29, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kohler, Will (May 5, 2019). "Forgotten Gay Heroes - Craig Rodwell: The Father of PRIDE". Back2Stonewall. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- Library of Congress. "Library of Congress Catalog Record for The Stonewall Riots: coming out in the streets". LC Catalog. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Lindholm, Jane (June 26, 2014). "Vermonter to be Honored at New York's Gay Pride Parade". Vermont Public Radio. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- PBS (2010). "Who was at Stonewall?". American Experience. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Petter, Olivia (October 24, 2019). "LGB Alliance group faces criticism for being transphobic". The Independent. Retrieved July 1, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pitman, Gayle E.. (2019). The Stonewall Riots: Coming Out in the Streets. New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-1-4197-3720-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanders, Kate (producer) (2011). Stonewall Uprising Interviews: Interview with Fred Sargeant (videotape). American Experience. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Sargeant, Fred (June 22, 2010). "1970: A First-Person Account of the First Gay Pride March". The Village Voice. Retrieved April 25, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sargeant, Fred (June 25, 2009). "Anger Management". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sargeant, Fred (April 8, 2020). "8 April 2020". Retrieved June 28, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swerling, Gabriella (October 23, 2019). "Trans dispute prompts new gay faction to break with Stonewall". The Telegraph. Retrieved June 28, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)